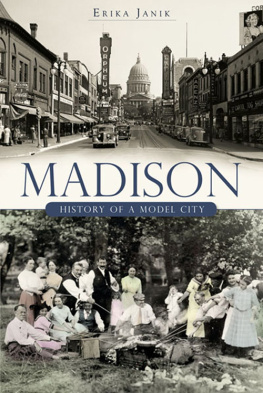

MADISON

Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2010 by Erika Janik

All rights reserved

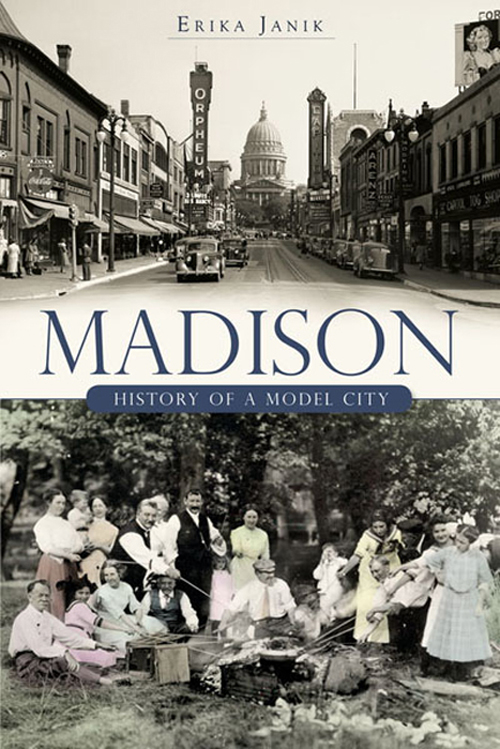

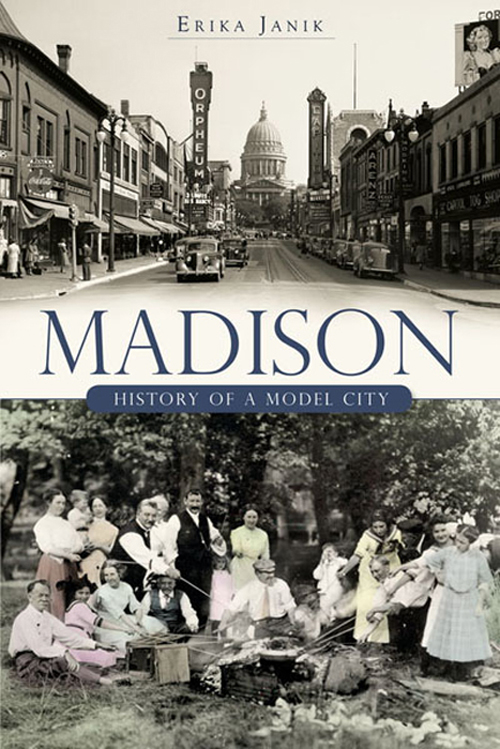

Front cover, top: State Street, 1939. Wisconsin Historical Society Image #3151. Bottom:

German-American wurst roast. Wisconsin Historical Society Image #1971.

Back cover, top: Lakeside House. Wisconsin Historical Society Image #25114. Bottom: Mansion

Hill Inn (formerly the Pierce House). Image by author.

First published 2010

e-book edition 2011

ISBN 978.1.61423.054.0

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Janik, Erika.

Madison : history of a model city / Erika Janik.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

print edition: ISBN 978-1-59629-121-8

1. Madison (Wis.)--History. 2. Madison (Wis.)--Social conditions. I. Title.

F589.M157J36 2010

977.583--dc22

2010033159

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

While writing itself is a solitary pursuit, the process of putting together a book is certainly not. Thanks to the Wisconsin Historical Society for its tremendous historical riches and resources, both human and archival. Thanks, too, to the many historians, authors, residents, journalists, leaders and others who cared enough about Madisons future to leave a rich and colorful record of its past. Any errors or omissions are mine.

My friends put up with me for months as I worked on this book, offering encouragement, support and long lunch breaks. Thank you for still wanting to be my friends. My parents helped me move to Madison many years ago and have waited patiently for my return to Redmond, Washington. Im sorry to tell you Im still here, and now Ive written a book about it. Thank you for understanding. Finally, and most especially, thanks to my husband, Matt, for his patience, good humor and generosity in listening to me talk history far more than any one person should have to bear. His constant support sees me through.

