A LSO BY R USSELL S HORTO

Amsterdam: A History of the Worlds Most Liberal City

Descartes Bones: A Skeletal History of the Conflict Between Faith and Reason

The Island at the Center of the World: The Epic Story of Dutch Manhattan and the Forgotten Colony That Shaped America

Saints and Madmen: How Pioneering Psychiatrists Are Creating a New Science of the Soul

Gospel Truth: The New Image of Jesus Emerging from Science and History, and Why It Matters

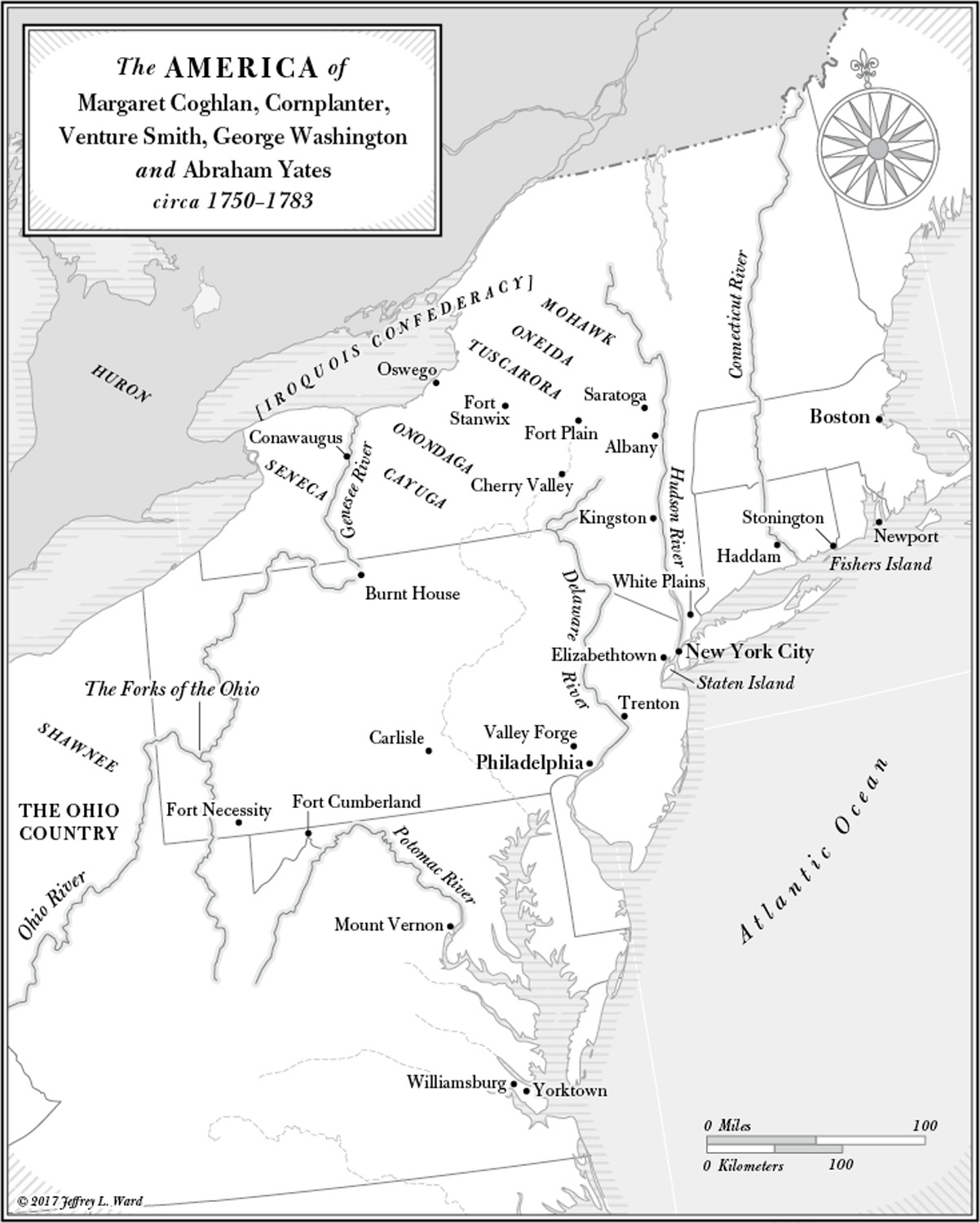

East Haddam, Connecticut, where Venture Smith chose to settle as a free man.

