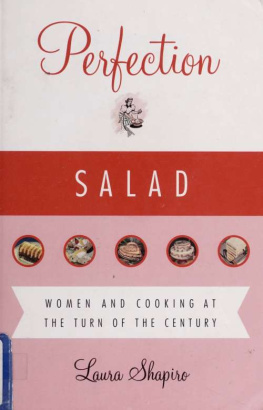

OTHER BOOKS BY LAURA SHAPI RO

Perfection Salad: Women and Cooking at the Turn of the Century

Something from the Oven: Reinventing Dinner in 1950s America

Julia Child: A Life

(Penguin Lives series)

VIKING

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

penguin.com

Copyright 2017 by Laura Shapiro

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

The author is grateful for permission to quote from letters and other materials held by the following:

The Wordsworth Trust, Dove Cottage, Grasmere; Nancy Roosevelt Ireland and the literary estate of Eleanor Roosevelt; Justice Michael A. Musmanno Collection, University Archives and Special Collections, Gumberg Library, Duquesne University, Pittsburgh, PA; the Estate of Barbara Pym; the papers of Barbara Mary Crampton Pym (191380), Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford; Julia Child Materials 2016; Julia Child Foundation for Gastronomy and the Culinary Arts

PHOTO CRED ITS :

: Artist unknown. Photo by Hugh Thomas. This image has been reproduced by kind permission of the Wordsworth family, direct descendants of William Wordsworth and owners of Rydal Mount.

: Granger, NYC. All rights reserved.

: Franklin Delano Roosevelt Library.

: Photo by Heinrich Hoffmann. Bavarian State Library Munich/Hoffmann collection.

: Photo by Mark Gerson.

: Photo by John Bottega. New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Collection, Library of Congress.

Portions of this book have appeared, in different forms, in The New Yorker and Food and Communication (Proceedings of the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery 2015) and on the website of the Barbara Pym Society.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOG ING - IN - PUBLICATION D ATA

Names: Shapiro, Laura, author.

Title: What she ate : six remarkable women and the food that tells their stories / Laura Shapiro.

Description: New York : Viking, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016057055 (print) | LCCN 2017000188 (ebook) | ISBN 9780525427643 (hardback) | ISBN 9780698178946 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: CelebritiesBiography. | Dinners and diningHistory. | BISAC: COOKING / History. | BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Women.

Classification: LCC CT105 .S465 2017 (print) | LCC CT105 (ebook) | DDC

920.72dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016057055

Version_1

For Jack

How many things by season seasoned are...

William Shakespeare,

The Merchant of Venice

Many a non-Chinese has come away from a meal cursing the inscrutable Chinese for saying nothing but bland, polite phrases, when the meal itself was the message, one perfectly clear to a Chinese.

E. N. Anderson and Marja L. Anderson, in Food in Chinese Culture, edited by K. C. Chang

CONTENTS

Introduction

T ell me what you eat, wrote the philosopher-gourmand Brillat-Savarin, and I shall tell you what you are. Its one of the most famous aphorisms in the literature of food, and I thought about it many times as I was probing the lives of the six women in this book. Food was my entry point into their worlds, so naturally I wanted to know what they ate, but I wanted to know everything else, too. Tell me what you eat, I longed to say to each woman, and then tell me whether you like to eat alone, and if you really taste the flavors of food or ignore them, or forget all about them a moment later. Tell me what hunger feels like to you, and if youve ever experienced it without knowing when youre going to eat next. Tell me where you buy food, and how you choose it, and whether you spend too much. Tell me what you ate when you were a child, and whether the memory cheers you up or not. Tell me if you cook, and who taught you, and why you dont cook more often, or less often, or better. Please, keep talking. Show me a recipe you prepared once and will never make again. Tell me about the people you cook for, and the people you eat with, and what you think about them. And what you feel about them. And if you wish somebody else were there instead. Keep talking, and pretty soon, unlike Brillat-Savarin, I wont have to tell you what you are. Youll be telling me.

One of the reasons I began writing about women and food more than thirty years ago was that I was full of questions like these, and I couldnt find enough to read to satisfy my, well, hunger. Plainly women had been feeding humanity for a very long time, but for some reason only the advertising industry seemed to care. History, biography, even the relatively new field of womens studies werent producing what should have been floods of books on female life at the stove or the table. I couldnt figure it out. Surely women spent more time in the kitchen than they did in the bedroom, yet everybody was studying women and sex, and nobody was studying women and cooking except the companies selling cake mix. Maybe because I was a journalist, not an academic, it struck me as obvious that everyday meals constitute a guide to human character and a prime player in history; but I began to see that food was a tough sell in the scholarly world. The great minds were staunchly committed to the same great topics they had been mulling for centuries, invariably politics, economics, justice, and power. Today we know that all these issues and more can be brought to bear on the making of dinnerthose stacks of books that were once missing are piled high by nowbut back then the great minds, not to mention most of their graduate students, were reluctant to descend to the frivolous realm of the kitchen. After all, academic reputations were at stake. Home cooking was associated with women, which was bad enough, and housework, which was fatal.

Luckily I had come of age writing for the alternative press, where we made a point of ignoring any precepts set down by the great minds, so when I began working on my first book there was nothing to stop me from asking people what they ate and why. I posed these questions to the dead, primarilya luxury unknown in journalism, but I realized that if I thought of myself as a writer of history, I had many more sources available and none of them could hang up on me. Over the years that followed, as I explored women and food in different eras of American life, I focused chiefly on pacesetters and enthusiasts, the women whose work in the kitchen had made an impact beyond their own lives. Then I had an experience that sent me in a different direction.

One night, bleary with insomnia, I had been staring at a bookshelf for a long time when I finally pulled out a biography of Dorothy Wordsworth. All I hoped to gain from this choice was a short, peaceful visit to the Lake District, where she famously kept house for her brother Williama visit that would lull me back to sleep. Sure enough, here was the calm, sweet record of their years in Dove Cottage: William devoting himself to poetry, Dorothy devoting herself to William, both of them aloft in reveries inspired by the mountains, the clouds, the birds, and of course the daffodils. Then William married, I skipped a few chapters, and Dorothy turned up in a dreary village far from the Lake District, now making a home for her nephew, the local curate. It was winter; she seemed to spend a lot of time trying to improve his sermons, a desultory cook was giving them black pudding for dinnerand suddenly I was wide-awake. Black pudding, that stodgy mess of blood and oatmeal, plunked down in front of Dorothy Wordsworth, the daffodil girl? There had to be a story.