Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

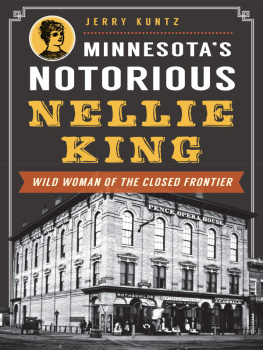

Copyright 2013 by Jerry Kuntz

All rights reserved

First published 2013

e-book edition 2013

Manufactured in the United States

ISBN 978.1.62584.676.1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kuntz, Jerry.

Minnesotas notorious Nellie King : wild woman of the closed frontier / Jerry Kuntz.

pages cm

Summary: The story of Nellie King, a woman who hoodwinked and swindled the residents of the Dakotas, Minnesota and Northern Wisconsin in the late 1800s with her fetching appearance, eccentric behavior and criminal misdeeds-- Provided by publisher.

Includes bibliographical references.

print edition ISBN 978-1-62619-207-2 (paperback)

1. King, Nellie. 2. Swindlers and swindling--Minnesota--Biography. 3. Female offenders--Minnesota--Biography. 4. Women adventurers--Minnesota--Biography. 5. Minnesota--History--19th century. 6. Minnesota--Biography. 7. West (U.S.)--History--1860-1890. 8. West (U.S.)--History--1890-1945. I. Title.

HV6692.K56K86 2013

364.163092--dc23

[B]

2013034556

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

CONTENTS

Chapter 1

NELLIE THE FEMALE DETECTIVE

The September 30, 1887 edition of the Aberdeen (Dakota Territory) Weekly News featured the following article on its first page:

MYSTERIOUS NELLIE KING: The So-Called Detective in the CityHer Side of the Story

Nellie King, the female detective, who is causing so much ado in the western press, arrived from Frankfort Wednesday evening, and a News representative interviewed her yesterday. She says she is twenty years old and has been connected with the Kingsford Detective Association of New York City, and that the article in the Minneapolis and Saint Paul papers saying that she had ran away from her home in Minneapolis is not true. My home, says she, is in New York City. I came west the 10th of last February in search of a valuable horse which had been stolen from a leading stock barn of New York City. The horse is a bay mare 12 hands high; six years old and has a record of 2:15, valued at $8,000. I found the horse well blanketed on the streets of Redfield, and I now have him in the city, but where he is no one but myself shall know. I will start with the horse for Chicago in a day or two, and from there I go to New York. At Frankfort, I saw a horse which I thought was the one I was in search of, and I demanded the same from the man driving it; he refused to give up the animal, and I drew my 38-caliber revolver, when he immediately obeyed. After a closer examination, I found the horse was not the one I was after and returned it. The papers got it that I drew a revolver on a young gentleman that came from Minneapolis or St. Paul with me, but that is a blank lie.

Miss King looks about 23 years old, has keen blue eyes and rather inclined to be good looking. She has a very determined manner but is of a nervous temperament. There is a deep mystery connected with the woman which has not yet been discovered, and judging from her shrewdness in language and manner, it will remain a mystery for some little time.

The Aberdeen Weekly News writer was prescient, as the mystery of Nellie King has endured for over 125 years. The puzzle over her identity and background has been a product of the scarcity of historical evidence, contemporary reporting inaccuracies and, most of all, Nellies own determination to mask her origins. As the following chapters trace her adult life, the mystery will appear to deepen with conflicting information, false leads and new aliases. Once all the clues are in hand, this text will then work toward a revelation of her secrets. This arrangement of facts is not artificially contrived; the solution to the enigma of Nellie King depends on evidence that accumulated through her life and culminates with disparate clues that surfaced near the end of her days.

Nellie Kings public record began ten days earlier than the Aberdeen newspaper account quoted above. On September 19, a lone bareback rider galloped along a wagon path that led to the settlement town of Frankfort, Dakota Territory. Much of the farmland the traveler passed was bare. Most of the spring wheat had been harvested, and sowing of the winter wheat crop was underway.

Each farm was a uniform tract mapped out by the federal governments 160-acre homesteading program. In order for a settler to gain full title to his lot, the grant needed to be occupied and actively worked for several years. Some of the settlers sod, log or framed houses were set close to the wagon road, and no doubt the rider drew curious stares from families engaged in their outdoor chores.

When large numbers of white settlers arrived in Dakota Territory in the late 1870s and early 1880s, the indigenous Yanktonnais and Santee Sioux (who had been driven westward from Minnesota and Wisconsin a generation earlier) were already constrained to small reservations in the region. Their main subsistence, the American bison, had been hunted to near extinction by market and sport hunters. Though the plains soil was rich, the climatic extremes often foiled cultivation practices that had proven successful elsewhere. The most viable option for land use proved to be the replacement of native grasses with wheat and other grains.

The settlement boom that began in the 1870s was sparked by a network of new railroads: the Chicago & North Western, the Milwaukee Road, the Great Northern, the Rock Island and others. The railways brought in the homesteaders and their supplies and took out their grain crops. Farmers were entirely dependent on their local railroad company. The railroads had the power to set transportation rates and, in collusion with favored grain wholesalers and lumber companies, offered communities little competitive choice. The railroads could cripple the agricultural economy of a town just by failing to route an adequate number of grain cars following a harvest.

Prior to harvest, a farmers entire seasonal crop could vanish due to drought, hail, extreme cold, locust plagues or flooding rains. Many homesteaders were in debt even before they plowed any ground in order to pay for their building supplies and farm equipment. They also had the expense of keeping livestock, since the sowing and harvesting was accomplished using the power of horses and oxen. The pressures on a family trying to maintain a homestead lot were enormous. By the late 1890s, the failure rate of single-family homesteads led to consolidation of lots and increased mechanization. Settler families had to be hardworking, with little leisure time or expendable income.

Settlement towns in eastern Dakota Territory did not resemble the freewheeling boomtowns inspired by the high-risk work and quick riches of the mining, lumber or cattle industries. There were no grand saloons or dance-hall brothelsthough the same vices did exist on a smaller scale. There were no resident rowdy cowboys, prospectors or lumberjacks. For the most part, these towns offered only essential services: rail stations, land offices, post offices, banks, general stores, farm equipment dealers, livestock exchanges and grain elevators. Professionals such as lawyers, doctors, dentists and midwives served the surrounding populace. The main social centers were churches and schools.

Next page