Contents

Guide

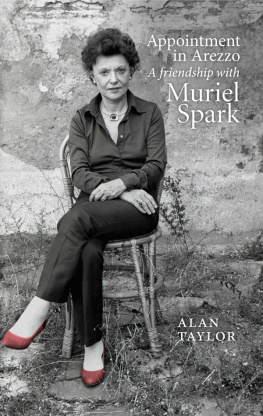

APPOINTMENT

IN AREZZO

APPOINTMENT

IN AREZZO

A Friendship with Muriel Spark

ALAN TAYLOR

First published in Great Britain in 2017 by

Polygon, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.polygonbooks.co.uk

ISBN: 978 0 5790 939 8

Copyright Alan Taylor 2017

The right of Alan Taylor to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical or photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission of the publisher.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library

Designed and typeset by Teresa Monachino

Printed and bound in Britain by T J International Ltd, Padstow

CONTENTS

Piazza Grande, Arezzo

INTRODUCTION

I may take up detective work one of these days.

It would be quite my sort of thing.

THE COMFORTERS

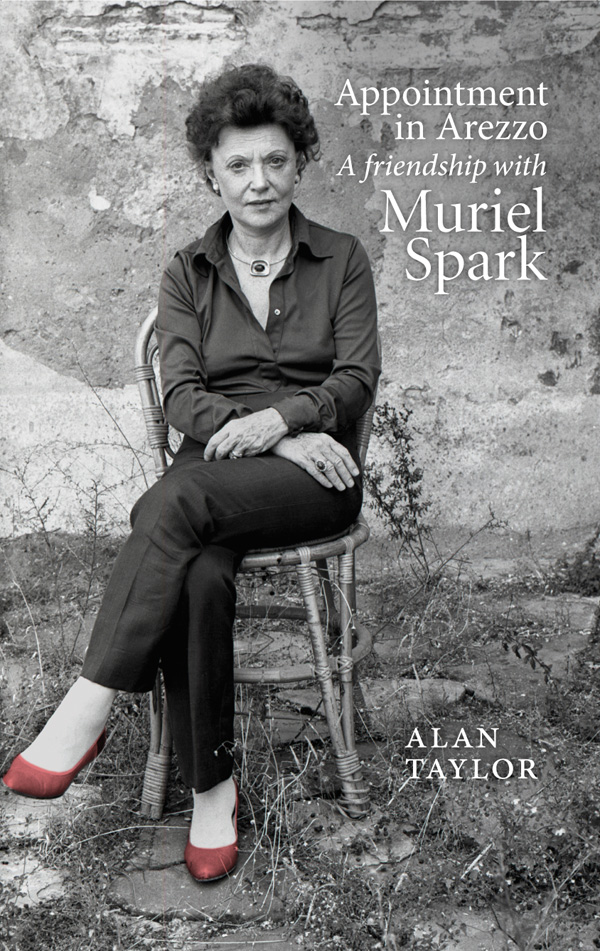

I had an appointment with Muriel Spark in Arezzo, the Tuscan town where Vasari, fabled for his Lives of the Renaissance artists, was born and bred. Mrs Sparks fax was brief and business-like. My friend Penelope Jardine and I will come to Arezzo. I suggest we have dinner there at the Continentale Hotel (not far from the station) and we can talk then. Daytimes are very hot.

The month was July, the year 1990, and only mad dogs and impatient tourists dared expose themselves to the unforgiving sun. During the mid-afternoon, when Sparks working day habitually began, I hid in the hotel and watched an Italian soap opera on television. At six oclock I took a stroll and by no grand design ended up at Vasaris house in a shaded back street in the centro storico. The house was cool, palatial, and empty save for the mute custodian who followed me from room to room with the air of someone who suspected something fishy was afoot.

