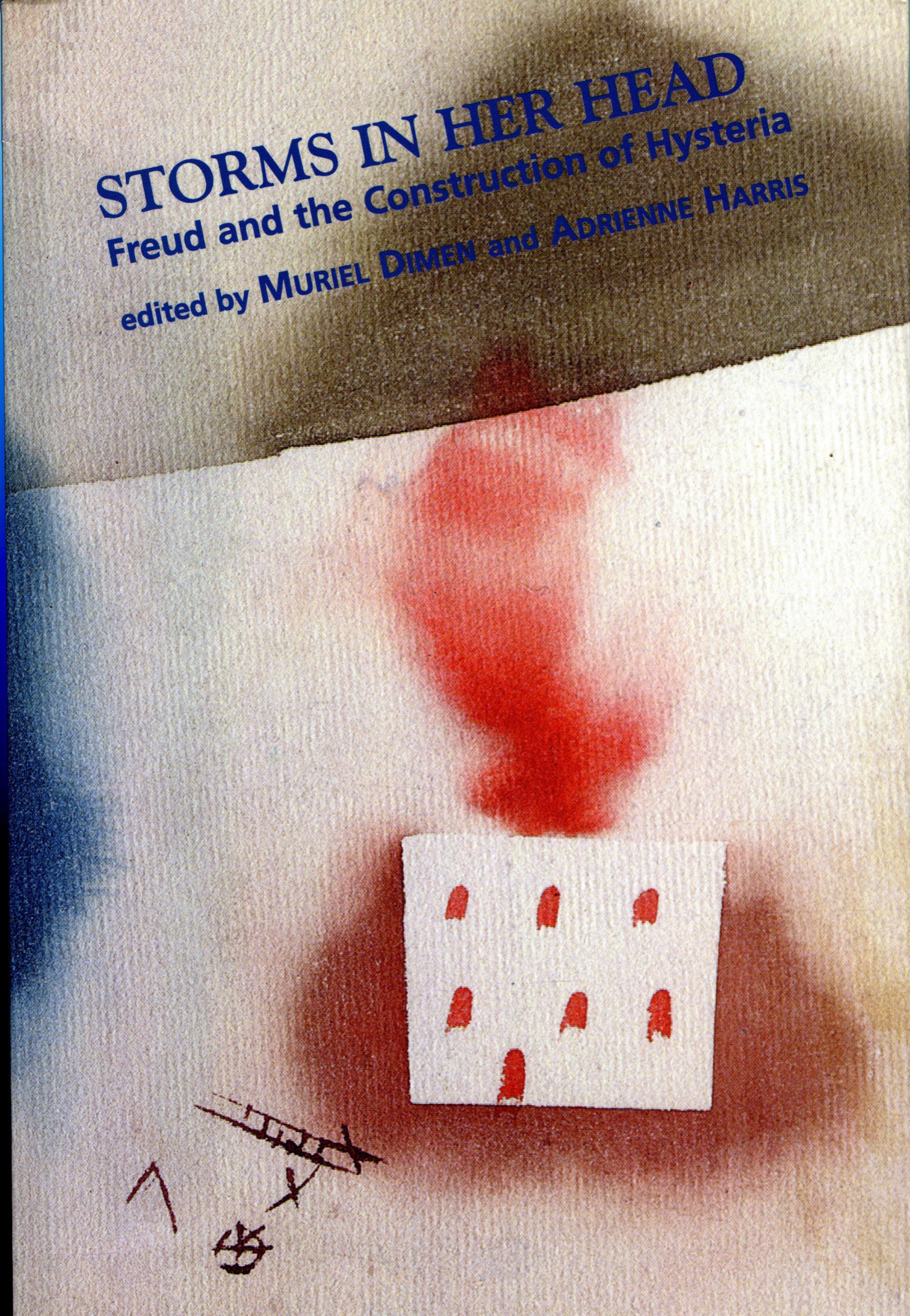

Muriel Dimen - Storms in Her Head

Here you can read online Muriel Dimen - Storms in Her Head full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2021, publisher: Other Press, genre: Romance novel. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Storms in Her Head

- Author:

- Publisher:Other Press

- Genre:

- Year:2021

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Storms in Her Head: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Storms in Her Head" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Storms in Her Head — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Storms in Her Head" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Copyright 2001 by Muriel Dimen and Adrienne Harris

Production Editor: Robert D. Hack

Ebook ISBN9781635421484

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book, or parts thereof, in any form, without written permission from Other Press, LLC except in the case of brief quotations in reviews for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast. For information write to Other Press, LLC, 267 Fifth Avenue, 6th Floor, New York, NY 10016. Or visit our Web site: www.otherpress.com.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Storms in her head: Freud and the construction of hysteria / Muriel Dimen and Adrienne Harris, eds.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1892746-23-8

1. Breuer, Josef, 18421925. Studien ber Hysterie 2. HysteriaCase studies. 3. PsychoanalysisCase studies. 4. Freud, Sigmund, 18561939. 5. Psychoanalysis and feminism. I. Dimen, Muriel. II. Harris, Adrienne.

