In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Thank you for buying this ebook, published by Hachette Digital.

To receive special offers, bonus content, and news about our latest ebooks and apps, sign up for our newsletters.

Sign Up

Or visit us at hachettebookgroup.com/newsletters

For more about this book and author, visit Bookish.com.

Copyright 2013 by Josh Ruxin

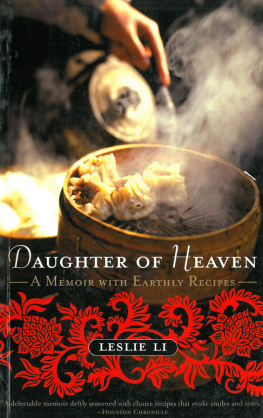

Cover design by Ploy Siripant

Cover copyright 2013 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

All rights reserved. In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

littlebrown.com

twitter.com/littlebrown

facebook.com/littlebrownandcompany

First ebook edition: November 2013

Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

Photographs by Josh and Alissa Ruxin, unless otherwise noted

Title page photograph by Ian Christmann

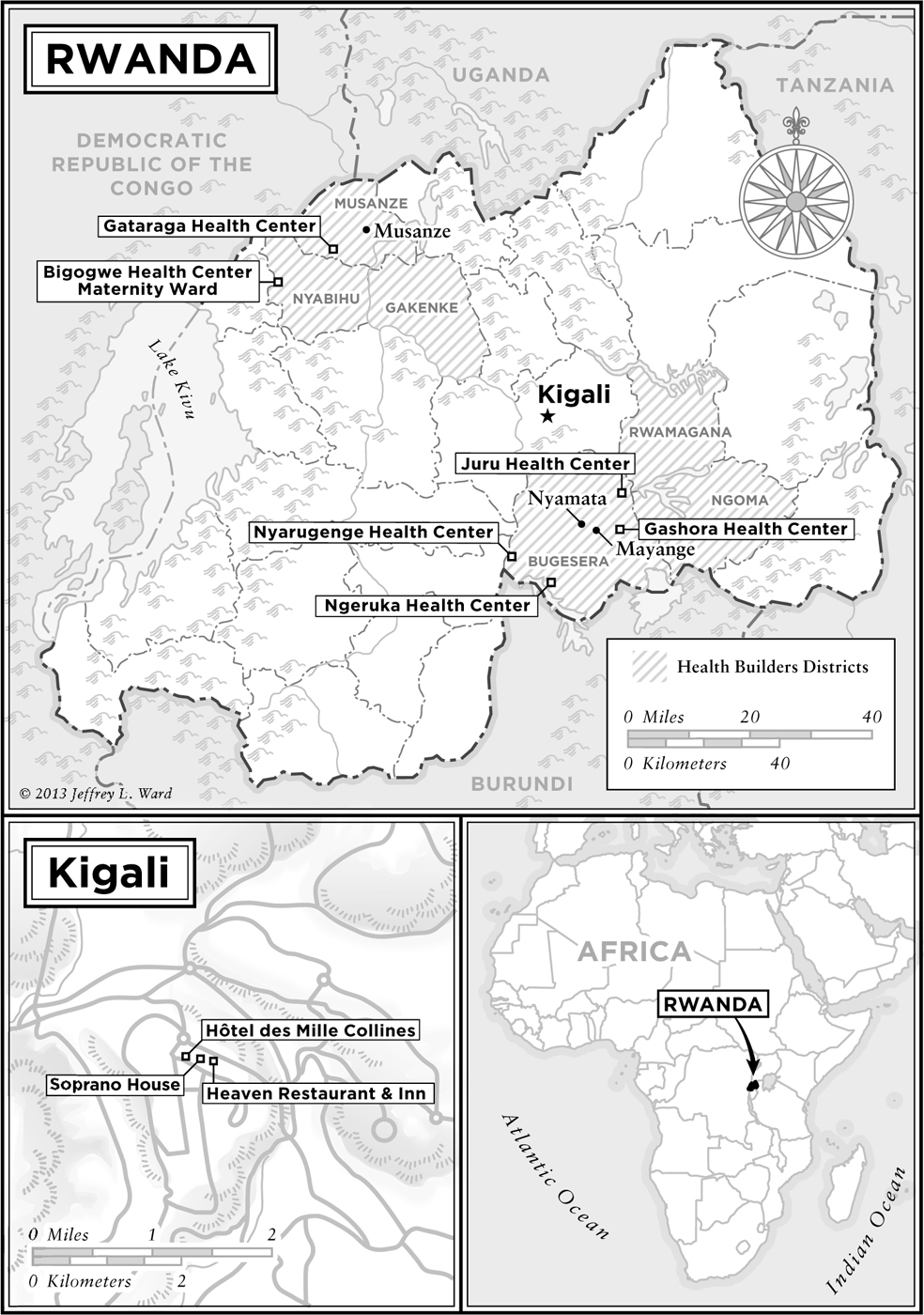

Map by Jeffrey L. Ward

ISBN 978-0-316-23289-0

For Alissa

T his is not a book about the Rwandan genocide, nor is it a book about politics. It is not a cookbook (exactly). Its a book about our marriage, our adventures together in the Heart of Darkness, and about Heaven, our hillside restaurant and bar in Rwanda, where, from the outdoor dining deck, there is a very good evening view of the end of poverty.

O ur plane drifts up over the Atlantic at dusk. We watch a film or two, then doze off. The sun comes up as we float down to Brussels. A cup of coffee there, then we rise over the morning Alps, and then the blue Mediterranean, and finally the torn, brown edge of Africa. There is a thick brown haze belowa midday sandstorm in the Sahara. It takes time to cross the Sahara, as it is about the size of the United States. Africa is big enough to hold all of the United States, including Alaska, plus all of Mexico, all of China, India, France, Spain, Germany, Italy, Greece, Turkey, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and the United Kingdom. Even then, youd have enough land left over for two States of Texasbut Africa has enough trouble. When economists describe Africa as the next China, or the next New World, you have to keep in mind how impossibly big it is, but also how filled it is with energetic, ambitious young people and unmeasured resources. It is too violent, yes, but so was North America once.

In a few hours we are high above the pain and beauty of Darfur, where horrific atrocities are still playing out, and then over oil-rich and therefore troubled South Sudan. Then over Uganda with its booming economy and new constructionits traffic jams are glowing jewelry below, as night has fallen. Beyond that, only a few slash-and-burn fires below relieve the incredible darkness in the heart of Africa. Finally we slide down along the swampy, reed-lined shores of Lake Victoria, which is as large as Lake Michigan, and into Rwanda. The nation of Rwanda is two-thirds the size of Switzerland, or about the size of Massachusetts, but round like a fist and tucked just under the Equator.