In that place and at that time, the connection between Spark and Vasari seemed obvious. A fairly pious Catholic and a patriot whose allegiance was to the Medicis, Giorgio Vasari divorced himself from the religious and political issues of his day; art was his obsession. Of course, no one with even a passing acquaintance with her work would say that Spark was oblivious to great world events. On the contrary, they inform her fiction to an extraordinary if subterranean degree. From the rise of Fascism in The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie to her satire of the Watergate scandal, The Abbess of Crewe, she was always aware of what was going on in the world at large. But she was never flatly topical: no one with her intellectual attitude to faith and its implications for the hereafter could be. Like Fleur Talbot, her alter ego in Loitering with Intent, her sense of herself as an artist was absolute: That I was a woman and living in the 20th century were plain facts. That I was an artist was a conviction so strong that I never thought of doubting it then or since. Even when Fleur makes love her mind is elsewhere, despite efforts to think of General de Gaulle. How like Vasaris hero, Uccello, droning on about the beauties of perspective while his wife tries to drag him bedwards.

In the Piazza Guido Monaco, the Aretini had come out to play. Old men, gnarled as walnuts, dealt cards while their sons drank beer and their grandsons harassed pigeons. Growling motor bikes raced round the square at intemperate speed. There is carnage every night on the roads of Italy, observed Muriel as she will now be called matter-of-factly. She was a mite early for our appointment and in phrase book Italian ordered a gin and tonic while Penelope Jardine Penny parked their car. They had been together for twenty years, sharing a rambling house deep in the Val di Chiana, fifteen kilometres from Arezzo. Centuries ago the house, which is attached to a parish church, had been inhabited by a priest who added rooms as necessity determined. Two separate families had lived in it with the priest and his mother, some twenty people in all. Now it offered books a home, roughly seven thousand of them. I buy books, said Muriel penitentially, I often advertise for books; I spend a fortune. I do need rare books from time to time. We have endless encyclopaedias.

The two women seemed comfortable together, often ending each others sentences, one deferring to the other when she couldnt put a finger on a fact or recollect a date. The notion that Muriel was some kind of recluse or eccentric, as at least one ill-informed journalist had suggested, seemed absurd. Similarly, the idea of two women living together had raised prurient eyebrows. But why should it? Penny is a sculptor who has exhibited at the Royal Academy in London; she supplied the domestic and business circumstances which allowed Muriel to flourish. Penny provides Muriel with emotional security, someone who knew them both told me.

Enough emotional security to be flirting at seventy-two. I mentioned that I had tried with just a few words of Italian at my command to buy trousers in Florence. If I had told her that Id been diagnosed with a terminal illness she couldnt have shown more concern. Lets ask that dishy waiter who is the best sarto in Arezzo. While the man was summoned, Muriel asked if my hair was as nature intended. It was, I confessed. You dont do anything to it? Touch it up? I said I paid a man called Alfie in Edinburgh to keep it out of my eyes and off my collar. I never touch up mine either, she trumped.

As the waiter was interrogated about the best tailor in town I took the opportunity to study Muriel. She looked at least ten years younger than her age. Her hair, touched up or not, was red, as it was when she was a girl growing up in Edinburgh and before it was bleached under Rhodesian skies when she was in her early twenties. She was petite, with a gay and curious demeanour. She seemed to me someone to whom you could talk unguardedly, like a doctor or a priest, without fear of it ever being passed on. She dressed elegantly and expensively. Her dress was a riot of yellow and black. Round her neck she wore a string of white pearls and a canary-yellow silk scarf. She had a reputation for being waspish, once making mincemeat of a BBC interviewer who asked a fatuous question. When I told her sincerely how much I admired her latest book, Symposium, her dark eyes lit up and her face creased with pleasure.

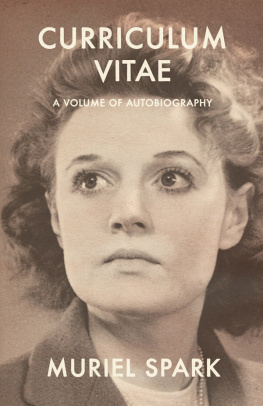

The life of a constitutional exile appeared to suit her. No one, though, should be deceived into thinking that the road to Arezzo had been straight and smooth. At that time, her autobiography, Curriculum Vitae, had yet to appear. When it did in 1992 it ended with the publication in 1957 of her first novel, The Comforters