REVOLUTION

SONG

A Story of

AMERICAN FREEDOM

Russell Shorto

Copyright 2018 by Russell Shorto

All rights reserved

First Edition

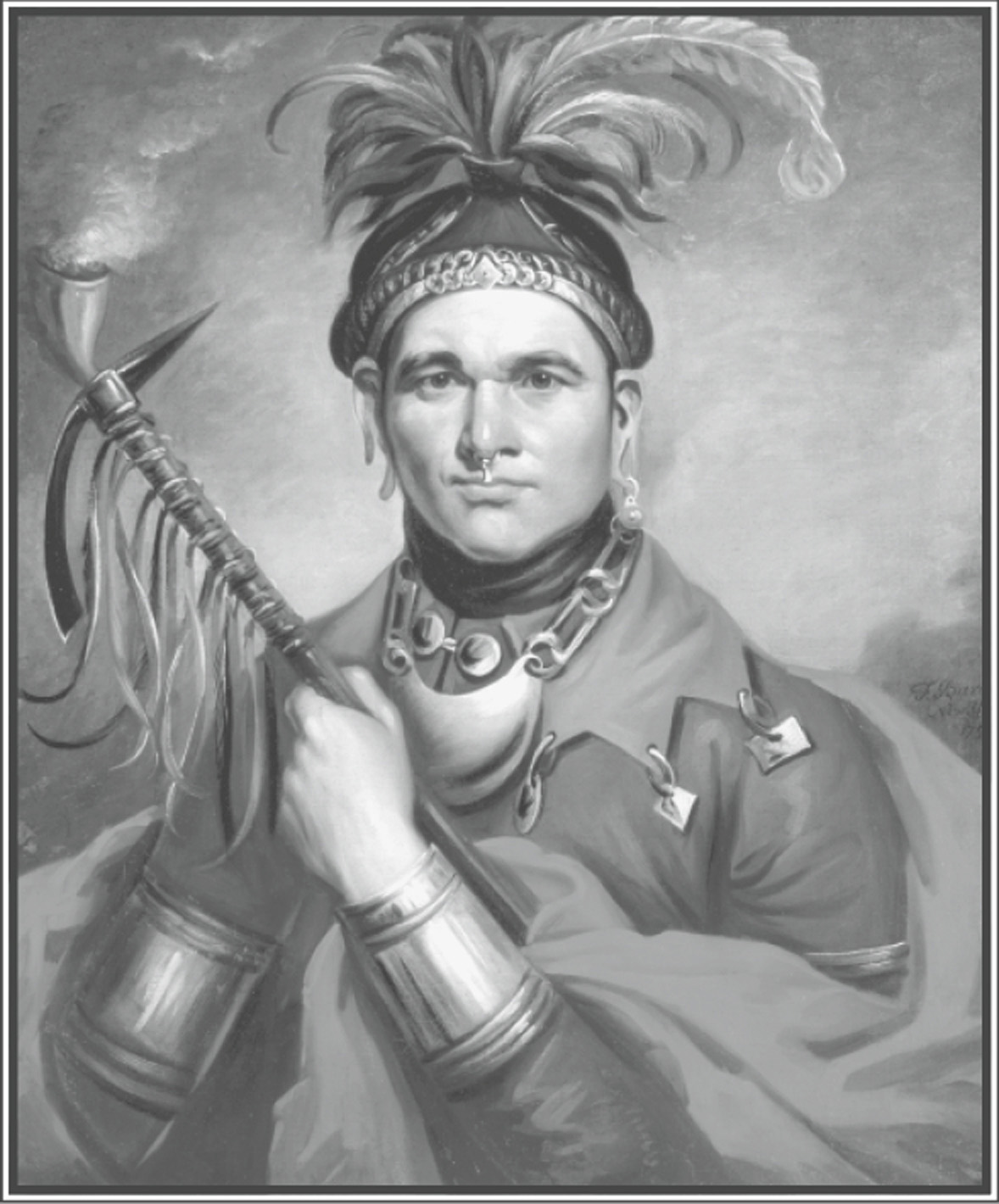

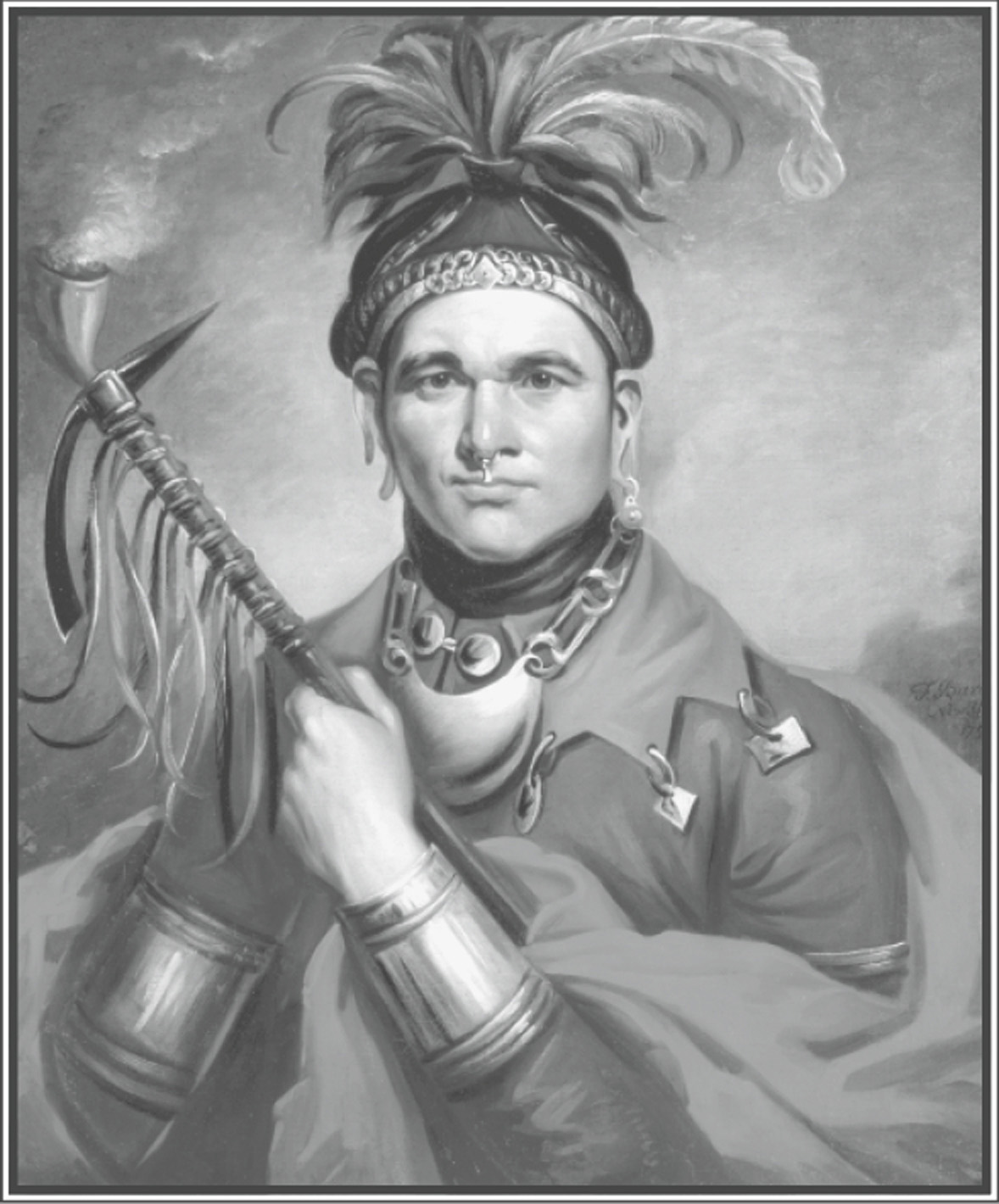

IMAGE CREDITS: Page xvi: F. Bartoli, Ki On Twog Ky (also known as Cornplanter), 1786, oil on canvas, unframed: 30 25 in.; framed: 44 in. 391 in. 5 in.; object #1867.314, New-York Historical Society. Page 12: National Portrait Gallery, London. Page 74: Washington-Custis-Lee Collection, Washington and Lee University, Lexington, Virginia. Page 394: The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, Rosenthal, Max (18331918), New York Public Library. Page 504: Letter from Margaret (Moncrieffe) Coghlan, December 28, 1803. The Robert R. Livingston Papers, New-York Historical Society. Pages iv, xvi, 12, 74, 394, 504 (background image): Abzee / iStockphoto.com.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to

Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact

W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Book design by Michelle McMillian

Production manager: Beth Steidle

Jacket design by Ploy Siripant

Jacket art: Washington Crossing the Delaware , 1851. Painting by Emanuel Leutze / Gift of John Stewart Kennedy, 1897 / The Metropolitan Museum of Art

ISBN 978-0-393-24554-7

ISBN 978-0-393-24555-4 (e-book)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

For Pamela

CONTENTS

T his is a nonfiction story. By that I mean two things: that it is true, and that it is about people, the intimate texture of their lives, the aches and sweetnesses, the things that propelled them forward in the period in which the American nation was forged.

In a sense, the American Revolution never ended. Many later events that we tend to think of on their ownthe Civil War, to give one prominent examplecan be seen as extensions of it. That is because the American Revolution was fundamentally a promise of freedom, and that promise was only partially fulfilled with the end of hostilities in 1783.

The fighting has erupted anew in our era, with such passion and intensity it is sending people back to Americas founding documents in search of answers and context. What do freedom of speech and of the press mean when disinformation can be so easily spread? What are the checks on presidential power? Have the quaint phrasings of the eighteenth century lost all relevance? If so, then who are we?

I am not offering here answers to those questions, but I am offering a change of focus. Politics is, after all, about people. The idea behind this book is that there might be insight to be gained from following the people who experienced Americas founding firsthand.

