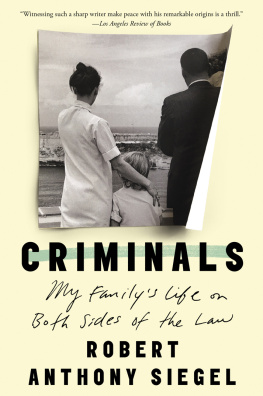

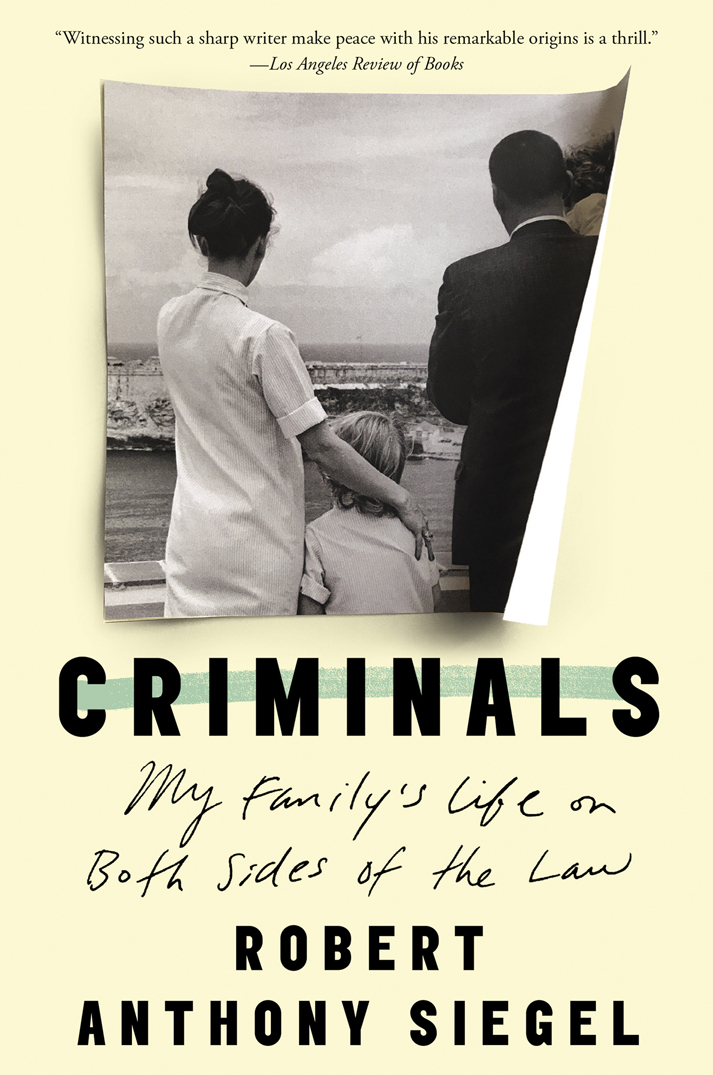

ALSO BY ROBERT ANTHONY SIEGEL

All the Money in the World

All Will Be Revealed

Criminals

Copyright 2018 by Robert Anthony Siegel

First hardcover edition: 2018

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles and reviews.

This book is a work of memoir. The events, locales, and people described are as the author remembers them.

Milk is reprinted by permission of Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins publishers.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Siegel, Robert Anthony, author.

Title: Criminals : my familys life on both sides of the law / Robert Anthony Siegel.

Description: Berkeley, CA : Counterpoint Press, [2018]

Identifiers: LCCN 2017057587 | ISBN 9781640090378 | eISBN 9781640090378

Subjects: LCSH: Siegel, Robert Anthony. | Siegel, Robert AnthonyFamily. | Authors, American20th centuryBiography.

Classification: LCC PS3569.I3822 Z46 2018 | DDC 813/.54 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017057587

Jacket designed by Donna Cheng

Book designed by Jordan Koluch

COUNTERPOINT

2560 Ninth Street, Suite 318

Berkeley, CA 94710

www.counterpointpress.com

Printed in the United States of America

Distributed by Publishers Group West

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For the chain gang

MILK

I flew into New York

and the season

changed

a giant burr

something hot was moving

through the City

that I knew

so well. On the

plane though it was

white and stormy

faceless

I saw the sun

& remembered the warning

in the kitchen

of all places

in which I was

informed my wax

would melt

no one had gone high

around me,

wheres the fear

I asked the

Sun. The birds

are out there

in their scattered

cheep. The people

in New York

like a tiny chain

gang are connected

in their

knowing

and their saving

one another. The

morning trucks

growl. Oh

save me from

knowing myself

if inside

I only melt.

