ROBERT SERVICE

THE LAST

OF THE TSARS

Nicholas II and the Russian Revolution

MACMILLAN

To Lara, Dylan, Joely and Keira

Contents

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgements

My thanks and love go to my wife, Adele Biagi, who read the complete draft of the book. The last of the Russian tsars is a new interest for me, and Adeles comments were, as always, of inestimable value. I could not have written these chapters without her help. Others who examined the draft were Semion Lyandres, Simon Sebag Montefiore and Ian Thatcher. Semion shared his expertise about the February 1917 Revolution; Sebag advised on the whole Romanov dynasty as well as on the national question in Russia; Ian provided helpful counsel on general questions about interpretation of evidence. I am indebted to them them for their willingness to take time away from their own projects.

I am also grateful to Katya Andreyev for help with Russian Orthodox Church nomenclature; to Richard Clogg for advice about the origins of Russian studies of Byzantine history; to Paul Gregory for tips on books to read on Siberian history; to Lena Katz for explaining the linguistic history of Jews in Russia; to Norman Naimark for clarifying aspects of Jewish history in the revolutionary period; to Robert Sells for his help at an early stage of the research with Romanov medical questions; to Nick Walshaw for sharing his family newspaper clippings on British naval action in the Black Sea; and to Andrei Zorin for our discussions of Russian imperial law and traditions about abdication and succession. Linda Bernard, Lyalya Kharitonova, Carol Leadenham, Anatole Shmelev and Lora Soroka at the Hoover Institution Archives assisted unstintingly whenever I had queries; I should also like to thank the Hoover Institution Librarys Maria Quinonez and Terry Gammon for their efficient delivery of rare books and microfilms, and at the Russian Library at St Antonys College, Richard Ramage has cheerfully ferreted out missing data for me. My literary agent, David Godwin, has been an inexhaustible source of encouragement throughout the project; Macmillan editor Georgina Morley actively enhanced the final draft.

The Hoover Institution under directors John Raisian and Tom Gilligan, and its head of archives, Eric Wakin, have consistently supported the research, and I deeply appreciate the sponsorship of the Sarah Scaife Foundation. My thanks are also due to Andrew Romanoff, grandson of Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna, for permitting access to his familys papers in the Hoover Institution Archives.

