Also by Anne Roiphe

NONFICTION

Epilogue

Water from the Well: Sarah, Rebekah, Rachel and Leah

Married: A Fine Predicament

1185 Park Avenue: A Memoir

For Rabbit, with Love and Squalor

A Mothers Eye: Motherhood and Feminism

Fruitful: A Memoir of Modern Motherhood

A Season for Healing: Reflections on the Holocaust

Your Childs Mind: The Complete Book of Infant and Child Mental Health Care (with Dr. Herman Roiphe)

Generations Without Memory: A Jewish Journey Through Christian America

FICTION

An Imperfect Lens

Secrets of the City

The Pursuit of Happiness

If You Knew Me

Lovingkindness

Torch Song

Long Division

Up the Sandbox

Digging Out

Copyright 2011 by Anne Roiphe

Foreword copyright 2011 Katie Roiphe

Out of concern for the privacy of individuals depicted here, the author has changed the names of certain of those individuals as well as any potentially identifying descriptive details concerning them. The dates are as accurate as the authors memory will allow, which means they are imperfect.

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Nan A. Talese/Doubleday, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.nanatalese.com

Doubleday is a registered trademark of Random House, Inc.

Nan A. Talese and the colophon are trademarks of Random House, Inc.

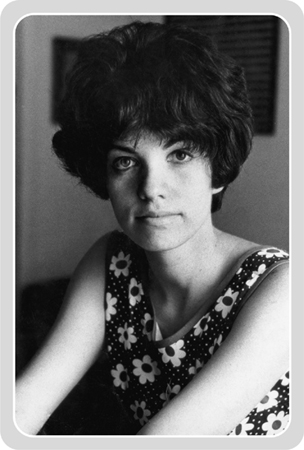

Frontispiece photo by Jonathan Bain

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Roiphe, Anne Richardson, 1935

Art and madness : a memoir of lust without reason / Anne Roiphe.

1st ed.

p. cm.

1. Roiphe, Anne Richardson, 1935 2. Women authors, American

20th centuryBiography. I. Title.

PS3568.O53Z46 2010

813.54dc22

[B] 2010028051

eISBN: 978-0-385-53165-8

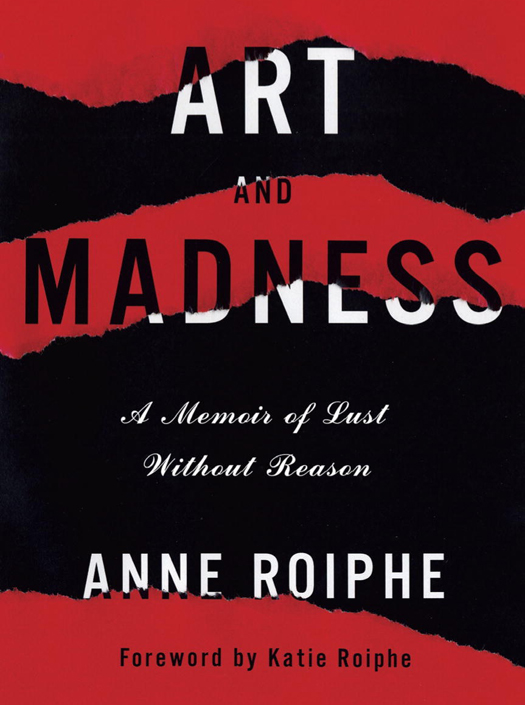

Jacket design by Emily Mahon

v3.1

For Dr. Herman Roiphe

Contents

Foreword

by Katie Roiphe

There is a photograph of my mother on the back jacket of her first novel, her black hair cropped close, huge kohl-rimmed eyes, a daisy-print minidress, a cigarette dangling from her hand. She is very young and very beautiful and, one senses, the tiniest bit uncertain in this new role as author. The caption reads: Anne Richardson is an active member of New Yorks young set. There are several aspects of this book jacket that are foreign to me: the name, the cigarette (she did not, in fact, know how to inhale), the young set. Who was my mother in her late twenties?