RC532 .S58 2000

616.8917dc21

00035689

a_prh_5.6.1_c0_r0

In memory of

Donald Kaplan

and

Stephen A. Mitchell

An odd habit, reading prefaces. By convention, the reader of the preface hopes to be informed somehow of what lies ahead, perhaps even of how to read it. And yet, by turning a page or two, the reader can get to where he or she is going anyway. Why, then, does a reader start a book with a preface, simply to encounter someone pointing ahead and saying, Go to Chapter One. Im behind you all the way?

Of course, the reader will say, it is a literary convention. Books are written before they are published. And since the book wont change, except tendentiously through various acts of the readers imagination somewhere down the road, it seems reasonable to begin reading a book by hearing out another reader who has already become acquainted with it. Ordinarily this will be the author or the editors; occasionally, as in the present case, an interloper will have to do. But whoever writes the preface, perhaps we will get lucky and find out in a few quick pages something essential about the book that lies before us. It wont change, after all.

The reader who rejoins in this way is, of course, being reasonable, but only in a literate sort of way. That is to say, the reader is taking something for grantedthe existence of books and the psychic structures and mental habits formed by writing and reading booksthat need not exist at all. And by taking that something for granted, by adopting what is an essentially literate mentality, the reader is committing himself or herself to a stance on the nature of the self, on its relation to imagination, and on the therapeutics needed to keep both in good working order that may actually deceive in an important way.

Consider that in the present instance the reader holds in his or her hand a book about another book. That other book describes a heuristic rationale for understanding the formation of symptoms in hysterical patients and offers a therapeutic strategy for alleviating them. Studies on Hysteria (18931895) is over a hundred years old. It was written by two nineteenth-century Viennese physicians, one already quite distinguished at the time and the other then largely unknown, Josef Breuer and Sigmund Freud. Of course, the great likelihood is that the reader has already read that older book, which not incidentally has a preface of its own, a perfectly good one in fact, that collegially announces a slight but unavoidable degree of dissonance in the two authors views and a regrettable but equally inevitable degree of circumspection in not reporting more fully on sexual details.

How much really can that other book, more than a hundred years old, have changed? In terms of the readers imagination, one could say that it has potentially changed a great deal, especially in the last few decades. Thanks to the published researches of Andersson (1979), Ellenberger (1972, 1977), Hirschmller (1977), Fichtner (with Hirschmller 1989), and Swales (1986, 1988), the reader can compare what is written in that book with historical information, at times revelatory, that brings alive the cultural context and the nature of the caseload. The existential encounter in the case of Katharina now reads quite differently, for example. So does the case of Frau Ccilie M., which is discreetly broken up in the footnotes for reasons that become obvious when one grasps that she was arguably the richest woman in Vienna. She was not as rich, however, as another patient, Emmy von N., who could command a housecall from the junior physician in the collaboration, Freud, in faraway Zurich. The new historical information also challenges the optimistic assessment of the two doctors about their therapy. The cathartic cure of Anna O. is now known to be a fiction (see especially Borch-Jacobsen 1996); ditto the seemingly successful treatment of Elisabeth von R. Indeed, of all the cases, only that of Lucy R. remains known solely through the sympathetic account in the extant text, itinerant British governesses having the advantage over wealthy women in that they do not leave enough clues in the historical record for even the most diligent historian to track them down. But apart from Lucys story, the reader can use the existence of the new historical information to set his or her imagination free and begin changing the text as he or she reads.

The text potentially reads differently in another way, too. Where once hypnoid states and retention hysteria (either or both could be triggered by nursing a dying relative, according to the authors) had gone so far out of fashion that commentaries were required to explain their presence in the text at all, todays clinician is inclined to go back to the particulars of the case reports and see illumined therein concepts and observations that, if they cannot be called modern except through the most determined misreading, nonetheless now seem far more prescient and more suggestive of some of todays latest therapeutic theorems than they did a scant twenty years ago. The universe of clinical understanding is changing profoundly at centurys end. As the reader will see, this generates new readings of the old cases.

But in a strict sense, the cases themselves and the clinical observations of the two celebrated authors concerning them, like the book itself, have not changed. There everything still is, in the same steadfast prose, as it was more than a hundred years ago. The text is a permanent object; it connects the reader with an actual point of view and an actual past that can no longer be changed. To be sure, unless it is a first edition in the original German, the text of Studies on Hysteria is not quite on the same artifactual order as the bed that Washington slept in, or the gun that killed McKinley. But it is workably close. And for the literate mind, it is more than close. It is as exact as one needs it to be. Indeed, it is this degree of exactness, this permanence intrinsic to a book, that makes it possible for both the clinician and the historian to generate new readings, at first working alone, then by sharing their ideas, and ultimately by writing new books. It is this degree of exactness, in other words, that allows knowledge to advance in a systematic way. Similarly, it is this degree of exactness that makes revised readings, and imagination generally, safe. The literate world is a world peopled by literate selves, selves who feel themselves to be as permanent and as singular as the texts they write and read. It is alsoquite paradoxically given the sustained psychic vigor of the selves who have produced ita materialist world, a world whose permanence speaks for itself yet whose vitality has been reduced to a mindless machination of its parts through the systematic comparisons of causes and effects made possible by books. Finally, it is a historical world, a world with a past felt to be actual, not mythic. For all these reasons, it is a world where imagination is a relief, not a danger.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Storms in Her Head»

Look at similar books to Storms in Her Head. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Storms in Her Head and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.