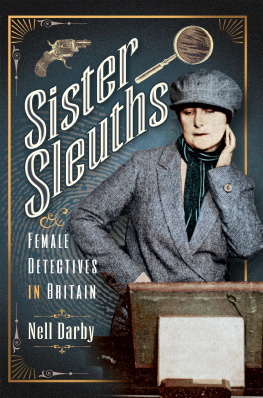

For my Dad, who introduced me to detective stories,

and for all the women who have fought for their

place and their right to protect and defend

citizens for nearly two centuries.

A NOTE ON TERMS

Although police officer has been the gender-neutral term for members of a police department for several decades, policewoman was the common term used from the earliest years of womens efforts to break into careers in law enforcement. Indeed, policewoman originally designated a specific and different role from that of the policeman. That role has changed too, but policewoman is still widely used, despite varying degrees of acceptance by officers and varying interpretations of the terms traditional connotations. My use of policewoman is not meant as a political statement or to indicate a stance on womens role in policing but simply as a means of clarity and continuity.

CHAPTER ONE

Detecting Women

W ITH HIGH HEELS CLICKING across the hardwood floors, the diminutive woman from Chicago strode into the headquarters of the New York City police. It was 1922. Few respectable women would enter such a place alone, let alone one wearing a fashionable Paris gown, a feathered hat atop her brown bob, glistening pearls, and lace stockings.

But Alice Clement was no ordinary woman.

Unaware ofor simply not caring aboutthe commotion her presence caused, Clement walked straight into the office of Commissioner Carleton Simon and announced, Ive come to take Stella Myers back to Chicago.

The commissioner gasped, Shes desperate!

Stella Myers was no ordinary crook. The dark-haired thief had outwitted policemen and eluded capture in several states.

Unfazed by Simons shocked expression, the well-dressed woman withdrew a set of handcuffs, ankle bracelets, and a wicked looking gun from her handbag.

Ive come prepared.

Holding up her handcuffs, Clement stated calmly, These go on her and we dont sleep until Ive locked her up in Chicago. True to her word, Clement delivered Myers to her Chicago cell.

Alice Clement was hailed as Chicagos female Sherlock Holmes, known for her skills in detection as well as for clearing the city of fortune-tellers, capturing shoplifters, foiling pickpockets, and rescuing girls from the clutches of prostitution. Her uncanny ability to remember faces and her flair for masqueradea different disguise every dayallowed her to rack up one thousand arrests in a single year. She was bold and sassy, unafraid to take on any masher, con artist, or scalawag from the citys underworld.

Her headline-grabbing arrests and head-turning wardrobe made Clement seem like a character straight from Central Casting. But Alice Clement was not only real; she was also a detective sergeant first grade of the Chicago Police Department.

Clement entered the police force in 1913, riding the wave of media sensation that greeted the hiring of ten policewomen in Chicago. Born in Milwaukee to German immigrant parents in 1878, Clement was unafraid to stand up for herself. She advocated for womens rights and the repeal of Prohibition. She sued her first husband, Leonard Clement, for divorce on the grounds of desertion and intemperance at a time when women rarely initiatedor wonsuch dissolutions. Four years later, she married barber Albert L. Faubel in a secret ceremony performed by a female pastor.

Its not clear why the then thirty-five-year-old, five-foot-three Clement decided to join the force, but she relished the job. She made dramatic arrestsmade all the more so by her flamboyant dressand became the darling of reporters seeking sensational tales of corruption and vice for the morning papers. Dark-haired and attractive, Clement seemed to confound reporters, who couldnt believe she was old enough to have a daughter much less, a few years later, a granddaughter. Grandmother Good Detective read one headline.

She burnished her reputation in a high-profile crusade to root out fortune-tellers preying on the naive. Donning a different disguise every day, Clement had her fortune told more than five hundred times as she gathered evidence to shut down the trade. Hats are the most important, she explained, describing her method. Large and small, light and dark and of vivid hue, floppy brimmed and tailored, there is nothing that alters a womans appearance more than a change in headgear.

Clement also had no truck with flirts. When a man attempted to seduce her at a movie theater, she threatened to arrest him. He thought she was joking and continued his flirtations, but hers was no idle threat. Clement pulled out her blackjack and clubbed him over the head before yanking him out of the theater and dragging him down the street to the station house. When he appeared in court a few days later, the man confessed that he had been cured of flirting. Not every case went Clements way, though. The jury acquitted the man, winning the applause of the judge who was no great fan of Clement or her theatrics.

One person who did manage to outwit Clement was her own daughter, Ruth. Preventing hasty marriages fell under Clements duties, and she tracked down lovelorn young couples before they could reach the minister. The Chicago Daily Tribune called her the Nemesis of elopers for her success and familiarity with everyone involved in the business of matrimony in Chicago. None of this deterred twenty-year-old Ruth Clement, however, who hoped to marry Navy man Charles C. Marrow, even though her mother insisted they couldnt be married until Marrow finished his time in service in Florida. Ruth did not want to wait, and when Marrow came to visit, the two tied the knot at a ministers home without telling Clement. When Clement discovered a Mr. and Mrs. Charles C. Marrow registered at the Chicago hotel supposedly housing Marrow alone, she was furious and threatened to arrest her new son-in-law for flouting her wishes. Her anger cooled, however, and Clement soon welcomed the newlyweds into her home.

Between arrests and undercover operations, Clement wrote, produced, and starred in a movie called Dregs of the City, in 1920. She hoped her movie would deliver a moral message to the world and warn young girls of the pitfalls of a great city.

The film created a sensation, particularly after Chicagos movie censor board, which fell under the oversight of the police department, condemned the movie as immoral. The picture shall never be shown in Chicago. Its not even interesting, read the ruling.

When the cruise ship Eastland rolled over in the Chicago River on July 24, 1915, Clement splashed into the water to assist in the rescue of the pleasure boaters, presumably, given her record, wearing heels and a designer gown. More than eight hundred people would die that day, the greatest maritime disaster in Great Lakes history. For her services in the Eastland disaster, Clement received a gold coroners star from the Cook County coroner in a quiet ceremony in January of 1916.

Clements exploits and personality certainly drew attention, but any woman would: a female crime fighter made for good copy and eye-catching photos. Unaccustomed to seeing women wielding any kind of authority, the public found female officers an entertainingand sometimes ridiculouscuriosity.

That certainly held true for Loveday Brooke. A professional detective with the Lynch Court agency in London, Brooke was smart, confident, and bold. She earned the complete confidence of her boss, Ebenezer Dyer. To those who questioned Brookes detecting skills and fitness for the job, Dyer gruffly replied, I dont care two pence-halfpenny whether she is or is not a lady. I only know she is the most sensible and practical woman I ever met.