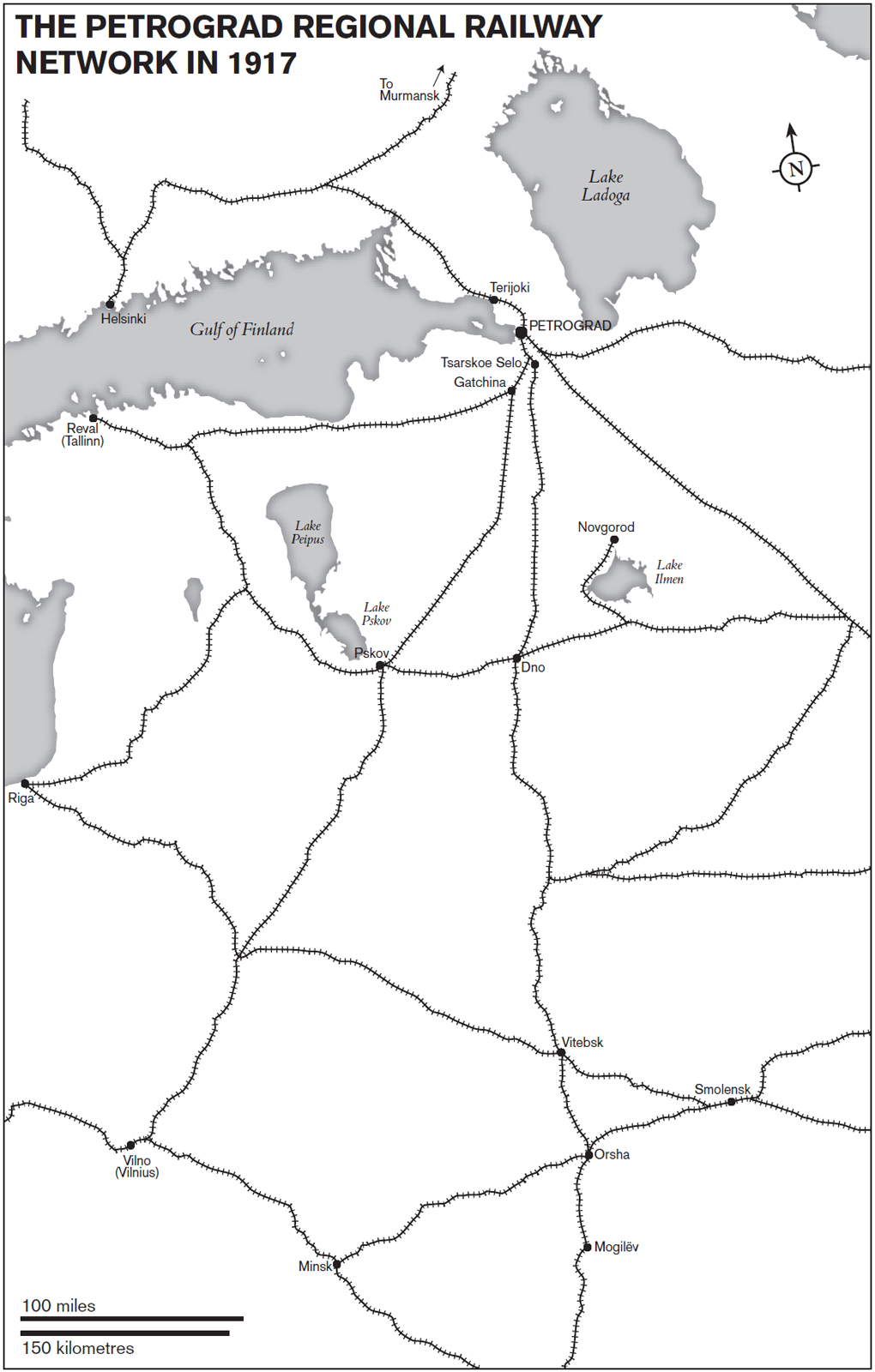

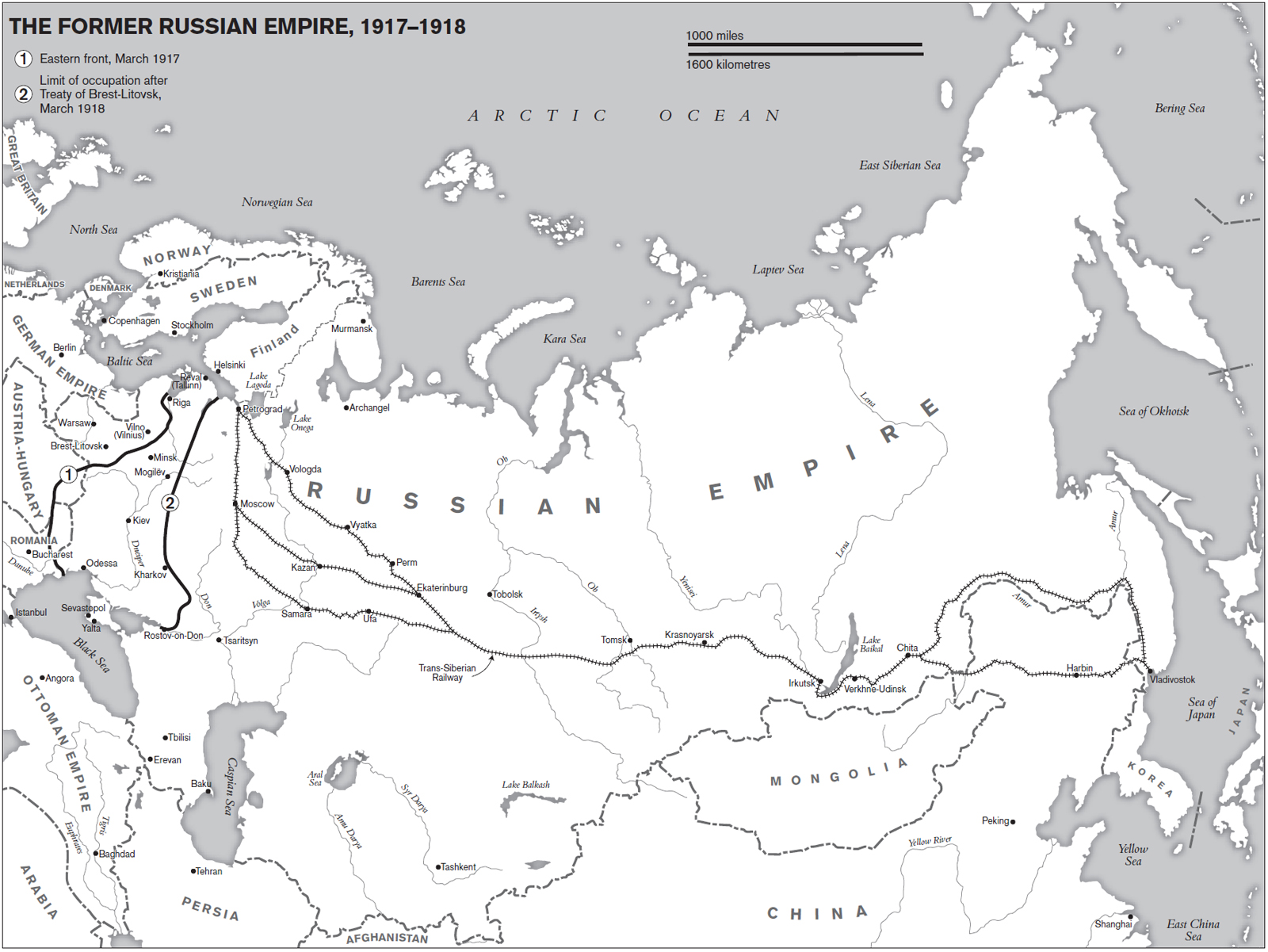

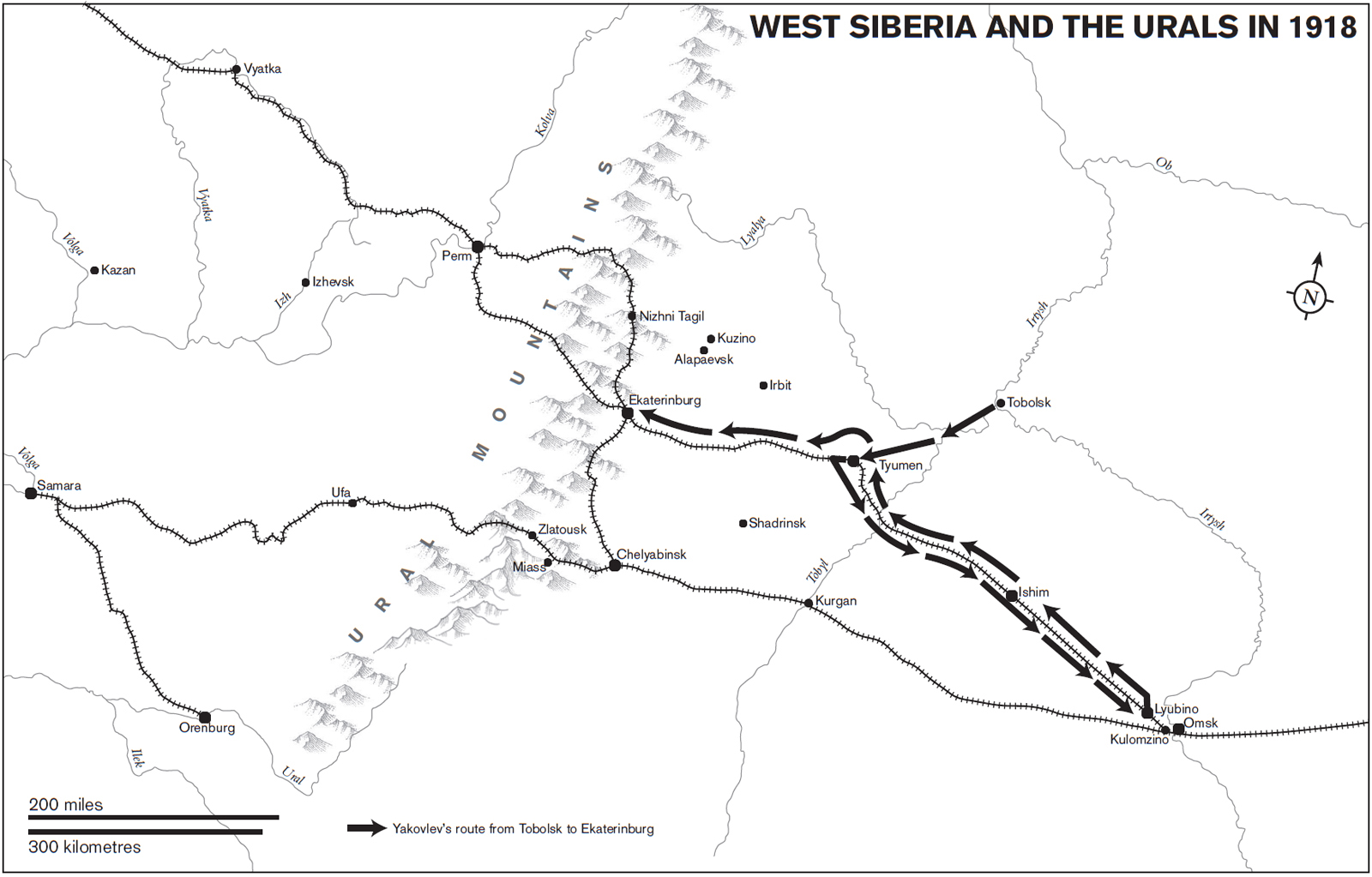

In the interests of readability I have referred to Nikolai II as Nicholas and used the conventional way of rendering names for other well-known individuals such as Kerensky (rather than Kerenski). Otherwise an amended version of the Union of Congress transliteration pattern is applied. Until January 1918, Russians used the Julian calendar, which was thirteen days behind the Gregorian one. In order to avoid misunderstanding I have changed all dates, where necessary, to the Gregorian calendar. The exceptions to this are in the endnotes where if someone continued to use the Julian system in his or her diary even after the change, I have left the reference intact and added the abbreviation OS (for Old Style) Nicholas in particular was a traditionalist who disliked any change to the way that time was recorded. All translations from the Russian are my own. I have also included maps of rail networks which, as we shall discover, are useful tools to understand events in the February 1917 Revolution as well to explain why Commissar Yakovlev took Nicholas and his family on such a strange itinerary in April 1918 before reaching Ekaterinburg.

The final draft of this book was written at a time when our family experienced an energetic burst of expansion; it is dedicated to grandchildren Lara, Dylan, Joely and Keira.

Robert Service

September 2016

INTRODUCTION

