Contents

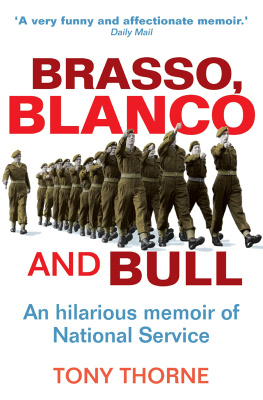

About the Book

From Barnardo boy to original virgin soldier; from apprentice journalist in Londons Fleet Street to famous novelist ...

At times funny, at times sad, but always honest and utterly compulsive, Leslie Thomass story is straight out of fiction. As an orphan, he picked his way through the rubble of post-war Britain and was sent on national service to the Far East. Later he became a Fleet Street reporter, with hilarious experiences to relate, and then became the bestselling author of The Virgin Soldiers the novel that, although scandalous in its day, is now recognised as a classic of its kind. He is also the creator of Dangerous Davies: The Last Detective, which has been adapted into a popular television series. In 2005, Leslie Thomas was awarded an OBE for services to literature.

With a new introduction for this edition, this is an amazing story, and Leslie Thomass magic touch brings it crackling to life with warmth, wit and humour.

About the Author

Born in Newport, Monmouthshire, in 1931, Leslie Thomas is the son of a sailor who was lost at sea in 1943. His boyhood in an orphanage is evoked in This Time Last Week, published in 1964. At sixteen, he became a reporter before going on to do his national service. He won worldwide acclaim with his bestselling novel The Virgin Soldiers. In 2005 he received the OBE for services to literature.

Also by Leslie Thomas

Fiction

The Virgin Soldiers

Orange Wednesday

The Love Beach

Come to the War

His Lordship

Onward Virgin Soldiers

Arthur McCann and All His Women

The Man with the Power

Tropic of Ruislip

Stand Up Virgin Soldiers

Dangerous Davies: The Last Detective

Bare Nell

Ormerods Landing

That Old Gang of Mine

The Magic Army

The Dearest and the Best

The Adventures of Goodnight and Loving

Dangerous in Love

Orders for New York

The Loves and Journeys of Revolving Jones

Arrivals and Departures

Dangerous by Moonlight

Running Away

The Dearest and the Best

Kensington Heights

Chloes Song

Dangerous Davies and the Lonely Heart

Other Times

Waiting for the Day

Dover Beach

Non Fiction

This Time Next Week

Some Lovely Islands

The Hidden Places of Britain

My World of Islands

I

STORIES RUN IN our family. My father, a wandering Welsh sailor, would come in with the tide, overflowing with yarns of ships and places, although as far as the places were concerned he often wrongly pronounced them and his knowledge of where they were located was not considerable. Well, he answered when once someone remarked on this. Its being a stoker, see. Im hardly on the deck from the time we sail to the time we tie up. How do I know where the ports are? All I know is Ive been there.

Similarly my mother responded to drama. Romance, tragedy, weepy songs, stirring hymns, disasters of the larger variety, weddings and especially funerals (Oh well, it was a nice day out wasnt it?) were the enjoyments of her life, to be retold often and with increasing exaggeration. Even my birth was a tall story. According to her it took place in the pricey privacy of a nursing home on Stow Hill, the highest point of Newport, Monmouthshire. This was an elevation in more ways than one because thereafter there were times when we could scarcely manage the cost of a bed, let alone a nursing home. There was a terrible thunder storm, my mother would relate, eyes beginning to glow, hands beginning to move. She had a throaty Barry Island voice. Terrible. Bangs and electric shocks all round the bed. Another, possibly pregnant, wait. And there was me, sitting up, see... singing! I could believe that. She had a faltering Welsh wail. She claimed she had sung Rock of Ages between thunder claps.

Not long ago I went up Stow Hill, a place of elderly large houses crowned by St Woolos Church, now a cathedral, and looked out over the dented roofs of Newport, my homeplace, a frontier town between England and Wales. There is a pub across the road from the churchyard and I wondered, as I sat in the bar, whether my father had drunk there. He probably had. There were few places he had missed.

My parents agreed on little but they would gladly call an armistice to verify each others tall stories. Like the one about the dog we had who one night came home, pleased enough, with a whole quiver of bones from the St Woolos burial ground. The road was being widened and he had taken advantage of the excavations to do some digging on his own account. In this story they actually lived (in residence according to my mother) on Stow Hill, possibly to be near the nursing home, but the first domicile of my memory was two rooms in Milner Street down by the murky and mucky River Usk, not far from the Transporter Bridge.

Now there was a wonder, the Transporter Bridge. We were told at school that it was one of only two in the country and a Frenchman was brought over specially to build it. I do not doubt that. It must have been the most uneconomic way of ever taking goods, people and vehicles from one side of a river to the other. In recent years the town discovered that it would cost more to demolish it than to keep it; so they kept it. It has two massive steel structures, one on each bank, like the towers you see above Texas oil wells but taller. Between the towers is a Meccano-set bridge and slung below this on cables, a platform pulled by hawsers from one side of the river to the other. For a boy it used to cost a penny to go across.

It was a childs delight to make that journey from bank to muddy bank of the Usk. I used to pretend I was going to another country. It was like travelling in the gondola of an airship, whirring slowly through space, the broad, black-tongued river curling below, little ships lying like dogs against its bank. On one side you could see the other more conventional town bridge and its traffic, the green cupola of the Technical College, with the wharves and warehouses and the stump of the ancient castle. Electric trams travelled in the distance, making sparks on dark days. On the other side of the Transporter, beyond the puffing steel works, the river yawned to the Bristol Channel. Misty miles away it seemed, the gateway, as my father pointed out to me in a scene reminiscent of the Boyhood of Raleigh, to the wide and amazing world. To look directly down below from the moving platform was to experience a delicious terror; snakes of thick water wriggled between slime coated by coaldust drifting from the Welsh valleys. It was legend that people had fallen or jumped and been sucked up by the hungry mud. I used to imagine them lying down deep, engulfed by the stuff... preserved. When the tide was up the river flowed strongly, but still foul and thick as if its bed were on top. One day, however, we saw a blithe sailing boat with scarlet sails on the moribund water and my mother burst into a loud and embarrassing chorus of a song called Red Sails In The Sunset. I had to ask her to stop and I could have only been four years old.

On another day she made a gallop for the travelling platform moments before its gate slammed, almost dragging me off the ground in her hurry. An avid funeral-spotter she had seen that the bridges cargo was nothing less than a cortge, the hearse and the two mourners cars standing dreadly beside a horse and cart and various pedestrians looking decently the other way. No such embarrassment discouraged my mam. We stood holding hands, neither of us being able to take our eyes from the glistening wood and shining handles of the coffin as the platform began its crossing. Unable to restrain herself any longer Mam approached the first mourning car and tapped politely but firmly on the closed window. A distraught and astonished face was framed when the glass had been lowered. Who is it? she enquired in a huge whisper jerking her head towards the hearse. The wind was blowing down the Usk and the platform was swaying.

Next page