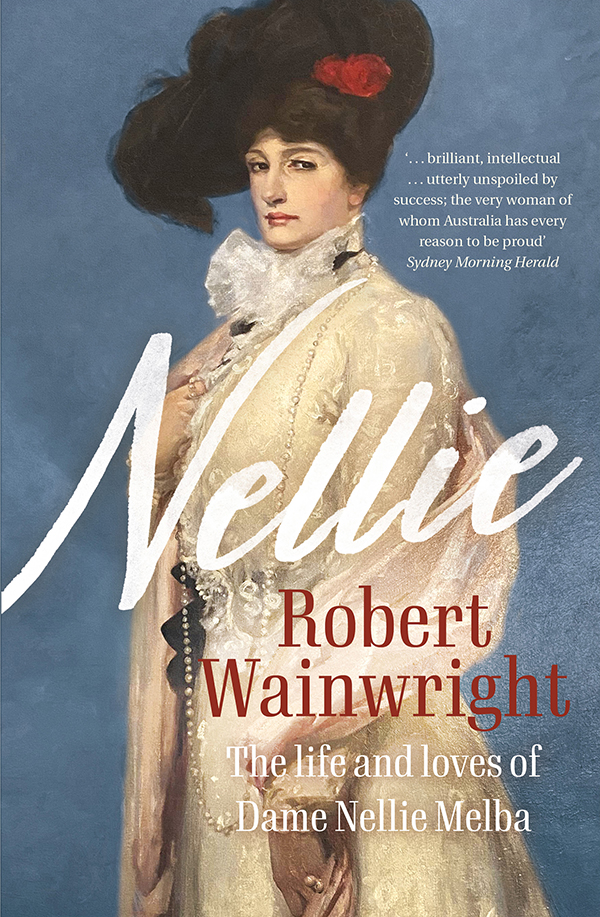

Helen Porter Mitchell was an unusually naughty child; incorrigible, unreasonable and unmanageable, incapable of behaving even by accident. These were her own words, an unkind self-assessment delivered much later in life, possibly as a means of justifying why her parents did their utmost to prevent her from pursuing a career as a singer.

Her father, David Mitchell, was a God-fearing man who would have regarded his oldest daughters voice as a heavenly gift, and yet he could not abide the notion of her taking the stage professionally. It was one thing to sing at a charity concert for the church or the local school but entirely another for a woman to warble for moneyshilling entertainmentsmuch less in costume and grease paint. That would be promiscuous and lacked respectability before God; and his Nellie, as Helen would always be known, would not be a part of it.

When she was an eager teenager, Nellie decided to hold a drawing-room concert to raise funds for the repair of a cemetery fence at the local church. She wrote to friends asking them to donate and attend the concert, even creating and pasting colourful posters on walls around the neighbourhood advertising the show, but when her father heard about the event he wrote to each of the invited guests asking, as a personal favour, that they stay away. When Nellie stepped out onto the makeshift platform there was an audience of just two. She sang anyway but never forgot the experience.

Neither time nor her success would dull her fathers hardline view. Many years later, when she returned to Australia as the most famous soprano in the world, Nellie sang in Scots Church, Melbourne, which her father had built. It was a magnificent homecoming and yet, afterwards, when she asked her father if he had liked her singing, his only response, delivered in his gruff Scottish burr, was I dinna like your hat.

And yet her father was her hero; a strong and dependable rock but impenetrable and unyielding.

David Mitchell had arrived in Melbourne penniless and yet he made a fortune, hewn from his learned skills as a stone mason. He was responsible for many of Melbournes most enduring structures, including the Royal Exhibition Building.

He met dark-eyed Isabella Dow, the daughter of a business associate, at church one Sunday in 1857 and they married a few months later. They would start a family immediately but, tragically, their firstborn, a girl, and then a boy would both die in infancy. Nellie was their third child, born on 19 May 1861. The Mitchells watched anxiously over her and celebrated with prayers when she reached her first birthday.

