Karaka, Corynocarpus laevigatus, leaves and berries, from

An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand, 1966, ed. A.H. McLintock.

Te Ara the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

Published by Otago University Press

Level 1, 398 Cumberland Street

Dunedin, New Zealand

www.otago.ac.nz/press

First published 2018

Copyright Diana Brown

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

ISBN 978-1-98-853130-4 (print)

978-1-98-859217-6 (EPUB)

978-1-98-859218-3 (Kindle)

978-1-98-859219-0 (ePdf)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of New Zealand. This book is copyright. Except for the purpose of fair review, no part may be stored or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including recording or storage in any information retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. No reproduction may be made, whether by photocopying or by any other means, unless a licence has been obtained from the publisher.

Editor: Erika Bky

Index: Diane Lowther

Design/layout: Fiona Moffat

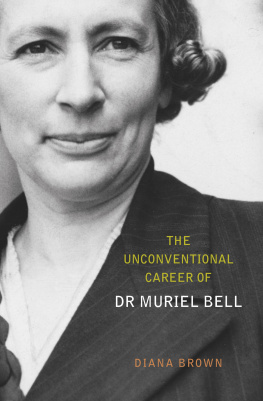

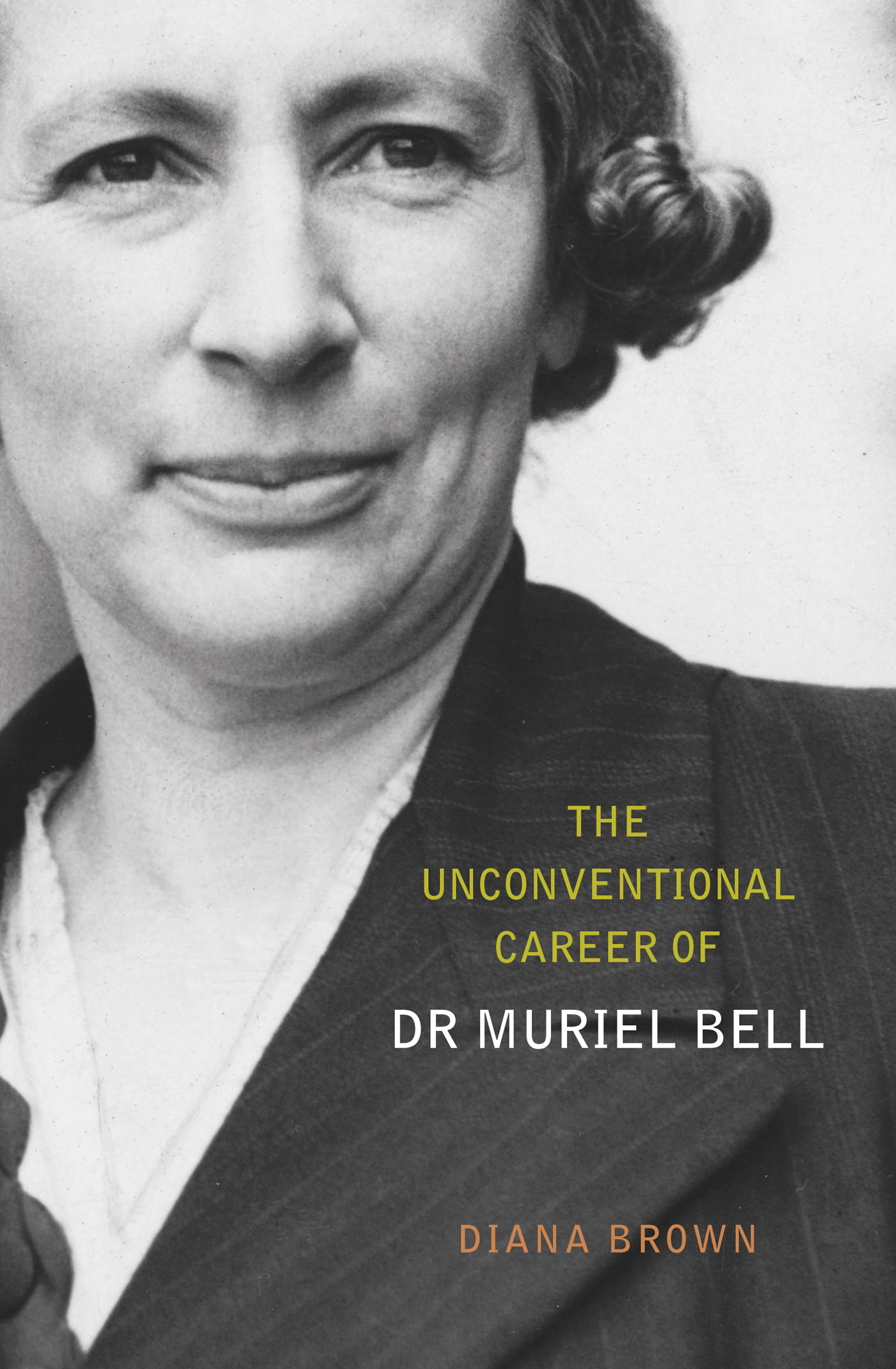

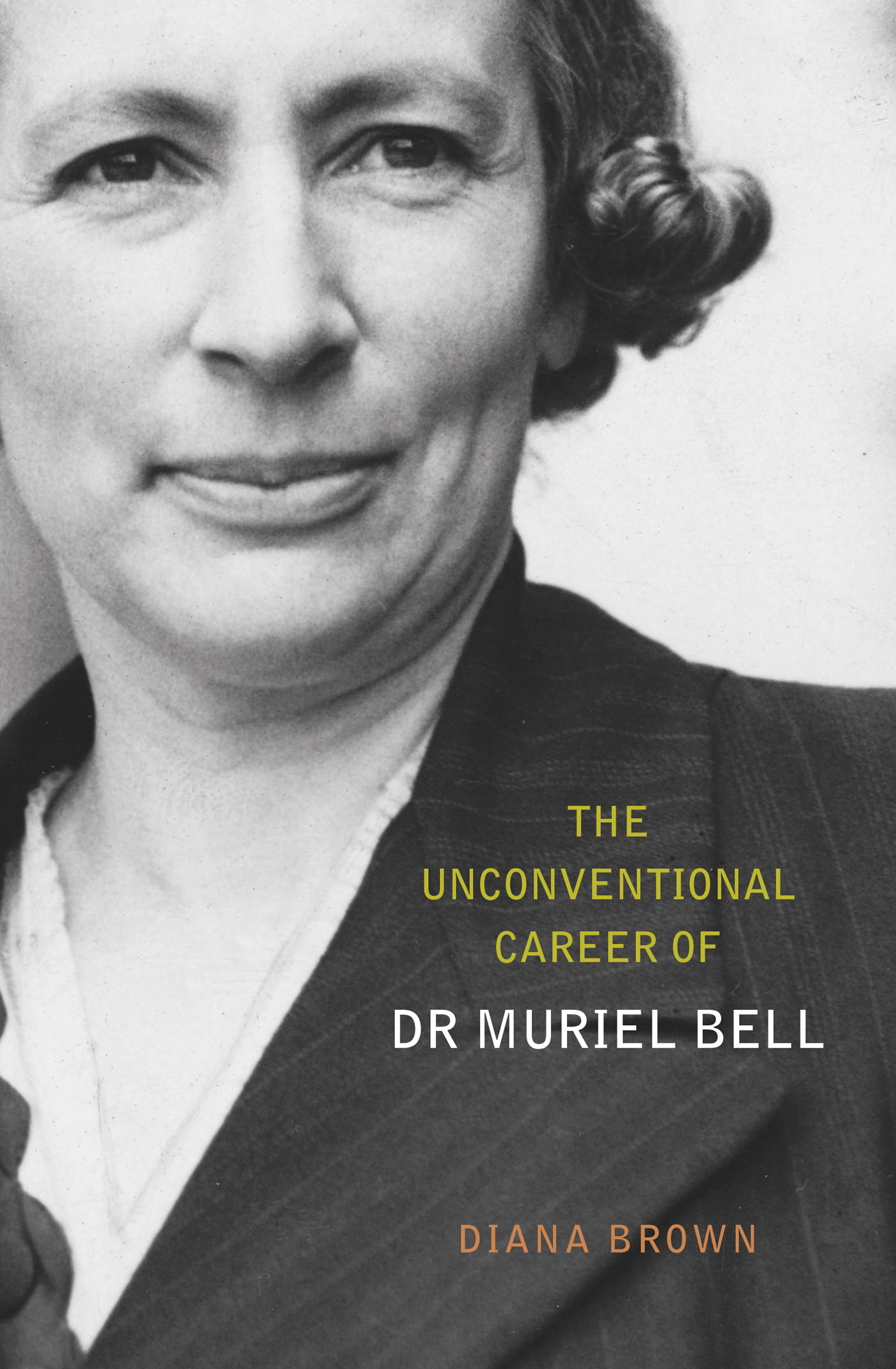

Cover: Muriel Bell, 1940. New Zealand Free Lance: Photographic prints and negatives, Ref: PAColl-6388-52, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington

Ebook conversion 2019 by meBooks

CONTENTS

D r Muriel Bell (18981974) contributed widely to the field of nutritional science throughout her career. One of the few New Zealand women of her era to obtain the research degree of medical doctor, she studied physiology and the emerging field of biochemistry, focusing on the connections between disease and nutritional deficiencies. She was appointed New Zealands first state nutritionist in 1940 and retained that position until her retirement in 1964.

