To my daughters Rosie and Allegra,

their generation and those to come

Contents

Guide

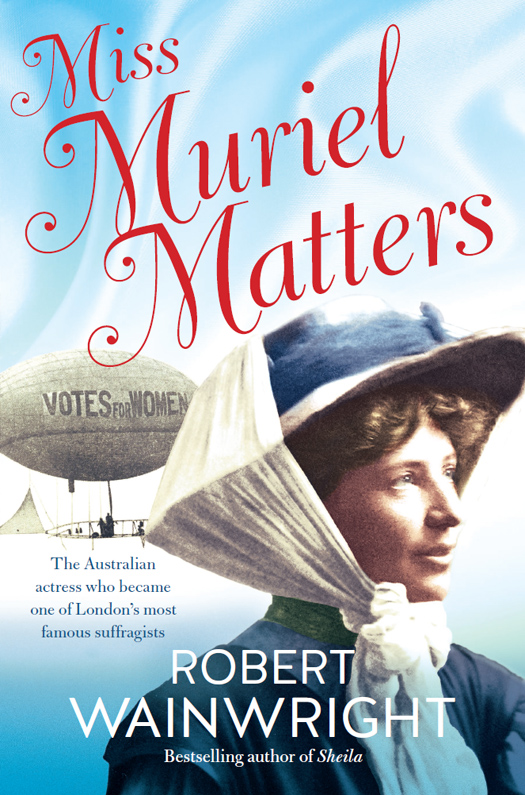

T he woman in the thick green coat and jaunty driving cap stamped her feet and danced in circles. To the huddle of reporters and photographers watching nearby, it looked like some sort of crude flamenco, but Muriel Matters was simply cold, and probably a little nervous, and a little jig might just keep her warm.

It was just after 1.00 pm on February 16, 1909 and the temperature hovered around freezing by the banks of the Welsh Harp Reservoir near Hendon in north London. Despite the cold, the journalists and a clutch of onlookers had gathered to watch an historic moment in political campaigning and the fledgling world of aviation.

Although the area had been used on and off for fifty years by aeronautical companies for experimental flights, scientific journeys and even tethered balloon rides for picnickers, this would be the first time that a powered aircraft had taken off from the green expanse that would become integral to the citys wartime defences.

And a young woman whose feet had never left the ground was preparing to take to the skies. The plan to drop hundreds of Votes for Women leaflets on the head of King Edward VII as he sat in his golden carriage trotting down The Mall to open the new session of parliament seemed crazy. But what a story!

Like many historic firsts, opinion would be divided about its sanity. Was this lady naive, reckless and foolhardy or a brave crusader? In truth, Muriel Matters fell somewhere in between; the thrill of the ride and the sense that what she was doing was necessary and would make a difference to others was more powerful than the fear of physical harm.

It would be 5 degrees cooler once they were aloft, hence the layers of heavy clothes beneath Muriels coat. Other than the cold, though, the weather was favourable: bright, clear skies with a forecast of light to moderate winds out of the north hence the need to take off from this side of the Thames. It would have been impossible to take off south of the river and try to fly into the prevailing wind toward the city. Even Hendon wasnt perfect, lying slightly north-west of the city centre, but there were few possible launch sites, highlighting the nascent and precarious nature of aviation.

Muriel looked over toward the airship, stretched out like a cigar with what appeared to be the foresail of a yacht at the rear to act as a rudder. The balloon was adorned with the slogan Votes for Women in huge lettering, so it could be seen from the ground, and streamers in the Womens Freedom League colours of white, gold and green would trail behind.

The framework beneath the balloon was a different matter, a skeletal scaffold of wires, ashwood and bamboo with a wicker gondola slung in the middle barely big enough for two people to squeeze into. Comfort was not an option in a design for as little weight as possible.

She focused on the man scurrying around the airship. Henry Spencer, the pilot, looked a bundle of nerves checking the struts and ties and engine, which seemed tiny for its job of driving the airship in a series of yacht-like manoeuvres across the prevailing winds to position it over the Houses of Parliament as the Kings procession made its approach.

