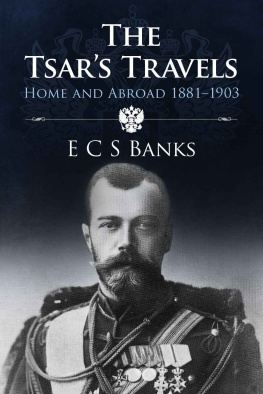

The Tsars Travels

Copyright Notice

Published in 2013 by the author

using SilverWood Books Empowered Publishing

30 Queen Charlotte Street, Bristol BS1 4HJ

www.silverwoodbooks.co.uk

Copyright ECS Banks 2013

The right of ECS Banks to be identified as the author of this work

has been asserted by ECS Banks in accordance with

the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means,

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except for

review purposes, without prior permission of the copyright holder.

All photos, postcards and images are from the authors own collection.

ISBN 978-1-78132-140-9 (paperback)

ISBN 978-1-78132-138-6 (Road to Revolution ebook)

ISBN 978-1-78132-139-3 (The Tsars Travels ebook)

Introduction

The third part of my work on the lives of the Grand Duchesses is mainly concerned with their father, Tsar Nicholas II of Russia. The girls all worshipped their father and in their eyes he could do no wrong. His daughter Olga was particularly close to him. To understand the characters of the four Grand Duchesses, it is important to understand their father. Each generation is influenced by the previous generation and that is why my books go backwards rather than forwards, profoundly influenced by Wagners Ring Cycle opera . Nicholas was himself influenced profoundly by his late grandfather, Emperor Alexander II of Russia, particularly by his actions shortly before his murder in 1881. Alexanders bravery in the face of danger was to influence Nicholas for the remainder of his life and explains why he appeared to be unmoved no matter what fate threw at him.

Nicholass early introduction to assassination was swiftly followed by an attempt on the lives of the entire Imperial family (whether by accident or design, the consequence would have been the same) during the ill fated train journey through Borki in 1888. On a tour of the Far East in 1891, Nicholas narrowly escaped death when an off duty Japanese policeman attempted to kill him with a huge sword. The tour of the Far East came at a time when Nicholas was pining for the beautiful Princess Alix of Hesse and as a result he failed to appreciate the journey as he would have done in normal circumstances.

Nicholas spent his early years in the army, where he was at his happiest. The routine of the army suited his submissive character perfectly and even when he became Tsar he preferred to adhere to a strict routine. When Nicholas finally won the hand (in matrimony) of Princess Alix, he no longer needed to make decisions. He had come to the throne shortly before his marriage and as Tsar he was able to instruct others to make the decisions on his behalf if he so wished and with Alix by his side, he was content to let her make any necessary domestic changes. In later years, when asked his opinion he would simply state that one should ask his wife, as her wishes were his. Unfortunately it meant that Nicholas could never stand up to Alix when it came to Rasputin. Despite the fact that he disliked the peasant (his sister Olga Alexandrovna claimed that Nicholas merely put up with Rasputin for his wifes sake) he did little to rid the court of the man who would ultimately be a major cause of the rapid downfall of the House of Romanov.

Nicholas as Tsarevich travelled far more widely than most royals of the era and for the first time I have attempted to provide an accurate account of his travels abroad and throughout Russia. The book naturally includes the birth and early childhood of his four daughters (his son was not born until 1904) and concludes shortly after the trip to Sarov in 1903. (The Tsar and Tsarina visited Sarov, where Saint Seraphim hailed from. Monsieur Philippe, Rasputins predecessor, who had a similar though less catastrophic effect on the Imperial couple had claimed that if the Tsarina prayed to St Seraphim she would have the son that she craved. Seraphim had not yet achieved sainthood but the Tsar obligingly rushed through his canonisation.) The story ends where the previous volume (the second) began with the wedding of Princess Alice of Battenberg, the Tsarinas niece, where the young Grand Duchesses and their cousin, Princess Elisabeth of Hesse, watched as the ceremonies progressed. The Tsars second daughter, the young Grand Duchess Tatiana, could not understand why anyone would ever want to leave their mother. She never did.

Chapter One

Spring 1881

On the evening of the first of March 1881 Nicholas noted his impressions of the day in his journal. It had not been an ordinary day. The young Nicholas recounted how his grandfathers face had been deadly pale when he had seen him earlier that day. He observed that his body had been covered in a profusion of small wounds and that his eyes were quite tightly shut. Nicholass father, then Tsarevich Alexander, had led his son to his dying grandfathers bedside. Alexander spoke to his father, raising his voice as he did so. He explained that his sunshine was there. He was of course referring to his son Nicholas. The terrified young boy saw his grandfathers eyelid flicker and his blue eyes opened and the Emperor attempted to smile.

These were the impressions that the twelve year-old Nicholas Alexandrovich made the day his grandfather, Emperor Alexander II of Russia, died. Alexander had insisted on being brought to the Winter Palace in St Petersburg in order to die with some semblance of dignity. An assassins bomb had ripped apart his body and it was a miracle he had survived even for a short time. Alexander was soon surrounded by his immediate family his son and heir Alexander Alexandrovich, soon to be Emperor, his sons wife Marie and their young son Nicholas were amongst those present at the horrific deathbed scene, straight out of the nightmares of any child.

Another of those present was Nicholass cousin and later brother-in-law (after his marriage to Nicholass sister the Grand Duchess Xenia). Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich, known as Sandro, was also a close life-long friend of the young Nicholas. Later the Grand Duke recalled the sight that greeted the family that day. He observed that the unconscious Emperor had been moved to a sofa close to the desk. Although three doctors were fussing around Alexander, it was obvious that medical science could not do anything for him. It was clearly only a matter of minutes before Alexander died. Sandro would never forget the sight that confronted him. The Emperors right leg had been ripped off in the explosion and his other leg shattered. He had a great profusion of wounds all over his head, including his face. The Emperor had one eye shut and the other was simply expressionless. The young sailor-suited Nicholas clung to Sandros arm. The Emperors daughter-in-law Marie still clutched the pair of ice-skates she had been wearing.

Someone demanded silence and announced that the end was near. The family edged nearer to the mangled corpse. The Chief Court Surgeon took Alexanders pulse and after nodding, simply let the arm dangle. The Emperor was dead. And so died the mighty Russian Emperor Alexander II, who only hours before had approved the establishment of a national representative body to advise on legislation. It was the eighth attempt on his life which brought it to an end on 1/13 March 1881. It was a date forever to be etched on the mind of the young Nicholas, who would henceforth link the two events closely: the murderous attack on his family and the legislation to reform the huge Russian empire. The date itself was one he never failed to note in his daily journal and one that would forever remain in his memory and haunt his every movement. (By a remarkable coincidence the doctor who was present when the Emperor died was Dr Serge Botkin, the father of Dr Eugene Botkin who died along with his master Tsar Nicholas II in 1918.)

Next page