Muriel Bell helped to establish nutrition and dietetics as professional fields in New Zealand. In her early research fieldwork, her capacity for what might now be called lateral thinking helped to identify deficiencies in soil minerals that were causing a mysterious illness in livestock. Experts in Britain, where she studied for several years in leading teaching hospitals and research institutions, identified Muriel as an exceptional woman with the very rare instinct of the true researcher.

As a public official, she increased scientific and popular knowledge of nutrition and radically improved the standard of nutrition in New Zealand by instituting the distribution of milk in schools; promoting the iodisation of table salt to prevent thyroid disease; campaigning vigorously in favour of public water fluoridation to combat tooth decay; and disseminating advice on healthy eating through radio talks, numerous magazine articles and nutritional handbooks like Good Nutrition. Her research on vitamins and minerals helped prevent deficiency diseases, especially in children, and her work on dietary fats and cholesterol helped to shed light on the growing problem of coronary heart disease. Her research and public service took her to Vienna, Britain, the Pacific Islands, Asia and the United States.

This work was carried out against a backdrop of dramatic historical events and scientific advances. In New Zealand and around the globe, the years spanning the two world wars exposed a wide range of health problems in the general population and gave birth to the modern understanding of public health. The Depression and years of wartime and postwar austerity had led to poverty and malnutrition. With advances in the scientific understanding of nutrition, including the roles of vitamins, minerals and other micronutrients in the body, scientists could identify specific causes for many conditions previously thought of simply as diseases of poverty, and propose remedies. Addressing such problems required cooperation and institutional relationships between the state and the scientific research establishment.

The unusual position of Muriel Bell, a woman doctor directing a government research department, owes much to her dedication and determination, and something to the common ground between nutrition and what was then known as home science. The overlap between the feminised role of women in the kitchen and the goals of nutritional science opened up the scientific field of nutrition to women. In the decades after World War II, however, as the nation prospered, health priorities changed: measures to address poverty and malnutrition seemed superfluous, and the doctrine of individual responsibility for ones well-being superseded state intervention. Nutrition no longer stood at the centre of medical and public health research, and now the strong feminisation of the field worked against it, leading to its ultimate devaluation. This trend was reflected in the disestablishment of the Nutrition Research Unit with which Muriel had identified strongly for much of her career. She felt the decision as a crushing professional and personal blow.

*

Muriel Bells life provides an illuminating view of the history of public health and health research in New Zealand, but the converse is less true. She left very little in the way of personal diaries or letters, leaving the biographer with only a collection of anecdotes and brief, vivid glimpses of experiences that beg for elaboration. Even close colleagues from later years were unable to share many insights into her personality or her life. They knew her first and foremost in her capacity as director of the Nutrition Research Unit, and this professional relationship defined the terms of their friendship.

It is hard to write a life mainly from the public record, supplemented with some oral testimony from family members, friends, former colleagues and students. Even the tenor of Muriel Bells early life in a pioneering community is difficult to gauge from local and family histories. We can discover little, for example, about how the early deaths of two siblings and her mother might have affected her. She married twice, both times to men many years older than she was; beyond the knowledge that they, most unusually for the time, took on the primary housekeeping duties, we know little about those relationships. Her own death is equally enigmatic: if she indeed took her own life, as a family member has suggested, she left only the most cryptic of clues.

It is fortunate that Muriels social connections from the early part of her adult life include such political figures as Peter Fraser and Walter Nash, which suggest a direct connection to national leaders and decisionmakers. Her friendship with the pacifist Millicent Baxter and other educated women places her in the company of committed leaders in their respective fields.

Muriel Bell distinguished herself early in her career with her unconventional (and practical) ways of doing things, whether by hurrying to patients houses by bicycle during her medical studies in Dunedin or improvising methods of chemical analysis while working at a remote sheep station. Anecdotes from those who knew her show that she was also unconventional in her behaviour and mannerisms. One of her students at Otago Medical School commented that she gave the impression of a very active bird. Her characteristic style of dress, a smock paired with open-toed sandals, revealed a woman with no conventional concern for her appearance. Ultimately, Muriel just did things her way.

Next page