First published in Great Britain in 2013 by

Pen & Sword Military

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Philip Matyszak 2013

HARDBACK ISBN: 978-1-84884-787-3

PDF ISBN: 978-1-47383-104-9

EPUB ISBN: 978-1-47382-988-6

PRC ISBN: 978-1-47383-046-2

The right of Philip Matyszak to be identified as the Author of this

Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright,

Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British

Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical

including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and

retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in Ehrhardt by

Mac Style, Driffield, East Yorkshire

Printed and bound in the UK by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon,

CRO 4YY

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword

Aviation, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military, Wharncliffe

Local History, Pen and Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics,

Leo Cooper, The Praetorian Press, Remember When, Seaforth

Publishing and Frontline Publishing.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

To the memory of Krystyna Dzuirdzik 19382012

Acknowledgements

This book required detailed information from people familiar with areas of Spain and Portugal where I have not been myself. So thanks to those who have been my eyes on the ground particularly Felix Paulinski, Fernando Quesada Sanz, Director. Dpto. de Arqueologa, Universidad Autnoma de Madrid, Beatriz Ezquerra Lebrn, Conservadora del Museo de Teruel, and Alberto Prez of Desperto Ferro magazine. Thanks also go to Jean-Luc Fraud, the re-enactor who posed for the pictures of a legionary of the 1st century BC and Jasper Oorthuys of Ancient Warfare magazine, who stepped in to help at the last minute. The nature of the work required discussing what if? scenarios with a number of ancient historians, all of whom participated enthusiastically in the discussion and considerably influenced the final text. Finally, Id like to thank those people who, having bought previous books, have taken the time to write and tell me what they particularly enjoyed about them. Hearing from readers always makes my day.

