To my grandchildren,

Declan, Eva, and Mairead

I THINK IT IS ALL A MATTER OF LOVE: THE MORE YOU LOVE A MEMORY, THE STRONGER AND STRANGER IT IS.

VLADIMIR NABOKOV

CONTENTS

WHATEVER YOU CAN DO, OR DREAM YOU CAN, BEGIN IT. BOLDNESS HAS GENIUS, POWER AND MAGIC IN IT.

GOETHE

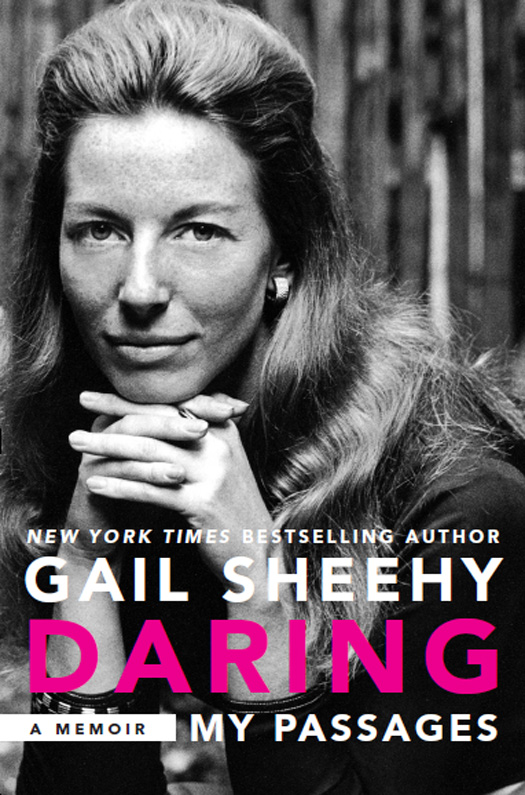

IT FELT LIKE THE LONGEST walk of my life. Sneaking down the back stairs from the flamingo-pink precinct of the Womens Department on the fourth floor of New Yorks Herald Tribune to march across the DMZ into the all-male preserve of the city room, I was on a mission. I just had to pitch a story to the man who was remaking journalism. I could get fired for this.

My boss, Eugenia Sheppard, was fiercely competitive. She would have thrown a fit if she knew I was giving my best idea to the editor of a lowly Sunday supplement. Girls in the 1960s wrote about beauty and baking and how to be the perfect engineer of that complex machinery called family life. Men wrote about serious issues. Nobody had ever thought of turning a Sunday supplement into a classy cultural magazine. But Clay Felker did. In 1965, he was incubating the future New York magazine.

Just getting a job at the famous Trib had seemed an impossible dream. Id read the paper religiously from my exile in Rochester, New York, where I was indentured in the early 60s as a PHTPutting Hubby Through. My husband, Albert Sheehy, was in medical school while I worked to support us as a reporter at the Rochester Democrat & Chronicle. Wasnt that the way it was supposed to be? He got the degree; I was the helpmeet. Thats what I thought when I married him at twenty-three, milliseconds from what was then considered a womans sell-by date. While waiting for him to finish his fourth year, Id studied the womens page of the Trib. What made it so lively? Eugenia Sheppard was the answer. She was the queen of the countrys womens-page editors, the national fashion cop and keeper of the flame of a dying social register. I wrote letters asking to work for her. Nothing. Inconveniently, the great New York newspaper strike of 196263 began in December of that year and lasted 114 days.

The strike ended shortly before my husband and I made our getaway from Rochester to plunge into grown-up life in New York City. We were imposters, of course, still just kids. Albert would disappear into St. Vincents Hospital for the next year. As a lowly intern, he was on all day and every other night, including weekends, and developed a pallor that matched his puce-green scrubs. I found a one-room garret secreted in a town house off Washington Square Park. Diane Arbus and her husband, then fashion photographers, occupied the ground floor. Never mind that we had only a pull-down Scandinavian bed, exposed toilet, and a kitchen the size of a phone booth. The garret had a big stone fireplace and lavender-and-topaz stained-glass doors that opened onto a miniature balcony. It was cheap and suited my fantasies of the artistic life.

I desperately needed a job. I paid no attention when I began upchucking in the morning (it must be the summer heat), but when I felt a faint flutter in my belly, a tickle of life, I was ecstatic. Guess what! I jumped up and down on the pull-down bed when Albert came home. Were pregnant! He danced with me on the bed. It broke. Since he was never home long enough to repair it, I slept in a V position inches off the tile floor.

Sitting before the stained-glass-window doors in the sweltering heat of August, I bent over my Singer to sew a maternity dress. I didnt know how long I could hold out before Id have to take a waitressing job. But I knew there was only one place I wanted to work, the Trib. Still no reply from Eugenia.

AN INTERVIEW WITH THE CITY EDITOR at the World Telegram and Sun started out poorly. He skimmed my clips. What makes you think a little girl like you from the boonies of Rochester can write for a big city daily?

I didnt know geography was the measure of talent.

I like the way you talk, sister! He hired me on the spot.

During my first week of working on the Telegrams womens page in August 1963, I kept hearing about an impending protest march on Washington. The country was on high alert. Images from the vicious response of Birminghams police to a peaceful protest led by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the Freedom Ridersseeing fire hoses and dogs turned on terrified high school studentsburned in memory. Medgar Evers had been assassinated only weeks before. My reportorial juices were inflamed. The march was going to be a historic confrontation. Despite dire warnings of certain violence by the government, President Kennedy was supporting Dr. King. I knew the Washington Mall would be crammed with brave black women and men. I would persuade the editor to send me. But when I told Albert my idea, he hit the roof.

Youre pregnant, are you crazy? Theyre going to teargas people. I had to admit he was right.

We watched the march on TV. When I saw, I ached to be there. I was electrified by Dr. Kings speech envisioning a day when children, regardless of their race, would be judged by their character. Seeing the mall dense with the humanity of many colors, I heard not a sound of violence, only silencerapt silence. I thought about the future of the child growing within me.

It was a hundred years after Lincolns Emancipation Proclamation, and freedom still had not been given, it had to be won. I vowed I would not spend my life watching the news on TV. I would dare to be there as history happened and write what I saw.

AT THE END OF AUGUST 1963, I was invited to interview with Eugenia Sheppard, a miniature woman perched on piano legs but a force majeure. I flattered her with my archival knowledge of her columns. She wanted me! As a feature writer! Thank God I would never again have to fake passion in print for the latest collection of Junior League tea dresses when all I wanted to do was plunge into the subcultures of New York.

I offered three weeks notice to the editor who had hired me at the World Telegram. Not surprisingly, his face screwed into a bug-eyed facsimile of a jilted lover. The World Telegram will not be used as a stepping-stone for that paper. Clear out your desk and leave.

Walking out of the papers downtown offices into the hammering heat of late summer, I was giddy with anticipation. But what would I wear to pass muster with Eugenia when I had a telltale bulge? I had been told there were two things she found abhorrentpregnancy and old age. I spent the next couple of days sewing an orange-and-purple-striped knockoff of a Marimekko tent dress that a pregnant Jacqueline Kennedy had worn in the 1960 U.S. presidential campaign.

In my first months at the Trib, I turned in the kinds of feature stories that Eugenia considered unsightly at best and radical at worstabout antiwar protesters, abortion rings, New York women doctors volunteering in Selma to sew up beaten civil rights workers, Harlem women on rent strikewhile my boss was writing about Gloria Guinness and Wendy Vanderbilt and Betsy Bloomingdale and disease-of-the-month charity balls.

Bellows wants to see you.