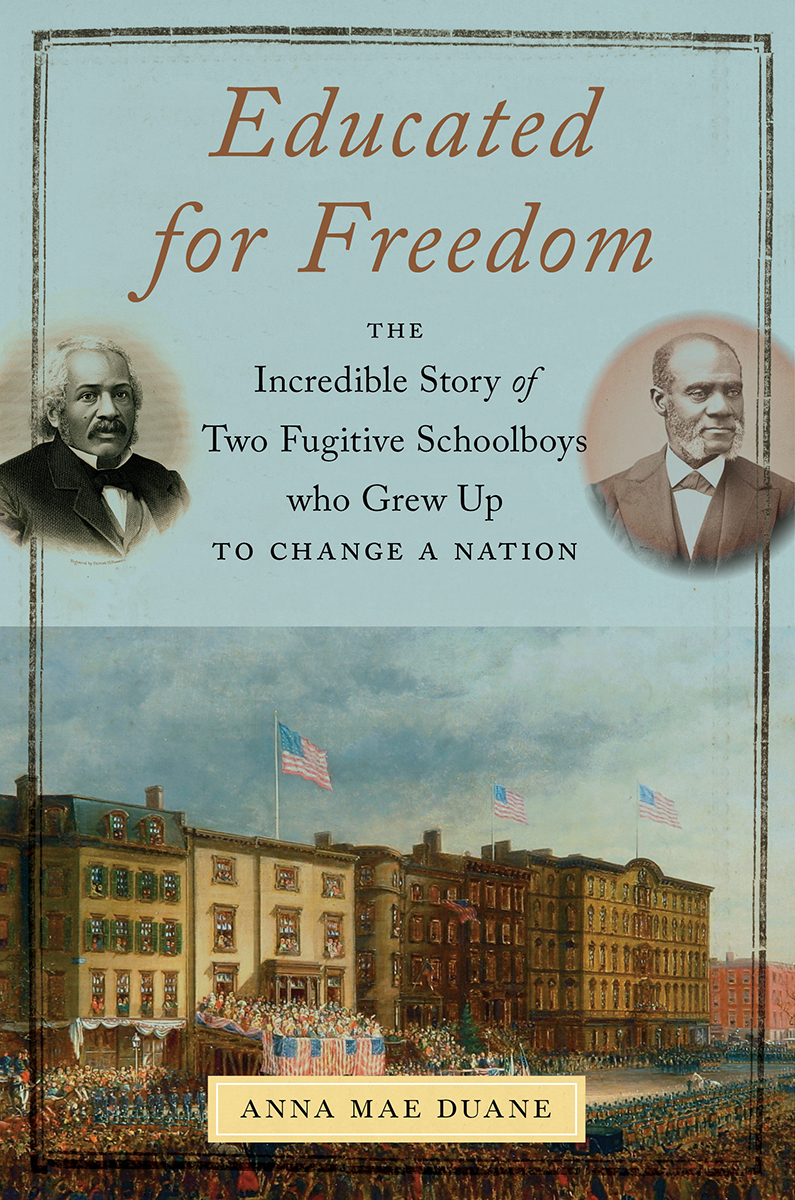

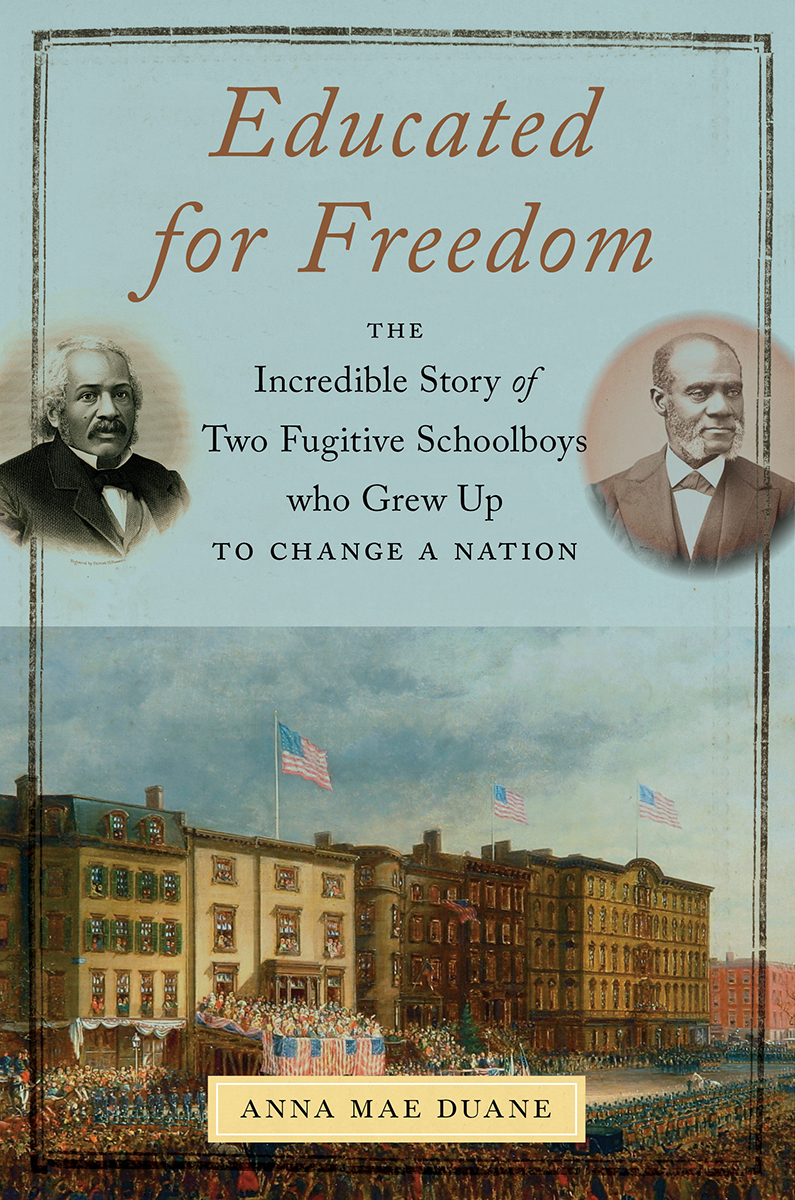

Educated for Freedom

Educated for Freedom

The Incredible Story of Two Fugitive Schoolboys Who Grew Up to Change a Nation

A NNA M AE D UANE

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

www.nyupress.org

2020 by New York University

All rights reserved

References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Duane, Anna Mae, 1968 author.

Title: Educated for freedom : the incredible story of two fugitive schoolboys who grew up to change a nation / Anna Mae Duane.

Description: New York : New York University Press, [2020] | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Summary: Educated for Freedom explores the story of two fugitive schoolboys who grew up to change a nation Provided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019006871 | ISBN 9781479847471 (cloth)

Subjects: LCSH: Garnet, Henry Highland, 18151882. | Smith, James McCune, 18131865. | African AmericansColonizationAfricaHistory19th century. | African AmericansCultural assimilationHistory19th century. | Antislavery movementsUnited StatesHistory. | New-York African Free-SchoolHistory. | American Colonization SocietyHistory. | SlaveryUnited StatesHistory19th century. | Free blacksUnited StatesHistory19th century. | African American intellectualsBiography.

Classification: LCC E449 .D835 2019 | DDC 306.3/620973dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019006871

New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. We strive to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the greatest extent possible in publishing our books.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Also available as an ebook

Contents

Rose with Thorns, artist unknown. New-York Historical Society & Museum, New-York African Free-School Records, vol. 4.

Slavery at the School Door

W HEN a fourteen-year-old Black girl took her place at the front of the Mulberry Street New York African Free School (NYAFS),the school for over twenty years. It was Charles Andrews, not Margaret, who had written the speech she was about to give.

When she finally spoke, Margaret told the story of a Black child caught between a promising future and a traumatic past. Her speech began with a hopeful look towards a future of equality, citing her own accomplishments as proof that such a future was, in fact, possible. She needed only to point you to those specimens, she told the crowd, and remind you of the exercises this day exhibited before you to demonstrate a truth. That truth, she insisted, was that Black people could, through education, grow into full, mature citizenship. Yes, the African race had long been... held in a state, the most degrading to humanity, she explained to the crowd. But they were nevertheless, endowed by the same almighty power that made us all, with intellectual capacities, not inferior to any of the greater human family.

