OXFORD WORLDS CLASSICS

THE LIFTED VEIL BROTHER JACOB

GEORGE ELIOT was born Mary Ann Evans on 22 November 1819 near Nuneaton, Warwickshire, on the Arbury estate of the Newdigate family, for which her father was agent. At the age of 9 she was imbued with an intense Evangelicalism that dominated her life until she was 22. Removing to Coventry with her father in 1841, she became acquainted with the family of Charles Bray, a free-thinker, and in 1844 was persuaded to translate Strausss Life of Jesus (3 vols., 1846). After her fathers death in 1849 she spent six months in Geneva, reading widely. On her return she lived in London in the house of the publisher John Chapman, editing the Westminster Review. Around 1852 she met George Henry Lewes, a versatile journalist, whose marriage was irretrievably ruined but divorce impossible. In 1854 she went to Germany with him for nine months, and for the next twenty-four years lived openly as his wife. Through his encouragement at the age of 37 she began to write fiction. Four stories, serialized in Blackwoods Magazine, and reprinted as Scenes of Clerical Life (1858) under the nom de plume George Eliot, were an instant success. Adam Bede (1859) became a best seller; The Times declared that its author takes rank at once among the masters of the art. In The Mill on the Floss (1860) and the five novels that followed, George Eliot, with increasing skill, continued the subtle probing of human motive that leads many modern critics to regard her as the greatest novelist of the nineteenth century. Lewess death in 1878 was a devastating blow that ended her career as a novelist. On 6 May 1880 she married John Walter Cross, a banker twenty years her junior, and on 22 December died at 4 Cheyne Walk, London.

HELEN SMALL is Fellow and CUF Lecturer in English Literature at Pembroke College, Oxford. She is the author of Loves Madness: Medicine, the Novel, and Female Insanity, 1800-1865 (1996) and co-editor of, and a contributor to, The Practice and Representation of Reading in England (1996). She has edited several nineteenth-century novels, including Walter Besants All Sorts and Conditions of Men and (with Stephen Wall) Charles Dickenss Little Dorrit.

OXFORD WORLDS CLASSICS

For over 100 years Oxford Worlds Classics have brought readers closer to the worlds great literature. Now with over 700 titlesfrom the 4,000-year-old myths of Mesopotamia to the twentieth centurys greatest novelsthe series makes available lesser-known as well as celebrated writing.

The pocket-sized hardbacks of the early years contained introductions by Virginia Woolf, T. S. Eliot, Graham Greene, and other literary figures which enriched the experience of reading. Today the series is recognized for its fine scholarship and reliability in texts that span world literature, drama and poetry, religion, philosophy and politics. Each edition includes perceptive commentary and essential background information to meet the changing needs of readers.

Refer to the to navigate through the material in this Oxford Worlds Classics ebook. Use the asterisks (*) throughout the text to access the hyperlinked Explanatory Notes.

OXFORD WORLDS CLASSICS

GEORGE ELIOT

The Lifted Veil Brother Jacob

Edited with an Introduction and Notes by

HELEN SMALL

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX2 6DP

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford.

It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship,

and education by publishing worldwide in

Oxford New York

Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogot Buenos Aires Calcutta

Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul

Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai

Nairobi Paris So Paulo Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw

and associated companies in Berlin Ibadan

Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press

in the UK and certain other countries

Published in the United States

by Oxford University Press Inc., New York

Editorial matter Helen Small 1999

Database right Oxford University Press (maker)

First published as an Oxford Worlds Classics paperback 1999

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographic rights organizations. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover

and you must impose the same conditions on any acquirer

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Data available

ISBN 0192832956

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Typeset by RefineCatch Limited, Bungay, Suffolk

Printed in Great Britain by

Cox & Wyman Ltd., Reading, Berkshire

CONTENTS

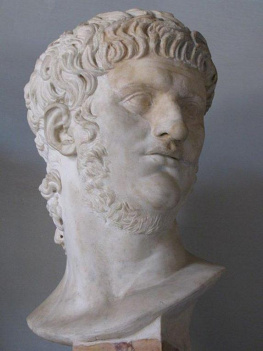

H.. Blanchon, La Transfusion du sang (1879). By kind permission

of the Bibliotque Nationale

INTRODUCTION

Much of the impact of The Lifted Veil derives from a powerful final scene which is discussed in this Introduction. Readers who do not wish to have the shock of the ending spoiled should treat the Introduction as an Afterword.

IN H.. Blanchons painting La Transfusion du sang, exhibited at the Paris Salon in May 1879, the dramatic climax of The Lifted Veil was startlingly depicted for the French public. The Salon catalogue, necessarily, provided an explanatory key:

A young and celebrated doctor, friend of M. ***, attempts a transfusion, with his own blood. The operation succeeds and the dead woman is revived. In this brief flash of life, she recognizes Mme *** who has just entered the room, and unveils her guilt: You plan to poison your husband she cries.

George Eliot, The Lifted Veil

Blanchons interpretation of the scene is superbly histrionic. In the centre of the canvas the maid (Mrs Archer) rears up in bed. Head craned forward, nightgown slipping from her shoulders, she thrusts an accusing finger at Bertha, who shrinks away to the front left of the canvas. To the right of the reanimated corpse a bewhiskered Charles Meunier in a long white surgical apron is arrested in dismay, pressing his finger to his forearm to staunch the bleeding from the opened vein. Assisting him, but almost lost in the shadows, is the inscrutable figure of Berthas husband, Latimer.

For all Eliots comparative stylistic restraint her subject-matter was undeniably lurid and it is not surprising that she worried about how The Lifted Veil would be received. At the end of March 1859 she wrote to her publisher, John Blackwood, alerting him to the storys existence and offering it for publication in

Next page