INTRODUCTION

I am a hoarder of two things: documents and trustedfriends. The former outweigh the latter in quantity but the latter outdo theformer in quality.

Details fascinate me. I love to pile up details. Theycreate an atmosphere. Names, too, have a magic, be they never so humble. Most ofthe names in this, the following account of the first thirty-nine years of mylife, are unknown to the public. For that very reason they are all the moreprecious to me.

So many strange and erroneous accounts of parts of mylife have been written since I became well known, that I felt it time to put therecord straight.

I determined to write nothing that cannot be supported bydocumentary evidence or by eyewitnesses; I have not relied on my memory alone,vivid though it is. The disturbing thing about false and erroneous statements isthat well-meaning scholars tend to repeat each other. Lies are like fleashopping from here to there, sucking the blood of the intellect. In my case, thetruth is often less flattering, less romantic, but often more interesting thanthe false story. Truth by itself is neutral and has its own dear beauty;especially in a work of non-fiction it is to be cherished. Besides, false datalead to false premises and those to false conclusions. Is it fair to scholarsand students of literature to let them be misled even on the most insignificantmatters? One writer of a recent biography, having given a false account of me ona demonstrably non-existent occasion, expressed herself puzzled at my objection.Her scenario showed me in what she conceived a good light. Be that as itmight, it was all untrue. It showed me to be a flourishing hostess at a timewhen I was little known and poor. (And one does not want ones early povertymocked.) It showed me to have among my guests two notable people who at thattime I did not know. What was damaging about the lie, the biographer wanted toknow. Damaging! Slices of three peoples biographies are falsified, mine and twoothers. But far worse than personal damage is the damage done to truth and toscholarship.

The above is only one example of irresponsible reportage;it can only confound literary history. I am sure that many of the life-storiesof my successful colleagues suffer equally.

For the memories of my early youth my best source ofconfirmation and information is my brother Philip Camberg who,being five and a half years my elder, has been able to recall names, places,dates, facts, more clearly than I could. (A childhood memory from the age offour can obviously be more clearly realized when the same knowledge andexperience were shared with a child of nine and a half.) My brother, now aretired research chemist in the United States, entered into the checking of mychildhood memories with the greatest enthusiasm.

My cousin Violet Caro also helped toconfirm my young memories, and my young cousin Martin Uezzell has been to agreat deal of trouble to look up and unearth family details. My son Robin Sparkhas looked out for me some of our family photographs to enrich the supply sentto me by my brother Philip.

When a version of my childhood experiences first appearedin the New Yorker I was delightedby the number of people who wrote to me to confirm, modify and elaborate on whatI had written. These were either eyewitness contemporaries or their children.One of my warmest correspondents is Barbara Below, daughter ofthe Professor Rule, a friend of my parents, who captured my imaginationbetween the ages of three and four, and whose wife Charlotte taught me to readand write. Mrs Below has gone to endless trouble to identify incidents anddates, and obtain for me the charming photograph of Charlotte Rule reproduced inthis book.

And what would I have done for my Edinburgh school-dayswithout the help of my friend Ian Barr and that of myschoolmates? Ian Barr, now retired, is a scholar and thinker with greatattributes of warmth and entertainment-power; he has been indefatigable inproducing data from difficult sources of information for me. Ian Barr, in thetrue Scottish style, was a young man in the Post Office before he rose to beChairman of the Post Office Board; so many years later he still remembered myparents address in Edinburgh where telegrams and special messages weredelivered. And my schoolmates; Frances Niven (now Cowell), mybest friend of those years, has helped me throughout, not merely withcorroborative facts but with the encouragement of an old and affectionatefriendship. I am grateful to Cathie Davie (now Semeonoff) whohas given me her invaluable memories of Bruntsfield Links as itwas when we walked across it in our youth. I warmly thank Elizabeth Vance whoseletters have amused and sustained me and whose vivid impressions of our life atJames Gillespies School I have quoted from. Also for anecdotal reminiscencesand amusing recollections about our school-days I thank Dorothy Forrester and Dorothy Forrest (now Rankine).

