All rights reserved.

CROWN and the Crown colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

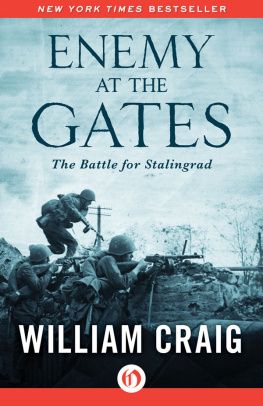

American casualty in Europe, 1944. [National Archives]

PROLOGUE

THE GRAVES

EUROPE, OCTOBER 1989

THEY LAY BENEATH PERFECT rows of white graves that lined lush green lawns. He knew where they were buried. He had their names. Finding all of them meant walking back and forth, all across the graveyard, through avenues of thousands of white crosses. But he could manage the strain. His heart had given him problems for years, yet he still had the strength, the will, to search for his men. They had died near here, at Anzio, the bloodiest piece of ground occupied by American and British forces during World War II. Seventy-two thousand men lost in allkilled, wounded, sent insane, blown to shreds, missing, or captured, now a mere statistic in a history book.

The men he had commanded had achieved something of lasting greatness, something of permanence. They had defeated barbarism. He had seen it. He had been there, poisoned and heartbroken but somehow blessed, or rather damned, with the strength to fight on, to beat Hitlers most violent men.

Often he had questioned what kept his men going. The American Army was on the attack all the time in Europe. He had kept thinking: Why do they go? It was hard to explain why his men had not hesitated. Many times he had said: Lets go! Every time, they had gone. Now that he was back in Europe, he marveled once more at the American spirit, as he called it, that had kept them advancing toward death or at best debilitating injury. It was this spirit that had mattered so much when the odds had been even.

The American soldiers under his command had performed magnificently. He wanted to pay his respects to some of those who had fallen. That was why he was back. There had been no time during combat to stand over them and grieve, no time to say how he felt, to show his love other than by trying his best to keep them alive. At that, he had failed, over and over, and over again.

Never give up. That was what had counted most. He had never given up, not once in his entire life. He had fought since he could rememberto eat, to stay alive, to overcome everything a vengeful God could throw at him. He had survived, somehow, perhaps through grit and rage, perhaps because God took the good first and left the rotten until last.

He had never been afraid of God or any man. Fear had never thrown him off balance, but he had felt great anxiety, mostly about what was going to happen to his men. Thankfully, he had always been able to think and act fast. In fact, he had functioned extraordinarily well in combat, remaining for the most part calm and focused. He had some of the fighting Irish in him plus a lot of anger. It was in his blood. His great grandfather had fought at the Alamo.

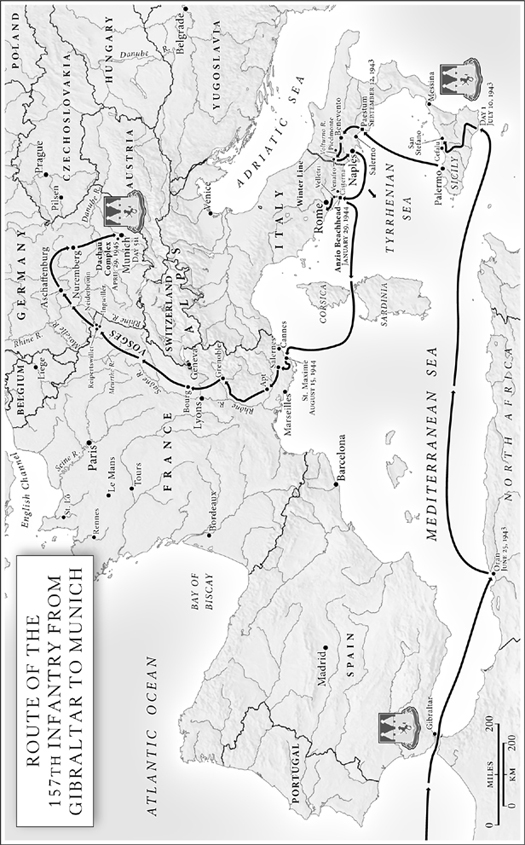

The graves of his men stretched across Europe, over two thousand miles. They had died in Sicily, in France, at the dark heart of Nazi Germany. There had been several hundred killed under his command, half of them buried in Europe. Near a crossing over the fast-flowing Moselle, he looked for Sergeant Vanderpool and Lieutenant Railsbacks final resting places. Railsback had looked like a high school valedictorian with his confident, easy smile and neatly cropped hair. He had been a hell of an officer, like Sparks at his age. As for Vanderpoolhe should never have died. He should have ignored the fact that he wanted to stay with his brother and pulled him off the line, but he had left it too late.

On the German border, near a small village, he traipsed along the ridge where he had been beaten just that one time, where in snow and ice the SS had humiliated him. His mens foxholes were still there as well as their spent cartridges. He had never gotten over their loss. How could anyone recover from losing so many men? Thirty platoon leaders and six hundred warriors who had never hesitated to carry out his every command.

Then it was on into the dark forests where you could get lost after a hundred yards without a compass, a place of primeval fears, to the border of Germany and the Siegfried Line with its famous dragons teeth, now decomposing concrete and rusted iron; across the swirling Rhine to a city on the banks of the Main River where a grateful mayor and townspeople honored him and left him beaming with pride; south toward the Alps and a pretty town where he pointedly reminded the good burghers that the German government had authorized the building of a center for the study of the Holocaust. Why hadnt it been built? Much as they might want to forget, future generations should not.

He had never been able to forget that day. He could still picture the girl lying on top of all the bodies. It was as if she and others were looking at him with reproach, asking: What took you so long?