Table of Contents

Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

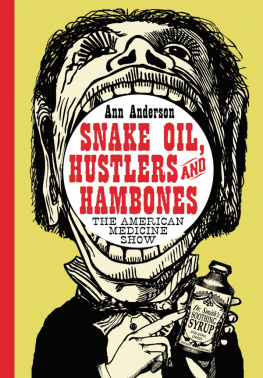

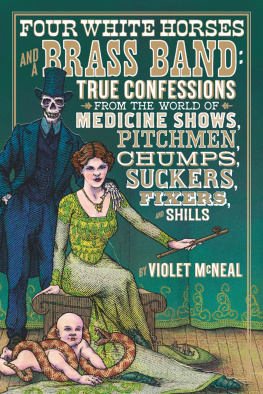

Anderson, Ann, 1951

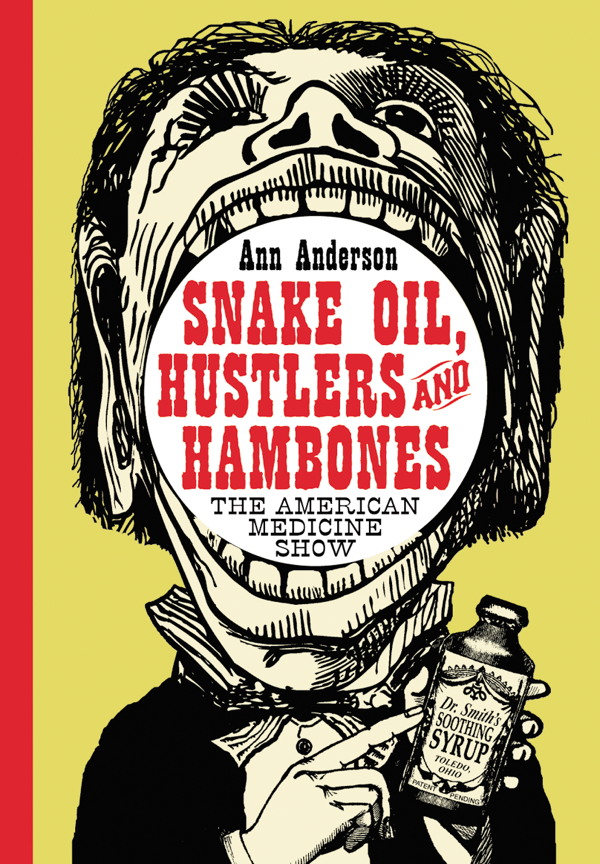

Snake oil, hustlers and hambones : the American medicine show / Ann Anderson ; foreword by Heinrich R. Falk.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-7864-2228-9

1. Quacks and quackeryUnited StatesHistory19th century. 2. Medicine showsUnited StatesHistory19th century. 3. HealersUnited StatesHistory19th century. 4. Patent medicinesUnited StatesHistory19th century. I. Title.

R730.A54 2005

615.8'56'09034dc21 00-30486

British Library cataloguing data are available

2000 Ann Anderson. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

To my mother

Foreword

Theatre studies have come a long way since Aristotle. For centuries theatre was treated as literature on a stage. The idea of theatre as something performed, with or without literary pretensions, did not fully emerge until the twentieth century. Even today, theatre as performance in the absence of a written text is frequently relegated to the margins of scholarly attention and interest.

Studies of popular theatre and entertainment often adopt one of two general approaches. There are popular studies, which present an entertaining story with scant attention to the underlying scholarship; and there are scholarly monographs, which often squeeze all that is popular out of the telling of the story. Popular studies lack substance; scholarly studies lack interest and excitement. Frequently neither approach to popular theatre contextualizes the phenomenon within its broader historical and social framework.

The following treatment of the medicine show in America combines careful scholarship with a presentation that reflects the interest and excitement inherent in this popular entertainment. Because the medicine showmen appropriated elements from many of the contemporary popular entertainments, including the circus, wild west shows, minstrel shows, and even vaudeville, this book examines the medicine show within the broader context of popular theatre as well as social history. Medical practices, commerce, and advertising are explored in relation to the history of the rise and eventual demise of the medicine show in America.