It is from the 1940s onward that I possess the greatestbulk of letters and other documents, and for her care of and deep interest inthese archives over the past twenty-four years I express my gratitude to myconstant supporter and companion, Penelope Jardine. It isthanks to her intelligent listing and docketing that I am able to lay hands onthe papers required both to stimulate and verify my thoughts of the past. It isthanks to her sense of humour that I have enjoyed what at first looked like analarming task. And it is Penelope Jardine to whom I owe gratitude for the use ofrooms in her capacious house where she has stacked, arranged and accommodatedthis accumulation of papers.

The present memoir brings me up to early 1957, when Ipublished my first novel. There are few famous names in this period of my life,but it was indeed full and rich. I hope to have given a picture of my formationas a creative writer.

I used to have an elderly friend in Rome, Lady Berkeley (Molly) whom I would sometimes visit in her flat inthe Palazzo Borghese. Molly lived in style. When I asked her about thepast, which she loved to talk about, she would send the butler for her book offamily memoirs to check the facts. I thought it an excellent idea. Perhaps weshould all write down our reminiscences to keep us from straying from reality inour latter days.

I have frequently written autobiographical pieces. What Ihave felt when composing them, and what I have experienced throughout my work onthis volume, is a sense of enriched self-knowledge. Who am I? is always aquestion for poets. I once had a play commissioned in the early days of myvocation. I met the producer for the first time one night to hand over the firstact. Next day I received a wire: Darling this is what we were hoping for. Ringme at ten a.m. tomorrow, darling. I duly phoned him at ten the next morning andgave the secretary my name. He came on the phone. I repeated my name. Who areyou, darling? he said.

I thought it a very good question, and still do. Iresolved, all those years ago, to write an autobiography which would help toexplain, to myself and others: Who am I.

I owe special acknowledgement to the New Yorker magazine in whose pages a number of the followingchapters appeared.

In addition to those of my friends and relationsmentioned above, to whom I have expressed my indebtedness, I would like to thankthe following people and institutions both for their useful volunteeredinformation and for their unfailingly cheerful responsiveness to myquestions:

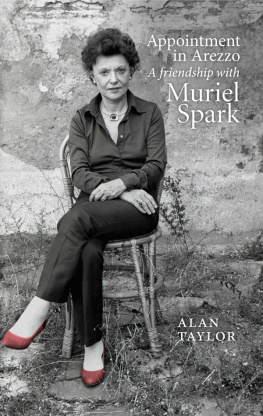

The Hon. Peter Acton; The British Council, Rome; TheBritish Institute, Florence; Mr Robert L. Bates; Mr Alan S. Bell, Rhodes HouseLibrary; Mr Nigel Billen; Mr Terence C. Charman, The Imperial War Museum,London; Mr Bill Denholm; Mr John Dunlap, Royal Mail, Edinburgh; Ms Mary Durham;Mr Tom Erhardt, Casarotto Ramsay Ltd; Mr Howard Gerwing, University of VictoriaLibrary, BC; Prof. John Glavin; Mr Chris Green, The Poetry Society, London; MsJean Guild; Ms Cathy Henderson and Ms Sally Leach of the Harry Ransom ResearchLibrary, University of Texas at Austin; Mr Hardwicke Holderness; Mr PeterHutcheon; Judge Don W. Kennedy; Prof. D.R.B. Kimbell, Faculty of Music,University of Edinburgh; The Merchant Company of Edinburgh; Mr Charles McGrathand the Checkers of the New Yorker magazine; TheMcLellan Gallery, Glasgow; Mr Michael Olver; Mr Leslie A. Perowne; Mr TerenceRanger, St Anthonys College, Oxford; Mr Kevin Ray, Washington University, StLouis, Mo.; Mr Colin Smith, Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food; Dr JaySnyder; Mr Tony Strachan; The Hon. Guy Strutt; Mr Alan Taylor, Scotland onSunday; M. Alain Vidal-Naquet; Mr Auberon Waugh; Mr Gerald Weiss; Mr AnthonyWhittome and Ms Joan Winterkorn.

Next page