List of Illustrations

Maps

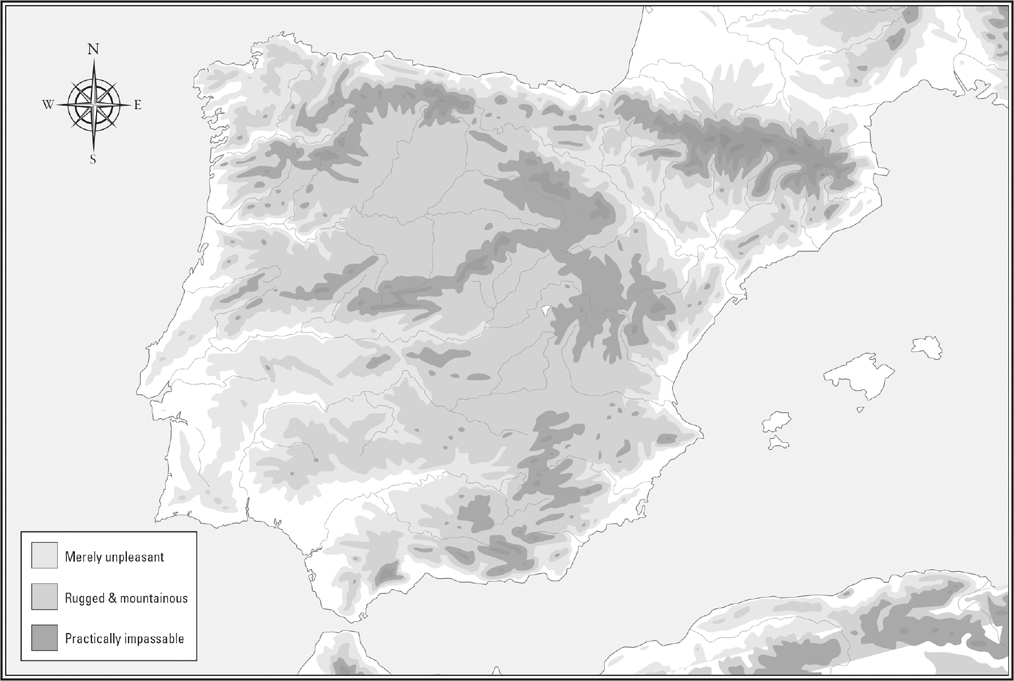

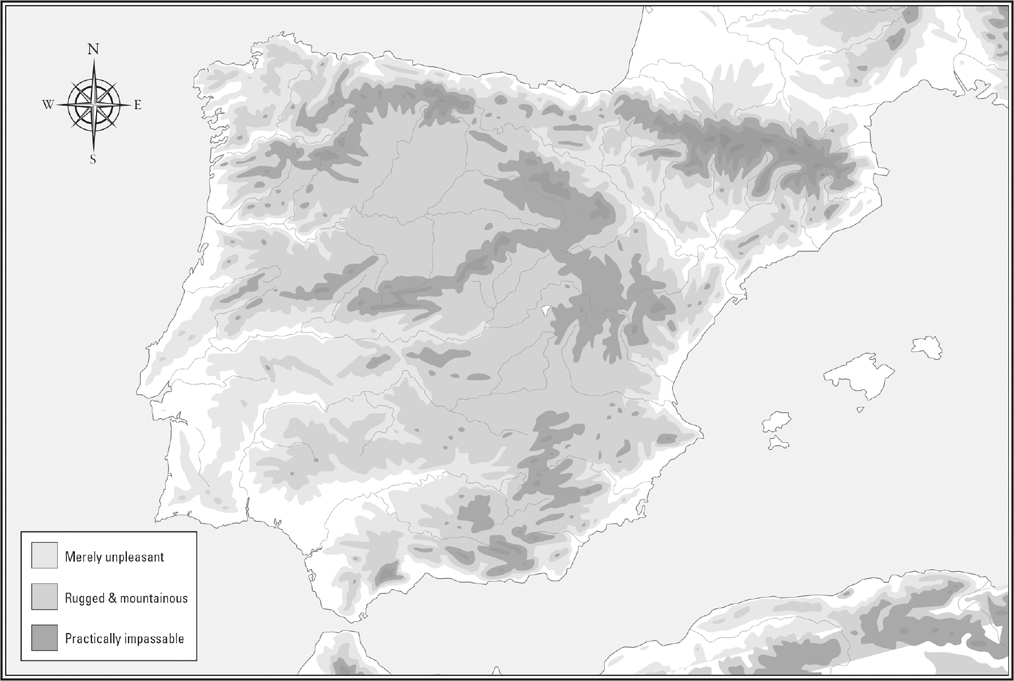

Iberia from a campaigning point of view.

The cities and rivers of Iberia.

Iberias major ethnic groups.

Introduction

T his is not a history of the Sertorian war in Iberia of 8271 BC, because that history is lost. We have a good record of the Jugurthan war in Africa just a generation before, and a generation later we are spoiled rotten by having an account of the Gallic war written for us by one of the leading protagonists Julius Caesar himself. Yet between these wars two entire provinces fell from the control of the central government of Rome and remained for almost a decade under the rule of a charismatic military genius and precisely what happened is largely a mystery.

It is not that the war was considered unimportant. The historian Sallust the same man who brought us detailed reporting of the Jugurthan war covered the war in Iberia in considerable depth. Individual actions, speeches and an organized chronology explained the war to the Roman public, and if anyone wanted a second opinion, they had only to turn to Livys magisterial Ab urbe condita. The history of Rome from the foundation covered the war in Hispania at the same time as it described contemporary events and wars all around the Mediterranean. And if this were not enough, the character of Sertorius inspired the biographer Plutarch to write the story of his life.

Yet this detailed mass of information is largely gone, blown apart by the winds of time. Of the war as described by Sallust all that remains are a few fragmentary pieces of text, usually preserved because some later grammarian used the fragment to illustrate a quirk of Sallustian style. Of Livy there remains only his Epitome a brutally abbreviated edition of the text which crams entire chapters into a few short sentences. The Epitome has been neatly described as Roman history on Twitter and Livys tweets on the Sertorian war are few and seldom even 140 characters long. Yet today, starved of other information, the researcher pounces on them gratefully.

This leaves us with Plutarch, and without Plutarch one would have to abandon the entire project. Plutarchs Life of Sertorius survived, and survived almost entirely intact. But the biography of a general is not the history of a war, especially if our biographer is the un-military Plutarch. Plutarch tells us of the mood of his hero (and for Plutarch, Sertorius is definitely a hero) at times when we would rather like to know things like army numbers and deployments. And because Plutarch keeps the spotlight unwaveringly on his protagonist we are left to discover elsewhere that (for example) a lot of the war was fought by a highly competent second-in-command whom Plutarch does not even mention.

Fortunately for later historians the Sertorian war was a very big deal at the time, and it reverberated through Roman history to an extent where we can pick up the echoes. Valerius Maximus wrote on the Doings and Sayings of Famous Men, and some of those who fought in the Sertorian war were famous indeed. So from Valerius Maximus we get anecdotes and snippets of a personal nature. The Sertorian war was also a masterclass exercise in generalship on both sides as the high attrition rate of lesser generals demonstrates. Therefore when a later commander called Frontinus collected a book of anecdotes illuminating the art of generalship, a good many of his exemplars were taken from the Sertorian war.

Even at the end (chronologically speaking) of the Roman empire, with almost a thousand years of history to relate, writers such as Florus and Orosius dedicated several pages to Sertorius; another historian, Appian, gave the war a cursory and occasionally inaccurate treatment as a lead-in to his main topic: the struggle between Caesar and Pompey.

Despite the existence of such brief and fragmentary accounts, it is fair to say that unless further documentation comes to light, the full story of Sertorius and his war is lost beyond retelling. So this book is not a history. It is a reconstruction. Using Plutarchs account as a scaffold, the other fragments and anecdotes can be carefully fitted around his narrative. The result is a sort of sudoku played with scraps of evidence. The trick is to place each fragment within a timeline to create a narrative. Each fragment must be both internally consistent with other fragments and with what is known of wider contemporary Roman history. So, for example, when Cicero gives an offhand mention that a character was in Rome in a particular year, we can place the first fragment describing that characters activity in Iberia soon after that date, and so tentatively date a fragment which says only it was late in the season.

Next page