SPECIAL THANKS: John Blake, Allie Collins and all at John Blake Publishing. Andy Bucklow, the Mail on Sunday. Alan Feltham, the Sun. Alex Butler, the Sunday Times. Bruce Waddell, the Daily Record. Dominic Turnbull, the Mail on Sunday. Zoe King, literary agent extraordinaire.

THANKS: Gary Edwards, Kevin Nicholls, Danny Bottono, Ben Felsenburg, Carole Theobald, Colin Forshaw, Ian Rondeau, Russell Forgham, Roy Stone, Tom Henderson Smith, Dave Morgan, David and Nicki Burgess, Denise Hannay, Pravina Patel, Meg Graham, Martin Creasy, Celee and Desmond Campbell, Angela, Frankie, Jude, Natalie, Barbara and Frank, Bob and Stephen, Gill, Lucy, Alex, Suzanne, Michael and William.

H e didnt sulk one little bit when the PE teacher informed him of his decision. Instead, the 13-year-old boy simply trotted away up the football pitch and determined that he would still be the bestat school today and, if his dream went to plan, in the professional game one special day in the not too distant future. Minutes later Gareth Bale went some way to proving that dream could become a reality as he was mobbed by his young team-mates after scoring with his right foot. Then, when he trooped off at the end of the match, he shook hands with the PE teacher who had banned him from using his left foot in that secondary school games lesson because that foot was so accomplished it was unfair.

After all, the way Gareth saw it the ban had brought an indirect bonus: it had paved the way for him to develop his weaker right foot. He would now make it his aim to strengthen it and become a complete all-rounderthat was the inspirational nature of the Welsh boy wonder from even such an early age.

We had to make up special rules for him, Gwyn Morris, the head of PE at Cardiffs Whitchurch High School and the man responsible for the ban, would say years later by way of explanation. In a normal game we had to limit him to playing one touch and he was never allowed to use his left foot. If we didnt make those rules he would have run through everyone, so it was the only way we could have an even game when he was involved.

Gareth Frank Bale was born on July 16, 1989, in Cardiff. His father, Frank, was a school caretaker (now retired) while mum Debbie was an operations manager with a law firm (a job she still holds to this day). His sister Vicky, who is three years older and now a primary school teacher in Wales, was also always a big supporter of him and his budding football career regularly travelling with Gareth and their parents from Cardiff to Southampton and back for training sessions from when he was 14.

Gareth attended Eglwys Newydd Primary School in Whitchurch and then moved up to the High School in the same essentially middle-class suburb, three miles north of Cardiff city centre. It was at Eglwys Newydd that, at the tender age of eight, his talent on the football pitch was first noted by those in the professional game.

Rod Ruddick, who helped run Southampton FCs satellite academy in Bath, spotted Gareth playing for a youth team called Cardiff Civil Service in a six-a-side tournament in Newport. Ruddick would later recall, Even then, at that age and despite his small size, I could tell Gareth was something special. It was small-sided mini football, six-a-side, but Gareth was head and shoulders above anyone else at the tournament. I used to attend various competitions in south Wales looking for talent, but never have I come across anyone quite like him.

Even back in those days, he would race past players down the left wing and score goals.

Ruddicks belief that Gareth would always have the pace to see off defenders was confirmed when he subsequently witnessed him finishing second in the Welsh national schools Under-11s 50m sprint.

Gareth was brought up in a family crazy about sport. He would say, My dad was always into sport and my mum was when she was younger, as was my sister. I kind of followed in the family footsteps. My dad played either rugby or football. His father also loved golf and his uncle Chris Pike showed Gareth the way forward towards his dreams by making a name for himself as a pro footballer with Cardiff City. At the age of three, Gareth would go to Ninian Park with dad Frank to see Chris play and Pike proved a fine role model, ending up Cardiffs top scorer in 1992, the season Gareth joined Frank on the terraces.

Gareth had a steady, stable upbringing in a solid family setting. He was a happy boy who spent most of his time kicking a ball about outside the familys modest three-bedroom terraced home.

Everything was very local in terms of friends and people we knew my best friend Ellis lived across the back from me. I remember my childhood spending time in the back garden or down at the park with my friends, playing football, messing around doing what all kids do, he would say.

He was interested in many sports he was also good at rugby, hockey and distance running but football was always his No. 1 priority. Gareth admitted, From literally the age of three, I just liked football. I always used to ask my dad to take me over to the park to practice it was always football for me and I was left-footed from the start I think.

He wasnt the best at the traditional school subjects but he was absolutely outstanding at football, easily the best in the school and the best Ive ever seen close up, said Carl Morgan, a fellow pupil. He was lucky in that he had such a supportive family; his dad was always at the side of the pitch urging him on and taking him here and there for matches. They were a very close family and anything Gareth needed he got, even though they werent well off.

By the age of 14 Gareth was also making trips to the Southampton academy itself, as well as their satellite centre in Bath. Dad Frank would accompany him around the country and Gareth would later admit the debt he owed to him, saying, My dads the one whos always been there; hes my hero, you could say. Even when he was working, hed do anything for me. Hes been the biggest influence in my life.

Even at such a tender age the search for perfection was apparent as Gareth spent hours alone working on his skills and technique on the training pitch long after the other boys had showered and left.

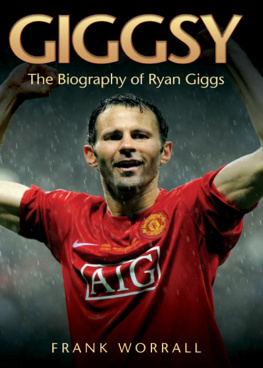

It was a trait that had been foreign to British footballers until six years earlier when Eric Cantona had arrived at Manchester United. Until 1996, the Brit pack would do their training and then head straight off home. But something stirred at Old Trafford when young men like Ryan Giggs and David Beckham saw the Frenchman Cantona still working alone as they jumped into their cars.

Beckham would later admit that it opened my eyes and he also began to delay his exit from training, working with and learning from the French master. Cantona would help David with his technique and encourage him to perfect his free kicks to great effect, as it would turn out.