Copyright Gabrielle Walker, 2007

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.hmhco.com

First published in Great Britain by Bloomsbury in 2007

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Walker, Gabrielle.

An ocean of air: why the wind blows and other mysteries of the atmosphere/Gabrielle Walker.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. AtmosphereHistory. 2. AirHistory. 3. ScienceHistory. I. Title.

QC855.W35 2007

551.509dc22 2006032359

ISBN 978-0-151-01124-7

e ISBN 978-0-547-53695-8

v3.1214

For Fred and Hubert

I adorn all the earth.

I am the breeze that nurtures all things green.

I encourage blossoms to flourish with ripening fruits.

I am led by the spirit to feed the purest streams.

I am the rain coming from the dew

That causes the grasses to laugh with the joy of life

Hildegard of Bingen,

TWELFTH-CENTURY ABBESS

Prologue

AUGUST 16, 1960 7 A.M.

TWENTY MILES ABOVE NEW MEXICO, Joe Kittinger was hanging in the sky. For eleven minutes he remained there, poised in an open gondola that twirled slowly beneath a vast helium balloon. Though it was long past sunrise, the air around was dark as midnight. Far below, where Earths surface curved away to the horizon, a glowing blue halo stood out against the blackness of space.

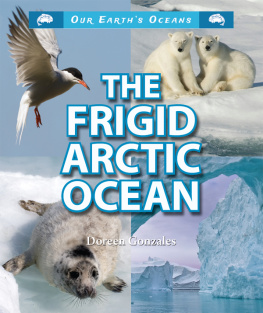

This glow was the atmosphere, the single greatest gift our planet possesses. Earths glorious blue color comes not from the oceans, but from the sky, and every astronaut who has seen that delicate halo has come back with the same tale: They couldnt believe how fragile it made Earth seem, and how beautiful.

Back on the surface, robbed of that lofty perspective, we are inclined to take our atmosphere for granted. Yet air is one of the most miraculous substances in the universe. Single-handedly, that thin blue line has transformed our planet from a barren lump of rock into a world full of life. And it is the only shield that stands between vulnerable earthlings and the deadly environment of space.

Kittinger, however, had journeyed beyond its protection. Up on the edge of space, the air was so tenuous that if his pressure suit failed he would die within minutes. First his saliva would bubble, then his eyes pop and his stomach swell, and finally his blood would boil. Despite all the risks he had taken as a test pilot for the U.S. Air Force, he had never been in greater danger.

Alone in his gondola, he was acutely aware of the menace. The near-vacuum seemed strangely substantial, like an enveloping layer of poison. The darkness rattled him, as did the curtain of clouds far below that were cutting off all views of home. He radioed to ground control. There is a hostile sky above me, he said. Man will never conquer space. He may live in it, but he will never conquer it.

He shuffled toward the door, weighed down with 150 pounds of survival gear, instruments, and cameras, and stood for a moment, his boots protruding slightly over the ledge. Several inches below his feet, a sign declared highest step in the world. He took a single breath of pure oxygen from within his tightly sealed helmet. Lord, take care of me now, he said. And then he jumped.

At first, Kittinger had no sense of falling. He could see the white swirls of storm clouds far below his feet, but they were growing no closer. The air around him was so thin that there was no sound or wind or any other clue that he was plunging through the most hostile environment a human being had ever faced. Spread-eagled in the sky, he felt almost serene. He could have been floating on a sea of nothingness.

Dangerous though the environment was, it was still protecting him. Lack of pressure isnt the only hazard in space; there is also a constant barrage of radiation, much of it from our own sun. Every day, along with the warmth and light that allow us to live on Earth, the sun sends out x-rays and ultraviolet light from the deadly end of its rainbow.

Thanks to our intervening sky, this radiation never reaches the ground. Fifty miles above Kittingers head, a few scarce atoms of air were acting as sentinels, intercepting and absorbing those lethal x-rays. In the process, these atoms were being ripped to shreds and heated to temperatures of 2,000 degrees. They form the ionosphere, a tenuous region of the atmosphere where electricity is king. Unseen from Earths surface, giant blue jets of fire leap up to this layer from the tops of thunderclouds, in bolts of reverse lightning. Here, meteorites from space are obliterated in the glorious blaze of light that we call shooting stars. They splatter the air with floating layers of metal that allow electric currents to swoop around the upper Earth. Radio broadcasts reflect from this charged surface as they bounce their way around the globe.

Farther up still, the air above Kittinger was facing an even more violent attackfrom a force known as the solar wind. Electrically charged jets of particles from the sun were barreling toward Earth at more than a million miles an hour, ready to strip away our atmosphere and send it streaming out behind the planet like the tail from a giant comet.

But to do so, it would first need to pass one of our staunchest defendersEarths magnetic field. On the surface we scarcely notice this field, except when it helpfully tugs compass needles into pointing north. But its arching influence extends tens of thousands of miles above us, and it forces the solar wind to part around it like water around a ships bow. Far above Kittingers head, those protective magnetic arcs were channeling the solar wind harmlessly away. The field is all but impenetrable, allowing just a few particles to leak into the polar regions, where they collide with the atmosphere to provide the dancing glows of the northern and southern lights.

Still, almost all our protective atmosphere lies within a few miles of the surface, and when Kittinger took that high-altitude leap of faith, most of it was beneath him. A few seconds into his fall, he kicked and twisted until he was facing upward. Now he could see the taut white sphere of his balloon shooting up into the darkness at a breakneck speed. This, Kittinger knew, was an illusion. The balloon was still floating gently where he had left it. He was the one falling down through the sky at close to the speed of sound.

Kittinger was tumbling now through another of our worlds vital protective shieldsthe ozone layer. All around him, any invisible ultraviolet rays that had slipped through the ionosphere were being soaked up by a diffuse cloud of invisible gas. Ozone is miraculous stuff. Near the ground it is sometimes created by lightning bolts or spark plugs. It smells like burning electrical wires and makes you choke. But high aloft it is both vigilant and resilient. Split asunder by ultraviolet rays, the ozone molecules around Kittinger were calmly re-forming. Like the burning bush encountered by Moses, they are constantly ablaze but never consumed.

Seventy thousand feet. Sixty thousand. Kittinger was now below the point where even a pinhole in his suit would have allowed his blood to boil off into space. But he had one last hazard to face: He had reached the coldest part of his descent, where the temperature had fallen to 98 degrees below zero and the heating elements in his suit mattered most.

Then there were clouds, and wind, and all the signs that Kittinger was finally approaching home. Forty thousand feet. Thirty thousand. He was about to drop past the altitude of Mount Everest. Any jet plane that happened to be flying nearby would see a man in a strange suit shooting past the window. The clouds he had seen from the gondola, blocking his view of home, were now rushing toward him. Though he knew they were only insubstantial water droplets, he still braced himself unconsciously for an impact, pulling his legs upward in anticipation. The moment he hit the clouds, his parachute opened and he knew he would live. Four minutes and thirty-seven seconds free fall! he said into his voice recorder. Ahhhhh boy!

Next page