INTRODUCTION

Ebenezer Brigham left the first account of the land that would become Madison. Recalling his visit in 1828, he said, The site was at the time an open prairie, on which grew dwarf oaks, while thickets covered the lower grounds. He then predicted, with remarkable foresight, that the land might be perfect for the capital of a new state (Wisconsin belonged to the Michigan Territory at the time).

Oddly enough, Jefferson Davis also passed through Madison in 1829. The future president of the Confederate States of America had been sent to Wisconsin to help build Fort Winnebago in 1828. Davis and his company of soldiers passed through Madison looking for deserters. He later recalled the area as abundant in fish and waterfowl and noted that the Indians ate primarily corn and wild rice.

Madisons beauty and potential were not obvious to all early visitors, however. To the soldiers pursuing Black Hawk in the summer of 1832, Madison did not leave a good impression. If these lakes were anywhere else except in the country they are, wrote one, they would be considered among the wonders of the world. But the country they are situated in, is not fit for any civilized nation of people to inhabit.

Fortunately, the man who would play an integral role in Madisons future took the former view when he first saw the isthmus in May 1829. Judge James Duane Doty, traveling overland from Green Bay to Prairie du Chien, liked what he saw so much that he purchased the land and platted a grid of streets for a future capital city that he called Madison. He then successfully lobbied the legislature for its creation.

Less than a century later, landscape architect John Nolen would show Madison an aspirational vision of itself that would serve as a challenge for future generations. His 1911 report revealed a Madison that took full advantage of its natural assets, a place as pleasing to the eye as it was to live and work. With just a little effort, Nolen said, Madison could become a model city for the world.

From its very beginning, Madisons story is one of its residents striving to achieve its potential, to become the world-class city that many people believed in and desperately wanted it to be. Farsighted leaders like James Doty, Lucius Fairchild, John Olin and John Nolen played integral roles in molding and forming the Madison of today.

Surrounded by lakes and located on an isthmus, water and land have played an integral part in Madisons past and present. The land and its resources have allowed people to survive and thrive here for thousands of years, creating an inseparable bond between natural and human histories.

Madisons story, while unique, is also part of a larger American story of settlement, growth, immigration and change. The citys history reflects all that has happened here, from glacial retreats and Ho-Chunk villages to city parks, Earth Day marches and the rich intellectual legacy of the University of Wisconsin. This book attempts to tell that story for residents both new and old.

1

ANCIENT PEOPLES

The Ho-Chunk called them Tay-cho-per-ah, or Four Lakes. An 1832 American surveyor followed suit, labeling Madisons lakes numbers one through four. And so the lakes remained numerically named until 1854, when they finally received individual namesthough Madison retains its Four Lakes nickname even today.

Water both defined and constrained Madison. Set on a narrow isthmus between Lakes Mendota and Monona, Madison is surrounded by a network of lakes, marshes, streams and riversa visible marker of the regions glacial past.

Only fifteen thousand years ago, most of North America lay beneath colossal sheets of ice. These advancing and retreating glaciers formed the headlands of Cape Cod and the Finger Lakes in upstate New York. But nowhere is the glaciers mark more impressive than in Wisconsin, so much so that most of the recent glacial advances and retreats of the Laurentide glacier sheet have been given the name Wisconsin.

The last glacier to flow into Wisconsin came about twenty-five thousand years ago and covered about two-thirds of the state. The glaciers leading edge divided into two bulges, one headed toward Chicago and the other, known as the Green Bay lobe, headed toward Madison some fourteen to twenty thousand years ago. The flowing ice gouged and scraped the land, leaving ridges called moraines and elongated hills called drumlins, one of which the capitol building in Madison sits on today. Everywhere the glacier went, it profoundly transformed the land.

As the glacier receded, meltwater flowed from the glaciers southwestern edge, filling the space between the edge of the ice mass and the high ground to the west of Madison with water. The result was Glacial Lake Yahara.

The glacial lake covered more than twenty-six thousand acres and was more than 100 percent larger than current lakes Mendota, Monona and Wingra combined. With water levels around twelve feet above the current lake levels, Glacial Lake Yahara cut Madisons isthmus into a series of islands and peninsulas. Glacial Lake Yahara eventually broke through the glacial debris that had dammed the valley and led to its creation, causing the water levels to drop and the modern Yahara River to form, as well as lakes Mendota, Monona and Wingra. The retreat of the glacier also opened the land to settlement.

Next page