There would be another seven Mitchell children, roaming around a large, turreted house called Doonside, built by their father in inner-city Richmond, but Nellies heart lay at the end of an 80-kilometre stagecoach ride out of the city to an old cattle station known as Steels Flats, which was beyond the town of Lilydale.

It was here that she thrived, happy fishing or swimming alone in the nearby creek, exploring bush tracks and gullies beneath towering eucalypts filled with raucous birds or clambering into the foothills of the ranges behind the homestead; her wanderings limited only by the endurance of her pony and her imagination.

Nellie was a contradiction, a young woman who was happy in her own company and yet someone who needed affirmation. She was stung by criticism but ultimately used it as a driving force to succeed.

But it was her father she so desperately sought to please. If he was a stern master then I was a willing pupil, she would later write in her memoir. As much as she looked like her mother, it was her father after whom Nellie took; they were both resourceful, fearless and determined but also stubborn and quick to angercharacter traits that would serve her well but also have consequences.

She could never say from where her abilities came. David and Isabella Mitchell were both musical but neither was more than accomplished, and certainly far from extraordinary. Nellie would sit beside her mothers feet as she practised the piano and on her fathers knee as he played the harmonium.

Singing seemed as natural as breathing, her constant humming around the house an irritation to her mother but, in retrospect, an unintentional vocal exercise that helped develop her famous trill.

Nellie was six years old when she performed at a Sunday school production and just eight when she sang in public for the first time, at a fundraising concert in the Richmond Town Hall in which she accompanied herself on the piano and earned several encores. An enthusiastic reporter from The Australian newspaper observed: She is a musical prodigy and will make a crowded house whenever she is announced again.

Nellies parents were hoping for docilityfor their daughter to conform to the expectations of the time that young women should stay quiet and not express an opinionbut they only succeeded in entrenching her rebellion and forming an enduring sadness about being misunderstood. She hated the strict boarding school she was sent to, especially as it was so close to home she could see her father riding to work.

Those memories would never fade: A girl should not be brought up too strictly, she remarked in an interview in 1910. Particularly, she ought to be allowed to choose what she will do with her life.

Although she found school distressing, it was the music program at the Presbyterian Ladies College, East Melbourne, that set her on the pathway to success. It was here she found her first singing teacher, Mary Ellen Christian, a concert contralto who had studied at the Royal Academy of Music in London. When she left school, Nellie continued studying singing with Pietro Cecchi, a tenor who had studied in Romes Academy of Music. The foundations had been laid.

Nellies mother died in October 1881 at the age of forty-eight. It wasnt unexpectedshe had been ill with chronic hepatitis for some timebut, even so, her death from liver failure came as a shock.

In her last days, she had made Nellie promise to take care of the youngest child, four-year-old Florence, known as Vere. Not simply to watch over her but to protect her as a mother.

In the bleak months that followed the funeral, Nellie, aged twenty, felt the weight of that solemn vow. The sight of Isabellas body being lowered into the ground in a coffin and covered with dirt was haunting. But death was also a beginning, and there were consequences for the living; her little sister had become a responsibility in a life that, until now, had none.

Nellies response was to move Veres cot into her own room, to tend the child as one would a newborn baby. It was as if she could not let Vere out of her sight lest something happened and yet, despite her attention, one evening barely three months later Vere fell ill. It was too late to call a doctor, so Nellie put the feverish girl to bed and hoped her temperature would subside by morning.

Unable to sleep, she listened with increasing concern to Veres wheeze, clearly the girl had an infection in her chest. As she finally began drifting off to sleep, Nellie was disturbed by the sense that a third person was in the room. Unable to rid the notion, she sat up to see what she thought was a dark figure near the fire. In her anxiety and drowsiness she pictured her mother wearing the simple black dress in which she had been buried. Nellie watched, transfixed, as the spectre moved slowly across the room and stood over Veres cot where it raised its hand and pointed at the child before making a sweeping motion and disappearing. Nellie raced to the cot where Vere was asleep, peaceful and cooler to the touch. Was it possible or the hallucinated vision of a stressed mind?

Next page