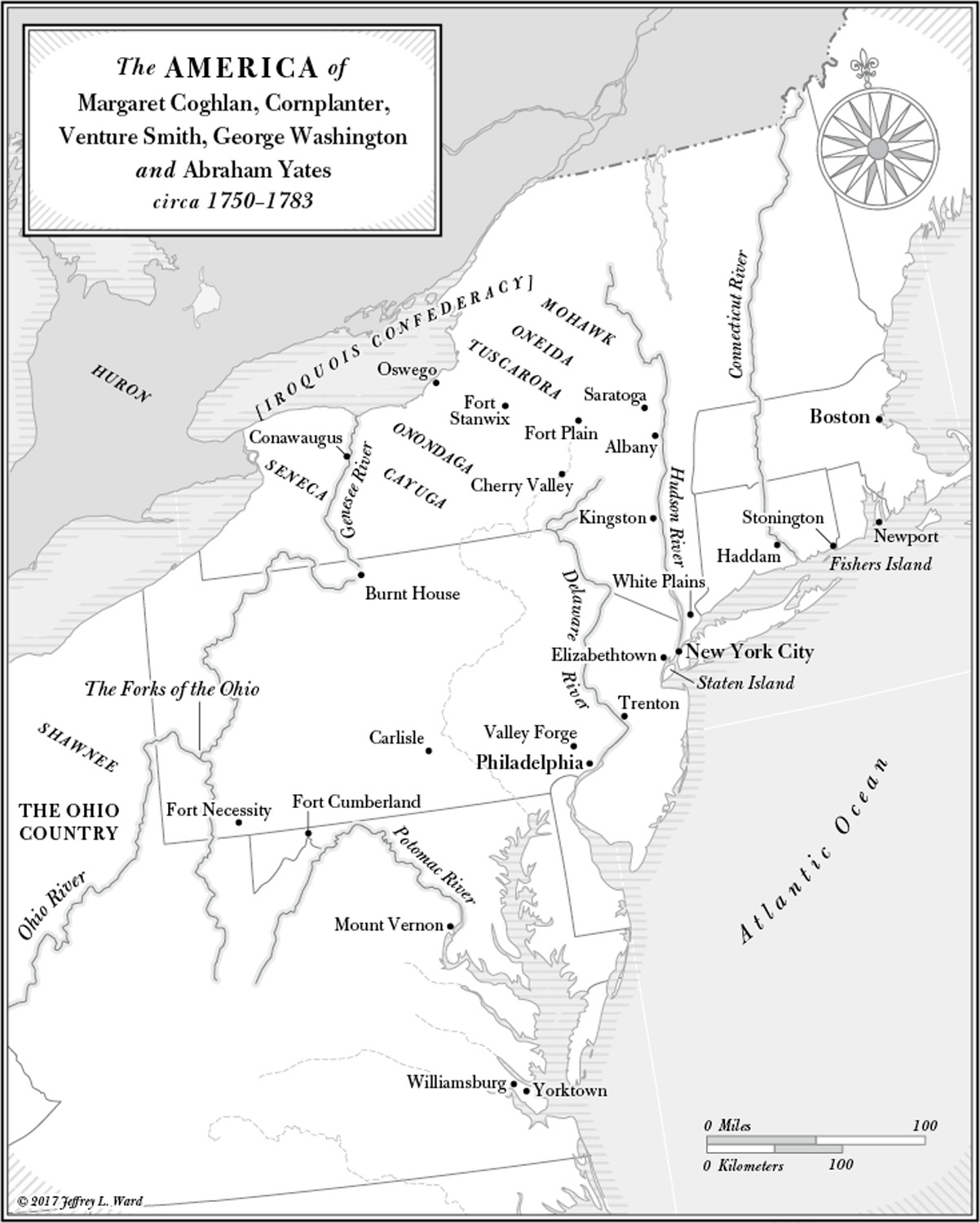

But which people? Traditional accounts of the Revolution assume that there were two sides: the British and the breakaway American colonists. That simple packaging was useful once, but it doesnt fit who we are today, and frankly it didnt fit the people of the time. There were many sides involved in the conflict, many different people writhing and clamoring and clawing over freedom. While the region of North America that broke with England was English in a sense, it was also Iroquois, Cherokee and Shawnee. It was African. It was Irish, Dutch and German. It was male and female. It was rich and poor, powerful and powerless.

This book, then, weaves six very different lives into one story. Most of its protagonists are unknown or little known today, but their very obscurity may afford a fresh way of seeing their era. I have tried not to preach or even teach in its pages. Instead, using primary source material, drawing on letters, diary entries and account books, pathetic handwritten pleas and scribbled battlefield directives, I have tried to create a kind of narrative song. The six voices sing different parts, revealing, perhaps, that we are still connected to them, that the issues that animated the people who took part in the founding of the American nation are alive in us, that we are still fighting the Revolution.

REVOLUTION

SONG

Cornplanter in 1786, painted by Frederick Bartoli.

H e was a wise man, a family man, with a kind face and soulful eyes, and he was about to kill. The people he was going to kill called themselves Americans. That word had nothing to do with him, though it would be foisted onto his identity and that of his people. He was a Seneca, a leader of the Haudenosaunee, the confederacy that the whites called the Iroquois. His name was Kaythwahkeh. Its meaning in the Seneca language had within it the idea of planting. That, coupled with the fact that corn was the most visible crop around Seneca villages, led Americans to call him Cornplanter.

Cornplanter was a young man, in the prime of life, tall, broad-shouldered, built for action. On this night, July 27, 1779, under cover of darkness, he led 120 men, armed with muskets and tomahawks, along a stream that fed into the Susquehanna River in central Pennsylvania. They surrounded a rough stockade. Inside were 21 American militiamen and about 50 women and children. At dawn one of the men in the makeshift fort appeared at the gate; the gunshot hit him with a force that knocked him back inside. Rather than accept the warning, the militiamen started shooting back. They were outnumbered and inexperienced; they had no idea what was to come. The puff and crack of musketfire filled the morning air.

Cornplanter had not wanted to be in this position: he hadnt wanted to kill Americans. But there were others who had a say, and as a political leader he understood compromise and majority rule. Earlier, at the British fort in Oswego, on the shore of Lake Ontario in Seneca country, representatives of the king of Englandalien creatures in their red-and-white dress, smelling of beef and vinegarhad organized a formal council with leaders of the Iroquois confederacy, including Cornplanter. They brought out a wampum belt whose rows of colored beads signified the age-old alliance between Great Britain and the Iroquois nation. They talked about the war that was going on between their country and the American colonists, told of the majesty and might of Britain and her king, and of the inferiority of the Americans. They wanted the Iroquois to join the fight on their side. They gave presents: brass kettles, muskets with their beautifully long and cold barrels, gunpowder, sharp knives of the kind the Iroquois preferred for scalping.

Next page