Yet even as she looked forward to a future made possible by her own education, the hopeful world in which she stood seemed to dissolve. Margarets speech suddenly immersed herand the crowdin a very different reality. Pausing in her recitation, she looked round on my school mates and soon observed one among them who excites my most tender solicitudes. It is my Brother, she told the crowd. Looking at her sibling, she did not see the freedom that was promised to both of them. Rather, she imagined that she saw him on the auction block. Moved by the horror of the vision, she spoke of her grief in this alternate reality. Oh! she exclaimed, if I were called to part with you as some poor girls have, to part with their equally dear kindred, and each of us (like them) to be forcibly conveyed away into wretched slavery never to see each other again... In that moment, the school, the proud community members, the liberal reporters, all fell away before slaverys world-destroying power. Almost as soon as the horror raised its head in the schoolroom, Margaret banished it, telling herself and the crowd that here, in the house of learning, time moves forward, not backward. I must forbear, she told herself, looking back out at the group of well-wishers, her brother among them. Thank heaven it is not, no it is not the case with us.this look forward to her brothers future remains haunted by her vision of the slave block. Her tale of progress had been broken in the middle, the rift in her story filled with a past that cannot be left behind. Slavery in this speech works as a force of gravity, perhaps allowing a naive child to think she can jump high enough to escape, but always, always pulling the aspirant back to earth, tethering her to a landscape where youth, old age, and everything in between became indistinguishable in the fog of endless bondage.

This book is about the lessons conveyed by Margarets speech and taught for generations to Black children in a New York City school. It focuses on two schoolboys educated at Margarets school who absorbed those lessons, and who, in their struggle to transcend them, changed the nation they lived in. James McCune Smith and Henry Highland Garnet achieved unprecedented honors in a world that believed Black people were irredeemably inferior. As the sons of enslaved mothers, these schoolboy friends would meet Revolutionary War heroes, travel the world, publish in medical journals, and speak before crowds of cheering thousands. Through their work in medicine, literature, public service, political activism, and the ministry, they showed others how to reject the false choices they themselves had been taught at school: that Black people must either embrace a cheerful exile abroad or accept a living death in the United States. Their work, and that of the Black activist community they helped to lead, influenced how the United States could imagine a way to grow out of its slave past.

As two Black children who came of age and came into freedom as the country itself matured from a slave nation to federal emancipation, James McCune Smith and Henry Highland Garnet illustrate how powerfully narratives about Black childrens capacity for growth influenced the national debate about slaverys future. The school where they metand where these narratives were tested for public scrutinywas the focus of intense local, national, and even international attention. That school, part of the New York African Free School system, was first created in 1787 by a group that included Alexander Hamilton and John Jay, two founding fathers still flush with optimism about freedoms power to transform the country. That optimism had worn thin by the time Garnet and Smith graduated in the late 1820s, even as New York moved towards ending slavery throughout the state in 1827. The students literally had to fight their way through the city streets to get to class, continually harassed by poor white New Yorkers who felt excluded from the progress that these students seemed able to access.

But it was not just prejudice from outsiders that tore the school apart. The schools white teachers and trustees found themselves unable to prepare their students for a future as citizens. In truth, they simply could not imagine what that future would look like. Black parents were especially outraged by the schoolmasters belief that Black children could never grow into full maturity in the United States, and thus needed to return to Africa. Indeed, by the 1830s, almost all the schools administrators had aligned themselves with the American Colonization Society, an organization that argued that emancipation could only be achieved through exile, that somehow Americas future was doomed unless the descendants of slaves went back to the scene of the historical crime, resetting the clock on Americas original sin. The lives of both Smith and Garnet would be shaped by the powerful story that the American Colonization Society toldthat Black people were somehow lost in American time, but could grow into maturity if they returned to Africa as colonizers. Only by returning to an origin first stolen from their African ancestors, and then imposed on American-born Black people, the story ran, could Black children ever hope to grow up and assume the respect and responsibility accorded to adults.

Next page