B Y D A V I D M c G E E

................................................ 5

Raised, Delta Scarred ...................... 7

.............................................. 327

................... 330

.............................................. 336

........................................... 341

....................................... 343

................................................. 348

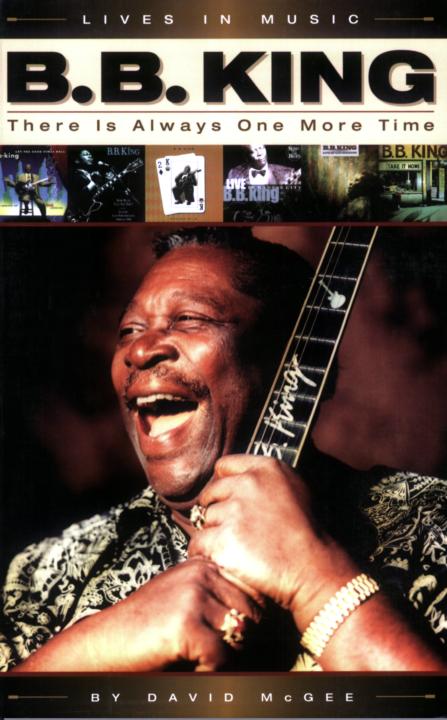

rom the beginning, B.B. King heard a bigger blues. A bolder and brassier, if not brasher, blues. A blues that by its big sound evoked the pentimento of life, even as it documented the observable rich patterns and near-palpable roiling emotions of the daily grind. A blues that sang, sang in celebration of our every breath, sang in celebration of life lived with a passion-a passion for love; a passion for friendship; a passion for companionship; a passion for truth and fair play in personal politics; a passion, it's true, for the revenge of living well; a passion for... passion.

rom the beginning, B.B. King heard a bigger blues. A bolder and brassier, if not brasher, blues. A blues that by its big sound evoked the pentimento of life, even as it documented the observable rich patterns and near-palpable roiling emotions of the daily grind. A blues that sang, sang in celebration of our every breath, sang in celebration of life lived with a passion-a passion for love; a passion for friendship; a passion for companionship; a passion for truth and fair play in personal politics; a passion, it's true, for the revenge of living well; a passion for... passion.

Born Riley B. King in Mississippi, to Nora Ella and Albert Lee King, the boy felt his soul stirred first by the spiritual messages of the gospel songs he sang in church every week. Then he was moved to make his own music after being transformed by the words and music of Blind Lemon Jefferson and Lonnie Johnson-the former being raw, rhythmically intricate, lyrically dark and brooding blues with a randy streak detailing aspects of the segregated world his audience knew well; the latter marked by its cool urbanity, stylistic diversity, and the artist's innovative guitar stylings-fluid, lyrical singlestring runs, unusual chordings, double-note harmonic passages-that had elevated the guitar to the forefront as a solo instrument. (Johnson could play country blues with breathtaking command, step into a small-combo or bigband context and deliver a well-observed slice of city life in a jazz setting, or caress a pop confection-be they his own compositions or covers of popular standards-with appealing, unassailable conviction.) Comforted by the sacred, young Riley's imagination was ignited by the secular, because it told a story he saw unfolding every day, either in the cotton fields or in the community. And somewhere between Blind Lemon Jefferson, Lonnie Johnson, and, later, the exuberant jump blues of Louis Jordan, between the hard life in the Mississippi Delta cotton fields and the joyful world of the Church of God in Christ, he found his own turf-seized it, cultivated it, contoured it so it remained fertile season after season, yielding, ultimately, impressive amounts of legal tender, but, more important, a richness of heart and soul that would form him as surely as the music he absorbed in his youth and reimagined in his adult life.

was born in the great Mississippi Delta, that part of America that someone called the most Southern place on earth. Born on September 16, 1925, on the bank of Blue Lake, between Indianola and Greenwood, near the tiny villages of Itta Bena and Berclair. Daddy was Albert Lee King and named me Riley B. The 'B' didn't stand for anything, but the 'Riley' was a combination. Daddy had lost a brother called Riley, but Daddy also drove a tractor for a white plantation owner named Jim O'Reilly. When Mama went into labor and Daddy went looking for a midwife, O'Reilly helped him find the right woman. O'Reilly was there when I was born and asked Daddy what he was calling his baby boy. Seeing that O'Reilly was a fair and good man, he wanted me to have his name. Years later, when I asked Daddy why he dropped the '0,' he said, "Cause you didn't look Irish.""

was born in the great Mississippi Delta, that part of America that someone called the most Southern place on earth. Born on September 16, 1925, on the bank of Blue Lake, between Indianola and Greenwood, near the tiny villages of Itta Bena and Berclair. Daddy was Albert Lee King and named me Riley B. The 'B' didn't stand for anything, but the 'Riley' was a combination. Daddy had lost a brother called Riley, but Daddy also drove a tractor for a white plantation owner named Jim O'Reilly. When Mama went into labor and Daddy went looking for a midwife, O'Reilly helped him find the right woman. O'Reilly was there when I was born and asked Daddy what he was calling his baby boy. Seeing that O'Reilly was a fair and good man, he wanted me to have his name. Years later, when I asked Daddy why he dropped the '0,' he said, "Cause you didn't look Irish.""