As she watched and waited, Muriel might have reflected on her incredible life transformation. It seemed only yesterday that she was in the city of Adelaide on the other side of the world, enjoying the plaudits of critics as an aspiring actress, an elocutionist who could hold the attention of audiences for hours as she recited great dramatic verses. She had travelled across the world in pursuit of those dreams, had been welcomed in some of Londons great entertainment venues but then decided she had a greater calling than footlight fame, a calling for which she was prepared to risk her life.

It was almost 1.30 pm, lift-off time if they were going to get south to Westminster and greet the Kings carriage. Several men moved forward, loaded the bundle of pamphlets and then lifted Muriel into the basket while a dozen more clung onto ropes attached to the framework to steady the ship.

But there was a problem. The motor wouldnt start. All Muriel could do was busy herself, stacking the pile of pamphlets neatly and fastening her hat to her head with a scarf tied beneath her chin. She smiled and posed for the cameras, a megaphone clasped casually in gloved hands. In the background Henry Spencer looked on anxiously.

Finally, after furious minutes of tinkering, the engine spluttered into life and the giant ship lifted slowly into the air. Muriel Matters had taken flight.

Mary Matters, a widow with four children and an ageing mother, wrote asking permission to depasture her cow on the parklands free of charge. Communications favourable to the request were received from Mrs Gawler and Dr Whittell. Referred to finance committee.

South Australian Register, August 10, 1862

T he request made of the Adelaide Municipal Council seemed reasonable enough. Even a neighbour, a Mrs Gawler, and a respected GP, Horatio Whittell, a man of high character, integrity and ability, according to the same newspaper, felt compelled to support Mrs Matters case for recognition of hardship, but the men of the council took a different view.

As trifling an issue as it appeared to be for a council in charge of a growing city, the widows request was shunted off to a committee where it would be denied out of hand, the august body of gentlemen deaf to the plea of an enterprising woman with no husband that she be allowed to feed her only asset a cow on public land, even though it would help keep the grass down.

It was a mean-spirited decision by the male political elders of a colonial city supposedly rooted in a spirit of entrepreneurial endeavour and equity. The travails and challenges of a widow seemed to have no bearing on their considerations. If anything, it annoyed them that a woman would seek to challenge laws enacted by men.

Adelaide, capital of the freely settled colony of South Australia, had been founded less than three decades before, designed by the Surveyor-General Colonel William Light in a grid pattern on either side of the Torrens River: broad avenues, narrower streets and public squares surrounded by great parklands filled with trees that would help keep the air clean, in contrast to the poor light and dank, polluted air that permeated most overcrowded European cities.

The genius of Lights design was matched by the utopian impulses fuelling both his garden citys construction and the settlement of the colony. Adelaide was not to be built on the back of convict labour, like the east coast capitals of Sydney and Melbourne, but as a free settlement, financed by selling investment parcels of land to the wealthy in faraway Britain. The proceeds from the sales (to largely absentee landlords) would fund the cost of shipping a ready-made working-class population from the United Kingdom to build the new city.

The great experiment in the art of colonisation was considered an immediate success. The initial land release sold quickly and a campaign was launched in London to lure settlers across the seas with promises of a paradise: a new society that championed civil liberties, tolerance and religious freedom, far from the human crush and crime-filled streets of the Mother Country. So bright was this beacon that no jail had been planned, let alone built, for the city named by William IV after his German wife.

Free passage was offered to men aged under forty-five, single or married, who were skilled farm labourers, shepherds or copper miners, interested in living and working in the rich agricultural regions opening up outside the city. There was also room for men good with their hands who could help build the city that was fast rising from the riverbanks bricklayers, stonemasons, farriers, gardeners, sawyers, carpenters, mechanics, wheelwrights and the like, provided they were sober, industrious, of general good moral character... free of all bodily and mental defects.