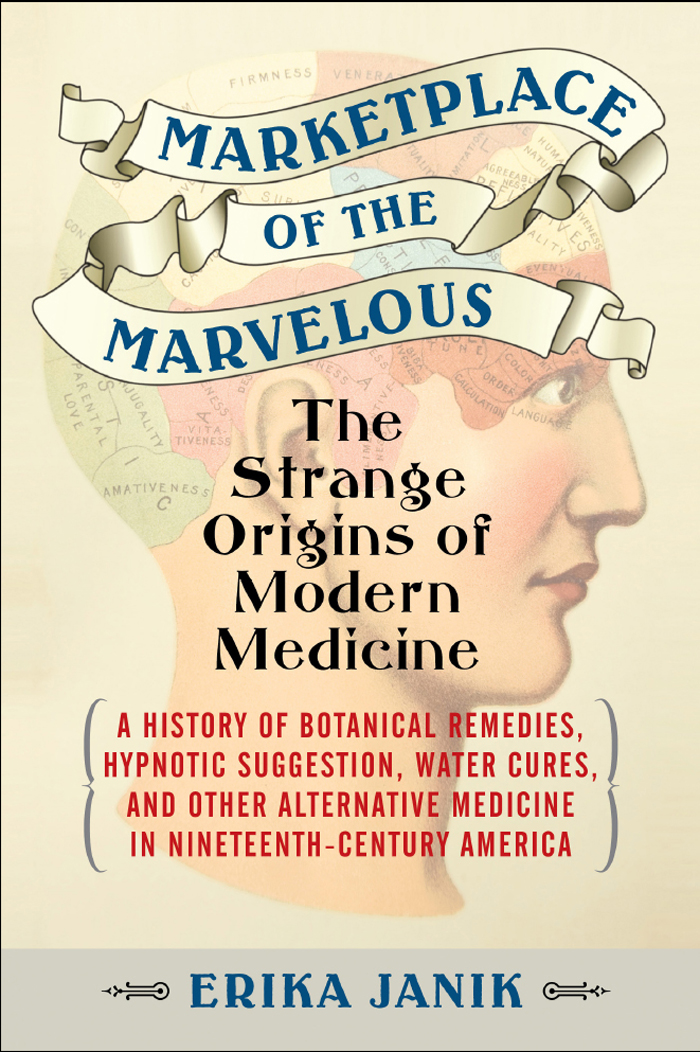

Erika Janik - Marketplace of the Marvelous: The Strange Origins of Modern Medicine

Here you can read online Erika Janik - Marketplace of the Marvelous: The Strange Origins of Modern Medicine full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2014, publisher: Beacon Press, genre: Science. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Marketplace of the Marvelous: The Strange Origins of Modern Medicine

- Author:

- Publisher:Beacon Press

- Genre:

- Year:2014

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

Marketplace of the Marvelous: The Strange Origins of Modern Medicine: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Marketplace of the Marvelous: The Strange Origins of Modern Medicine" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

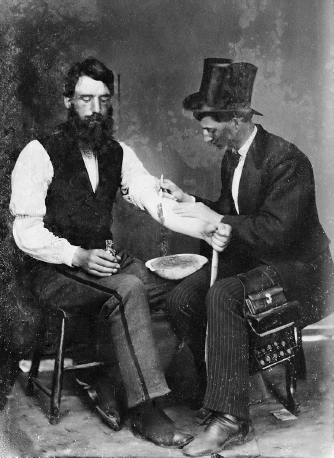

Despite rampant scientific innovation in nineteenth-century America, traditional medicine still adhered to ancient healing methods, subjecting patients to bleeding, blistering, and induced vomiting and sweating. Facing such horrors, many patients ran with open arms to burgeoning practices that promised new ways to cure their ills. Hydropaths offered cures using healing waters and tight wet-sheet wraps. Phineas Parkhurst Quimby experimented with magnets and tried to replace bad, diseased thoughts with good, healthy thoughts, while Daniel David Palmer reportedly restored a mans hearing by knocking on his vertebrae. Lorenzo and Lydia Fowler used their fingers to read their clients heads, claiming that the topography of ones skull could reveal the intricacies of ones character. Lydia Pinkham packaged her Vegetable Compound and made a famous family business from the homemade cure-all. And Samuel Thomson, rejecting traditional medicine, introduced a range of herbal remedies for a vast array of woes, supplemented by the curative powers of poetry.

Bizarre as these methods may seem, many are the precursors of todays notions of healthy living. We have the nineteenth-century practice of medical gymnastics to thank for todays emphasis on regular exercise, and hydropathys various water cures for the notion of regular bathing and the mantra to drink eight glasses of water a day. And much of the philosophy of health introduced by these alternative methods is reflected in todays patient-centered care and holistic medicine, which takes account of the body and spirit.

Moreover, these entrepreneurial alternative healers paved the way for women in medicine. Shunned by the traditionalists and eager for converts, many of the masters of these new fields embraced the training of women in their methods. Some women, like Pinkham, were able to break through the barriers to women working to become medical entrepreneurs themselves. In fact, next to teaching, medicine attracted more women than any other profession in the nineteenth century, the majority of them in irregular health systems.

These eccentric ideas didnt make it into modern medicine without a fight, of course. As these new healing methods grew in popularity, traditional doctors often viciously attacked them with cries of quackery and pressed legal authorities to arrest, fine, and jail irregulars for endangering public safety. Nonetheless, these alternative movements attracted widespread supportfrom everyday Americans and the famous alike, including Mark Twain, Louisa May Alcott, and General Ulysses S. Grantwith their messages of hope, self-help, and personal empowerment.

Though many of these medical fads faded, and most of their claims of magical cures were discredited by advances in medical science, a surprising number of the theories and ideas behind the quackery are staples in todays health industry. Janik tells the colorful stories of these quacks, whose oftentimes genuine wish to heal helped shape and influence modern medicine.

Erika Janik: author's other books

Who wrote Marketplace of the Marvelous: The Strange Origins of Modern Medicine? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.