On approach to the little nations capital, Kigali, we fly over the spot where the plane carrying the presidents of Rwanda and Burundi was shot down on April 6, 1994, triggering perhaps the cruelest one hundred days in human history. Roughly a million men, women, and children were killed, mostly by machete. Then, east of Rwanda, across the Congo borderthe darkest spot on the continentmillions more died in the years following 1994, and fighting continues there even now, driven by a lack of government and an excess of militias, gold, diamonds, oil, and memories of murder. It is the nation next door and a constant worry.

But we do not go quite that far. As our plane lands and finally rolls to a stop, four men push a stairway to the door. We hundred people pull down our bags, fumble for business cards for seatmates, relocate passports and yellow fever vaccination cards, and shuffle out. Most passengers seem to be Rwandans or other Africans, coming home or on business. Maybe a quarter of the people are Europeans and Americans, some no doubt coming to work with a charity or church group. A few look like tourists: middle-agers on their way to the misty ridges of the volcanoes in the north of Rwanda, where they will sit among the mountain gorillas like the fellow primates they are. As we exit, there are some very awake people, young and old, whose eyes seem ravenous for every new sight around them and whose smiles are as fixed as if they had just taken a hit of somethingAfrica is indeed an altered state for those fully open to it.

If you arrived before dark, you would see a green hilly country with farming terraces cut into every slopeeven terraced up the sides of the volcanoes, and terraced down into the bowls of them. Rwanda is the most crowded country in Africa, and therefore the most farmed. But one usually arrives late, as it is a long way from anywhere.

Arriving at nine oclock in the evening seems like midnight. It feels good to walk around on the tarmac after such a lengthy flight. The airplane is massive in the darkness above you, and the miracle of flight seems more real than in a Western airport, where you slip out through a deep corridor, never really seeing the big bird for what it is, and never having that moment to just look up and marvel at it for bringing you such a long way, so quickly and safely. Travelers and explorers of the past had to suffer years of canoe paddling, diseases, and murderous jungle trekking to get heremost not arriving this far inland until well into the twentieth century.

You have used the assembled knowledge of Western civilization to get here more easily, though you are tired. You stand in the cool African air, hear the caws of night birds, smell the signature scent of Africaa blend of the days burning of leaves swept from the streets by ten thousand women with straw brooms and gunny sacks, plus the tropical sweetness of flowers and the dust and faint pungency of the faraway open sewers of poverty. There might be a bread bakery in the distance, is how it seems.

Next page