Eileen Myles

CONTENTS

Memory Loop

A T THE AGE OF SIX , I struck a deal with the school bus driver: on the afternoon trip home, he would let me off at the stop where the mean kids got on. I wanted to avoid them, but that was only part of it: I wanted to be outside, in the world. I wanted to walk home.

I cant imagine why he agreed. Maybe it was one less stop to make toward the end of his run, or maybe he really believed that I could navigate the city on my own and saw no reason to cage me up in the dark and rattling bus. At very least, he must have assumed that I knew my address.

I stepped off and walked to the corner. It had never occurred to me that not knowing where I lived might be a problem. My building had a green awning and a brass door and a red carpet leading to the elevator. The windows in our living room were covered by heavy green drapes that for some reason I associated with my mother. I would wrap myself up in them, or slip past them and stand in the narrow space between the fabric and the window, looking down at the cars and the pedestrians and feeling the intense mystery of her love for me.

This is a way of saying that I could feel my homes presence among the thousands of other buildings that made up the city, could feel a path leading there as if through my own body. The light changed, and I began to walk.

Everything around me was in motion, too. People sped in all directions, plunging in and out of stores, leaping into phone booths, yelling into the black phone receivers with great passion. I couldnt believe that all this happened, invisible, while I was in school. That the world went on when I wasnt there to see.

Thats when I recognized the blue sign above Kleins department store, where my mother had bought me a suit in the husky department, a tan three-piece number with a vest and bell-bottom pants. That suit was so elegantI knew I was going right, that I would find my way home. I knew it, too, when I passed the Chock Full O Nuts, which had chromium stools lined up at the counter like giant silver mushrooms.

I passed Union Square and headed up Park Avenue, where the buildings were tall and the sidewalks always in shadow. I felt the temperature drop. I felt a lateness that had something to do with yearning. So much time had passed since the bus, since my parents in the morning. I stopped at an office building that had a small glass display case by the entrance containing maybe a dozen books with covers so ugly they were strangely beautiful. It had never occurred to me that books were made somewhere, but now I had stumbled on the place, and it felt momentous. I read the titles out loud, under my breath, as if they were the directions Id been waiting for. Then I pressed my hand against the buildings dark granite faade and felt the cold stored up there, and I knew I had to hurry.

T HREE YEARS LATER, WHEN I was nine, my parents decided to buy an apartment in a building a short walk away. The movers were coming to get the furniture and the boxes while I was at school; after school, I would walk to the new apartment instead of the old one; my parents would be there, waiting for me.

I kept putting that thought in my head and then instantly forgetting it. I had spent my entire life in the old apartment, and couldnt quite imagine us as existing completely independent of its surroundings. My mother was, to me, the woman on the couch by the heavy green drapes; my father was the man standing in the entrance to the little kitchen, taking up the whole doorway. Those spaces gave them their shapes, their lights and shadows, mixed with the touch of their hands and the sound of their laughter to make them into the people I knew as my parents.

Walking home, I kept reminding myself that I was going to the new apartment, not the old, but the idea kept falling out of my head. There were all the familiar sights to make me forget: Fourteenth Street lined with bargain clothing stores, the racks spilling out the door and onto the sidewalk; Union Square, full of light; the shadows of Park Avenue South. I became completely absorbed in the flow of the city around me, propelled onward by the hidden current, and when I turned the last corner and came to my block what I saw in front of me was not the new building but the old, its green awning with white letters, its little flower beds with their tiny white flowers. I felt pleasure and relief, all the feelings of home, and yet I knew that Id made a mistake: this wasnt my home anymore.

It was then that I realized I had no idea how to get to the new apartment. I couldnt quite visualize the route, and I didnt know the address or the phone number or even what street it was on. It hadnt occurred to me to learn those things.

I felt a surge of panic, but at the same time a wave of exhaustion so intense my eyes began closing. My love for my parents appeared as something infinitely sad and beautiful, a form of nostalgia. What I pictured were the granite ledges, the iron grates, and the empty dark basement entrances of the cityscape, all the lonely, useless places: those were me without them.

Next page