These were lost years. My mother, who has written comprehensively about every single period of her life, had never touched these years. She was one of the girls draped across the sofa at parties with Ed Doctorow, George Plimpton, Roy Lichtenstein, Terry Southern, Doc Humes, Jack Gelber, Norman Mailer, Peter Matthiessen, Larry Rivers, William Styron, and Arthur Miller. Decades later, when I would go to George Plimptons house for Paris Review parties, they took place in the same brownstone by the river. Plimpton said to me once, Those were wilder days when your mother was here. But what happened during those years? She wouldnt say. Do I ask you what you did in your twenties? was, I think, what she answered.

In those days, my mother was divorced from a brilliant, unsettled playwright and had a young child. She was living alone in an apartment at Eighty-sixth and Park Avenue, furnished with cheap rattan furniture, and had a black-and-white rabbit named Alouette, who was allowed to roam free through the apartment and ate the bindings off her French paperbacks.

In a sense, this book is the record of an idea as it moves through a life: the idea is the supreme and consuming importance of art. In her twenties my mother glorifies and reveres the artist in a way that is lost to us; a way that belongs to a world when book jackets said things like Anne Richardson is an active member of New Yorks young set. The male artists and writers she knew were tremendously charismatic, seductive, and women, vast swaths of them apparently, were seduced. But my mother also witnessed the other side of the artistic endeavor, the dangerous, searing narcissistic regard that these men had for themselves: the cheating, the violence, the drugs and drink. And by the time she reaches her thirties and forties, she begins to feel differently: she is by this time a writer herself, and she approaches her work as a craft, in a deliberate, workmanlike way. She writes notes for her novels as she is shopping for cereal in the grocery store. She treats her work with all the romanticism of a factory worker off for a day on the assembly line. Gone the sense of the divine, gone the idea that any sacrifice is worth making for the art; and this book charts the slow and painful and interesting evolution of that change.

Recently, on a winter afternoon, I went with my mother to see a documentary on Doc Humes, the iconic novelist who had helped found The Paris Review with George Plimpton in Paris. I was lost in the appeal of their world, the drinks at sidewalk cafs, the stylish manic energy, the bookish glamour of it all. But I could sense next to me in the darkness some sort of opposing view. The Doc in the movie was lovable, quirky, magnetic, larger than life; but his daughter who had made the film hadnt captured the pain he lived in and conjured around him; she hadnt caught the viciousness of his physical attacks on his wife. I understood that my mother had known Doc Humes, but in exactly what capacity she hadnt told me.

Not long ago, I came across a letter my mother had written to Bernard Malamud, who would come to our yellow-shingled house in Nantucket for summers. My love for you as a reader for a writer is as strong as any I have ever felt, she wrote. This line leaped out at me. How could your love for someone as a reader be as strong as any you ever felt? Somehow reading this now, remembering those summers in our yellow house, when my sister and I were sent out because Bern needed quiet to write, this reverence seems excessive, exotic. What did it mean, this serious, near-mystical devotion to writers, to the words on the page? Was there a time when people cared this much, when their intimacies were mingled to this extent with books?

Elizabeth Hardwick, herself married to a difficult poet, Robert Lowell, wrote about the women who surrounded the charismatic poets and writers of the period in an essay on Dylan Thomas. The young ladies she describes could easily have included my mother.

So powerful and beguiling was his imagethe image of a self-destroying, dying young poet of genius, that he aroused the most sacrificial longings in women. He had lost his looks, he was disorganized to a degree beyond belief, he had a wife and children in genuine need, and young ladies felt that they had fallen in love with him. They fought over him; they nursed him while he retched and suffered and had delirium; they stayed up all night with him, and went to their jobs the next morning. One girl bought cowboy suits for his children. Enormous mental, moral and physical adjustments were necessary to those who would be the companions of this restless, frantic man. The girls were up to itit was not a hardship but a privilege