Such are B.B.'s fondest memories of his Daddy. Nora Ella and Albert Lee parted company in their son's youth, and years later B.B. would recall that Daddy "only comes into focus when I see him waving good-bye. He's standing still, but me and Mama are moving." Nora Ella took young Riley back to her family in Kilmichael, Mississippi, where various relatives worked on white-owned plantations and, more important, passed on hard-earned wisdom to the impressionable youngster. Crucial to his later development was the counsel of his great-grandmother, a former slave whom B.B. remembers talking about "the beginnings of the blues." She told him that singing helped get the field hands through the long days of picking, that "singing about your sadness unburdens your soul."' At the same time, though, the field hands were using the blues to send each other coded messages, warning of the boss's impending arrival. "Maybe you'd want to get out of his way or hide," B.B. says. "That was important for the women because the master could have anything he wanted. If he liked a woman, he could take her sexually. And the woman only had two choices: do what the master demands or kill herself. There was no in-between. The blues could warn you what was coming. I could see the blues was about survival."3

The blues was about survival.

That initial insight into the power of music would inform one of the most imposing bodies of musical work ever recorded by an American artist. It was a childhood lesson that stuck in a profound way. But his great-grandmother's wisdom was only the beginning of Riley B. King's education. "What mattered most in the Mississippi of my childhood was work," B.B. recalls! He toiled in cotton and corn fields, milked 20 cows a day (ten in the morning, ten at night) on Flake Cartledge's farm. After those morning milkings, he walked some three miles to the one-room schoolhouse that was home to kindergarten through grade 12, all taught by Luther Henson, "who had a powerful influence on my young brain."5 By his own admission, B.B., who was afflicted with a pronounced stutter, was an indifferent student ("I'd put myself near the bottom"6), but not without common sense, an innate intelligence, a curiosity about the world, and a mind ready to absorb his elders' instruction. Luther Henson gave him the blessing of hope, and demonstrated a spiritual resiliency Riley embraced as he cultivated dreams of a better life far from the Delta cotton fields.

rom the beginning, B.B. King heard a bigger blues. A bolder and brassier, if not brasher, blues. A blues that by its big sound evoked the pentimento of life, even as it documented the observable rich patterns and near-palpable roiling emotions of the daily grind. A blues that sang, sang in celebration of our every breath, sang in celebration of life lived with a passion-a passion for love; a passion for friendship; a passion for companionship; a passion for truth and fair play in personal politics; a passion, it's true, for the revenge of living well; a passion for... passion.

rom the beginning, B.B. King heard a bigger blues. A bolder and brassier, if not brasher, blues. A blues that by its big sound evoked the pentimento of life, even as it documented the observable rich patterns and near-palpable roiling emotions of the daily grind. A blues that sang, sang in celebration of our every breath, sang in celebration of life lived with a passion-a passion for love; a passion for friendship; a passion for companionship; a passion for truth and fair play in personal politics; a passion, it's true, for the revenge of living well; a passion for... passion.

was born in the great Mississippi Delta, that part of America that someone called the most Southern place on earth. Born on September 16, 1925, on the bank of Blue Lake, between Indianola and Greenwood, near the tiny villages of Itta Bena and Berclair. Daddy was Albert Lee King and named me Riley B. The 'B' didn't stand for anything, but the 'Riley' was a combination. Daddy had lost a brother called Riley, but Daddy also drove a tractor for a white plantation owner named Jim O'Reilly. When Mama went into labor and Daddy went looking for a midwife, O'Reilly helped him find the right woman. O'Reilly was there when I was born and asked Daddy what he was calling his baby boy. Seeing that O'Reilly was a fair and good man, he wanted me to have his name. Years later, when I asked Daddy why he dropped the '0,' he said, "Cause you didn't look Irish.""

was born in the great Mississippi Delta, that part of America that someone called the most Southern place on earth. Born on September 16, 1925, on the bank of Blue Lake, between Indianola and Greenwood, near the tiny villages of Itta Bena and Berclair. Daddy was Albert Lee King and named me Riley B. The 'B' didn't stand for anything, but the 'Riley' was a combination. Daddy had lost a brother called Riley, but Daddy also drove a tractor for a white plantation owner named Jim O'Reilly. When Mama went into labor and Daddy went looking for a midwife, O'Reilly helped him find the right woman. O'Reilly was there when I was born and asked Daddy what he was calling his baby boy. Seeing that O'Reilly was a fair and good man, he wanted me to have his name. Years later, when I asked Daddy why he dropped the '0,' he said, "Cause you didn't look Irish.""