Taken together, the three essays are a reminder of the powerful influence Wisconsin has had on American historical writing. No one has better than Billington in brief compass captured the sense of the states cultural landscape after the Civil War. He gives us a picture of Turners Wisconsin that will ring true to anyone familiar with the states people and its life. Moreover, he explains how a youth from the backwoods with an inquiring mind could become a major figure in our history. Turners essay on The Significance of History indicates the intellectual integrity and imagination that characterized his approach to learning. It is also a vivid and healthy reminder of why the study of history should be a vital part of our educational system. Turner explains what the New History of the twentieth century is and how it should be studied if it is to be meaningful. The Significance of the Frontier in American History is a seminal work that should be read and reread by people who believe that history has meaning and importance to life. Partly because of its enormous impact and partly because it was the work of a young University of Wisconsin professor it deserves widespread distribution, especially at a time when many Americans have doubts about the nations values and goals. It remains an important essay for this generation.

I wish to thank Paul Hass and James P. Danky of the State Historical Society for encouraging me to write a new introduction for these essays and the Wisconsin Humanities Committee for making available to the people of Wisconsin this valued part of their heritage.

Introduction

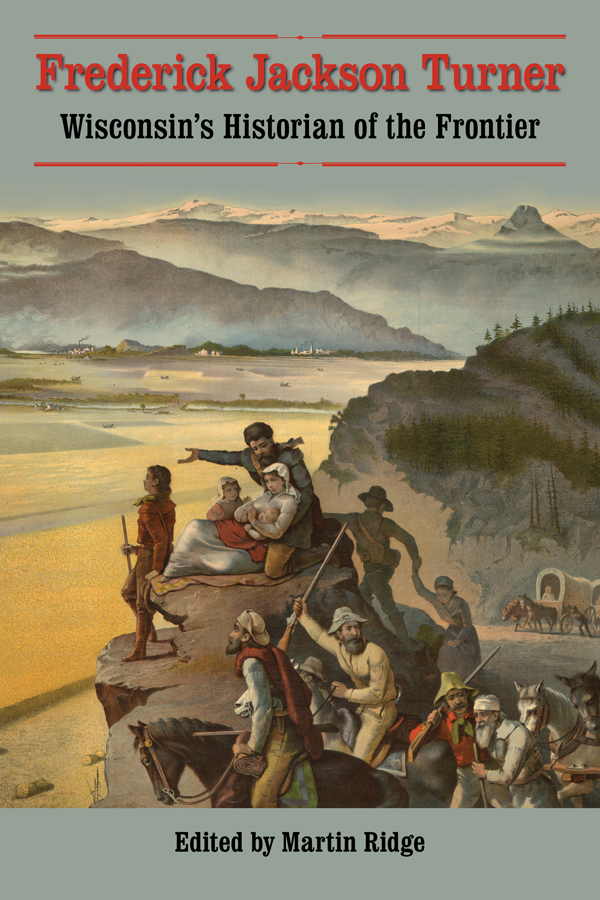

Martin Ridge

THERE IS LITTLE NEED to justify the publication of these several essays by and about Frederick Jackson Turner, Wisconsins most famous historian. He had a profound impact not only on his own generation of historians but also on subsequent thinkers. He was not the author of many books, but was a brilliant interpretative essayist at a time when many other American historians were doing the rudimentary groundwork in American history by editing documents and writing turgid monographs. He was also a leader in the struggle for the professionalization of history as a discipline and a rigorous opponent of amateurs. Turner had a profoundly humane view of the role that history could play in the education of the average citizen but a very jealous and compelling one when he argued that without the study of history Americans risked rearing a generation of statesmen without knowledge and a population without a sense of citizenship. He saw in the American frontiering experience a key to understanding our history.

That this collection of essays should begin with one by Ray Allen Billington is entirely appropriate, because he was this centurys foremost defender and interpreter of Frederick Jackson Turner as well as his biographer. Billington, like Turner, was Middle Westerner, a graduate of the University of Wisconsin, and a one-time journalist who eventually found history to be his first love. Billington, however, was not an early convert to frontier history. As a graduate student at Harvard, he was more interested in social and intellectual history; and he wrote his dissertation with Arthur Schlesinger, the dean of American cultural and intellectual historians. (Billington did audit a course with Frederick Merk, Turners loyal disciple, who had succeeded him at both Wisconsin and Harvard.)

Billington turned to the study of frontier history when a good friend, James Blaine Hedges, asked him to co-author a textbook on the subject. The book was not designed to be based on original research in the sources but it was to be deeply rooted in Turners idea of the frontier and was to incorporate the material in the most recently published scholarly books and articles on the subject. Hedges virtually dropped out of the project, completing only three chapters of the book, and Billington became increasingly immersed in writing the book that Turner would have written had he been the kind of historian who wrote books rather than essays.

From this introduction to frontier history, Billington moved to a study of Turners personal papers in the Huntington Library in San Marino, California; and there, reading Turners letters, unpublished essays, lectures, and notes, he fell under Turners spell and began a search for the sources of his ideas.

Despite the large number of books and articles that argued Turner was not an original thinker and his ideas could be traced to the research and writings of other scholars, including the Italian political economist Archille Loria, Billington believed that Turner could not have evolved his ideas had he not been reared on the edge of the frontier. It was not that his parents came from old-line New England Puritan stock or that his family had been part of a westering contingent that wandered into Wisconsin to make a new life; rather it was living in Portage, Wisconsin, after the Civil War that made him aware of the differences between frontier folk and activities and the people and practices of the American East and Europe.

Although Portage was no longer a frontier community but a bustling town of somewhat less than 5,000 souls when Turner was growing to manhood, the accounts of Indians, fur traders, trappers, and Irish lumbermen that made up the early history of the place still echoed in the streets. And Turner himself could recollect from his boyhood seeing Indians being shipped off to reservations, loggers tying up their rafts, and a dead manthe victim of a lynch mobleft hanging as an example. To live in Portage during these years was for Turner to feel a part of the great surge of national energy that was subduing, taming, and developing thecountry, as well as Americanizing immigrants. All of this Billington brilliantly tells in his essay Young Fred Turner, ending his narrative and analysis with episodes that embrace Turners life before he went to college. After reading Billingtons narrative, one is convinced that whatever Turner learned from books and manuscripts only confirmed what he absorbed from his personal experience with the people of Portage and from the brooks, lakes, and the piney landscape of Wisconsin.