This book made available by the Internet Archive.

For my parents

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2016

https://archive.org/details/perfectionsaladOOIau

Eight

An Absolutely New Product

Conclusion

A Leaf or Two of Lettuce 217

Acknowledgments

Notes

Bibliography

%

Index

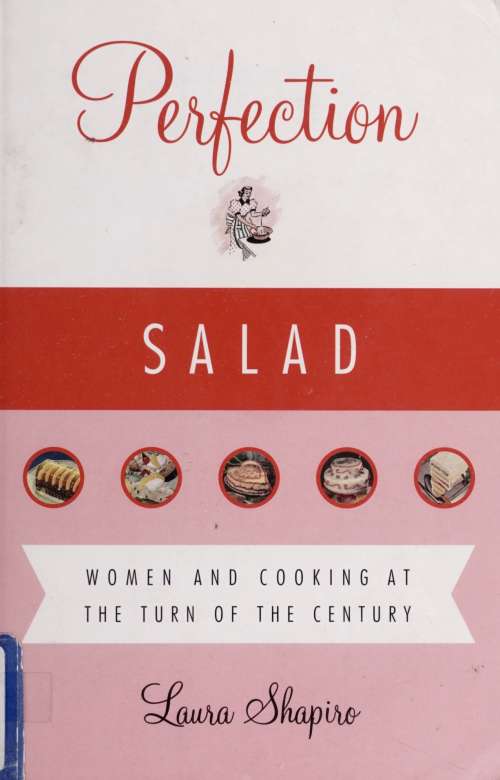

Perfection Salad

V

Prologue

Toasted Marshmallows Stuffed with Raisins

In the spring of 1923 a woman wrote to a popular food magazine called American Cookery with a question that may have been bothering her for some time:

Q: Are Vegetables ever served at a buffet luncheon?

A: Yes, indeed... provided they appear in a form which will not look messy on the plate.... Even the plebian baked bean, in dainty individual ramekins with a garnish of fried apple balls and cress, or toasted marshmallows, stuffed with raisins...

History almost never records the struggles of anxious middle-class cooks, so it is not possible to know whether this uncertain hostess really did toast a dozen or so marshmallows, pick out their sticky centers, insert a few raisins in each one, and arrange them around ramekins of baked beans; perhaps she settled for the apple balls. But the question and its answer reflect a cuhnary ideahsm that held powerful appeal for several generations of American women, beginning in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. This was the era that made American cooking

American, transforming a nation of honest appetites into an obedient market for instant mashed potatoes. The change was remarkably easy to accomphsh, although for the women who-helped to design and promote it, the pace deemed agonizingly slow and the populace distinctly stubborn. These women hved at a time when science and technology were gaining the aura of divinity: such forces could do no wrong, and their very presence lent dignity to otherwise humble hves and proceedings. Industrialization had already changed the nature of working for ones livelihood; gas and electricity were beginning to change the procedures of daily hfe; scientists and inventors were bringing forth arresting noveltiesthe typewriter, the telephone, the light bulb, the calorieon a regular basis. What chiefly excited these womenan inquisitive circle of ambitious cooks, teachers, writers, and housekeepers was the link they perceived between science and the world they knew best, the hnk between science and housework. Traditional methods of housekeeping began to look disturbingly haphazard to them, once they gained an impressionistic understanding of the principles of nutrition and the dangers of germs. Moreover, the very way women approached the days work seemed irrational and unprofessional compared with the way a well-regulated office or factory could be run. If the home were made a more businesslike place, if husbands were fed and children raised according to scientific principles, if purity and fresh air reached every corner of the housethen, at last, the nations homes would be adequate to nurture its greatness. Plainly it was their own sister, the unschooled, tradition-bound American housekeeper, who bore responsibihty for the failings of the American home, faiUngs that seemed to lead directly to poverty, disease, alcoholism, unemployment, and all the other social miseries apparent at the turn of the century. And by the same reasoning, it was the American housekeeper alone who could guide the nations homes out of their chaos and into the scientific era. During the last decades of the century, these women engendered a major domestic reform movement, which

Perfection Salad : 5

sprang up in the Northeast and spread rapidly throughout the country. It was known by several namesscientific housekeeping, home science, progressive housekeepingbut one of the most widely used terms came to be domestic science. Looking at the affairs of the household in this new hght, wrote a vice-president of one of the national domestic-science organizations, progressive women have perceived with a growing sense of freedom, how that which has seemed such endless drudgery can, by a clear understanding of underlying principles and the apphcation of scientific methods, be changed into a beautiful harmony of law and order.

This image of primitive domestic labor metamorphosing hke a butterfly constituted one of the most appeaflng messages of the domestic-science movement, and it took on special force in the room where domestic science had its earhest and most important forum: the kitchen. The women who founded and led the domestic-science movement were deeply interested in food, not because they admitted to any particularly intense appetite for it, but because it offered the easiest and most immediate access to the homes of the nation. If they could reform American eating habits, they could reform Americans; and so, with the zeal so often found in educated, middle-class women born with more brains and energy than they were supposed to possess, they set about changing what Americans ate and why they ate it. Some of the cooks in the domestic-science movement inclined toward strict functionaflsm in the kitchen and others to blatant frivohtythe cuisine they produced under the banner of science could be as dull as a bowl of dry oatmeal or as fanciful as a spring hatbut what united the cooks was their faith in the pragmatic value of each dish. Baked beans surrounded by toasted marshmallows stuffed with raisins would not have been an abomination to any of them, for the combination bespoke major utihtarian sermons. The more self-conscious domestic scientists, the ones who hked to think of themselves as laboratory technicians, would have seen the dish as pedagogical: marshmallows drawing a hesitant popu

lace to the wholly nutritious beans. The juxtaposition of a major protein source such as baked beans with an emblem of pure carbohydrate, moreover, represented to these enthusiasts a rational approach to balancing ones diet, with symbolism so stark the platter might have been a tableau vivant of nutritive strategies. Other women, especially the non-professionals who cooked only for their friends and families, would have admired the refining influence of the sweets upon the baked beans. The plebian baked bean, old-fashioned and economical, was given new status by being garnished wdth marshmallows, because sweets were very much a ladys way of assuaging her dehcate hunger. To enclose the baked beans in ramekins was to hft them yet another notch in society, for nothing was more repulsive to a refined appetite than food that looked messy on the plate. With a few raisins the dish became fit to meet the most demanding standards of health and social breeding, and might be expected to exert a pleasing moral influence as well, since a higher-class diet was known to be higher in every sense.