Snake Oil, Hustlers and Hambones reminds us that the entertainment we watch every night on television is simply the hook for the offers during the intervals to cure our real and imagined aches and painsthe sweet spoonful that tricks us into drinking the medicine down.

Heinrich R. Falk

Santa Barbara, CA

May 2000

1

Origins and Influences

How much is your health worth, Ladies and Gentlemen? Its priceless, isnt it? Well, my friends, one half-dollar is all it takes to put you in the pink. Thats right, Ladies and Gents, for fifty pennies, Natures True Remedy will succeed where doctors have failed. Only Nature can heal and I have Nature right here in this little bottle. My secret formula, from Gods own laboratory, the Earth itself, will cure rheumatism, cancer, diabetes, baldness, bad breath, and curvature of the spine.

At the turn of the twentieth century, such claptrap was heard on street corners all across America. The great American medicine show doc operated on the premise that people long to believe in a magic bullet that will cure their pains in an instant. He told his audiences what they wanted to hear, and they rewarded him with medicine purchases. His rapid-fire spiel was a theatrical mix of circus, wild west show, minstrelsy, vaudeville, and popular drama. Equal parts entertainment, sermon, and doctors house call, medicine shows were samplers of American popular theater in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Dog-and-pony shows, magic tricks, pie-eating contests, mediums, and menageries put audiences in a buying mood. Anything entertaining or attention-getting made its way onto the medicine show platform. In the history of marketing, medicine shows were the link between the medieval European mountebank who told stories and sold potions in the village square, and todays television commercial. The medicine show is now extinct, but its primary principle survives: Give the folks free entertainment and theyll buy anything youve got.

Before the advent of electronic media, the presentation of amusement and remedies to the North American populace was perforce a live event. From roughly 1800 to 1940, the medicine-show pitchman traversed the continent from end to end, promising health in a bottle. His cure-all was bogus, but his show delivered what it advertiseda diversion from the tedium of daily life. From one year to the next, he provided the only entertainment to be had for isolated village dwellers, farmers, miners, loggers, and oil-field workers.

Medicine showmen have existed all over the world and in every age, including ancient Egypt and classical Greece. The American traveling medicine show, however, was a unique theatrical phenomenon. A hybrid of popular culture and confidence game, the shows were as varied as the medicines and as brash and energetic as America itself.

Medieval Origins

The traditions of the American medicine show came from Europe and were invented some time during the Middle Ages (a.d. 6001350), when performing was discouraged. Before that, at the height of the Roman Empire and during its long decline, there was plenty of work for actors, singers, dancers, and jugglers. The demise of performing as a legal profession began in a.d. 410 when a barbarian army sacked Rome. Germanic tribes had their own kind of mimes and singers, but thought Roman theater effete and decadent. The new rulers of Rome allowed theater to continue only as a consolation to the vanquished.

In addition to barbarians, performers had another foe: the Christian Church had opposed the gladiatorial bloodbaths, animal massacres, and lewd pantomimes of the Romans for centuries. In a.d. 568, the church finally succeeded in banning theaters and circuses throughout Europe. In the face of constant opposition from church and state, performers sprang into action, collected whatever pay they could, and left town in a hurry.

One day an unknown entertainer had the bright idea to do tooth extractions as a part of his act, and the medicine show was born. This innovator and the other fleet-footed dancers, acrobats, and mimes who followed his lead started a line of performers that extended to the nineteenth-century American medicine showmen.

Italy

A performer who trafficked in potions and dentistry was known as a mountebank, which literally means he who jumps on a bench. Nowhere in Europe was the mountebank more prevalent than in Italy, and nowhere in that country was he a more common sight than in Venice. In fact, the term Venetian mountebank came to mean any mountebank.

The word mountebank is often used interchangeably with charlatan, from the Italian ciarlatano, or one who sells salves or other drugs in public places, pulls teeth and exhibits tricks of legerdemain.Charlatan later came to mean a chattering con artist, one who impersonates an educated man and knowingly sells fake medicine. (Some medicine sellers were sincere but misinformed, and some accidentally stumbled upon a potion that did sufferers some good. Still others knew a little about medicine and simply enjoyed showing off their learning in public. The difficulty for consumers, then and now, lies in identifying the phonies.)

Next page