Tsar Nicholas II is a controversial figure in twentieth-century history. Admirers defend him as a loving husband and father who did his best for Russia against the tide of malignant revolutionaries who dethroned him in the February 1917 Revolution and murdered him and his family in the following year. Detractors provide a very different account; for them, he was a stubborn, reactionary tyrant whose actions destabilized the country and destroyed opportunities to avoid the catastrophe of later decades. In my opinion, it is wrong to prefer one image to the other. The truth is that he was both things at the same time, a complex, contradictory man and ruler.

I have set out in this book to look at Nicholas in the sixteen months after his fall from power. Throughout that period, he was under detention in Tsarskoe Selo, Tobolsk and finally Ekaterinburg, with little hope of release. He had seldom spoken his mind to ministers and had been notorious for saying one thing and doing another. After his enforced abdication, however, he lost the incentive to give a misleading impression except in so far as he tried to alleviate the worries of his wife and children while they were all under arrest. Parts of this story have been told many times, usually with a justified emphasis on the familys gruesome execution in a Urals cellar in July 1918 and often with less than justified claims that one or more members escaped the scene of butchery. I have come to think that parts of the English-speaking literary world have an almost sociopathic readiness to believe that a wellarmed and disciplined communist firing squad in a closed cellar was capable of such staggering incompetence. Nevertheless, the evidence, much of which has long been available, ought to be subjected to conscientious examination, and I shall endeavour to do so here.

In 1917 there was much discussion about sending Nicholas to safe exile in the United Kingdom. But even if his cousin George V had not overruled the idea, how realistic would it have been in the light of contemporary political obstacles in Russia? And what of the persisting mysteries of Nicholass troubled last journey, from Tobolsk to Ekaterinburg, in April 1918?

Although the deaths of Nicholas and his family on 17 July 1918 certainly require a fresh look in the light of old and new documentation, the previous months also call for attention. In confinement, Nicholas had the time to reflect on his period of rule since 1894. Even so, it is surprising how seldom his diary and recorded conversations have been employed to shine a light on his thinking. In addition to what he wrote for himself and said to others there is a source that has habitually been overlooked, namely the long list of literary and historical works that Nicholas read as he whiled away the period of enforced inactivity. Throughout his lifetime there was dispute about his political purposes, and his choice of books provides us with a mirror of his private meditations. Taken together, his diary, oral comments and reading material in the sixteen months before his death offer a unique chance to examine whether he had any regrets about his decisions in power. They tell us exactly what kind of ruler he had wanted to be, and they allow us to discover whether, as some have alleged, he was truly a convinced autocrat and rabid anti-Semite who made political concessions only under duress.

Next page