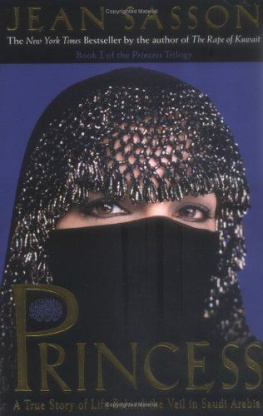

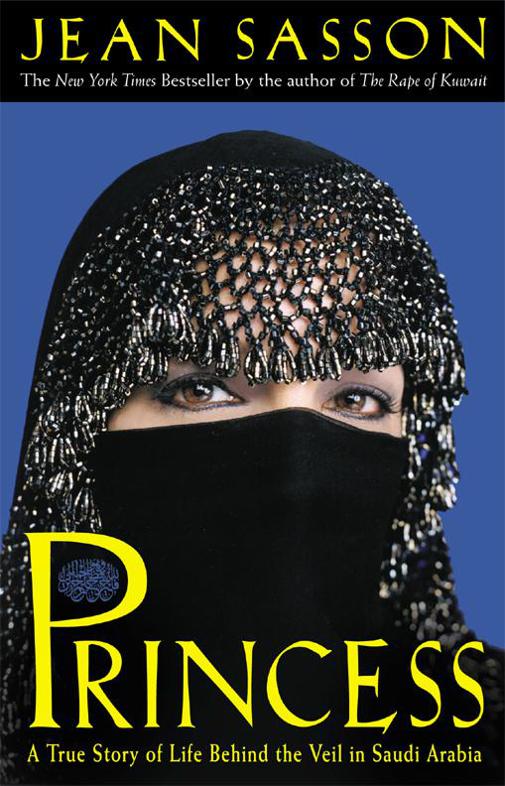

PRINCESS: A TRUE STORY OF LIFE BEHIND A VEIL IN SAUDI ARABIA INTRODUCTION

In a land were kings stil rule, I am a princess.

You must know me only as Sultana. I cannot reveal my true name for fear harm wil come to me and my family for what I am about to tel you. I am a Saudi princess, a member of the Royal Family of the House of Al Saud, the current rulers of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

As a woman in a land ruled by men, I cannot speak directly to you. I have requested an American friend and writer, Jean Sasson, to listen to me and then to tel my story.

I was born free, yet today I am in chains. Invisible, they were loosely draped and passed unnoticed until the age of understanding reduced my life to a narrow segment of fear.

No memories are left to me of my first four years. I suppose I laughed and played as al young children do, blissful y unaware that my value, due to the absence of a male organ, was of no significance in the land of my birth. To understand my life, you must know those who came before me.

We present-day Al Sauds date back six generations to the days of the early emirs of the Nadj, the Bedouin lands now part of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. These first Al Sauds were men whose dreams carried them no farther than the conquest of nearby desert lands and the adventures of night raids on neighboring tribes. In I89I, disaster struck when the Al Saud clan was defeated in battle and forced to flee the Nadj. Abdul Aziz, who would one day be my grandfather, was a child at this time. He barely survived the hardships of that desert flight. Later, he would recal how he burned with shame as his father ordered him to crawl into a large bag that was then slung over the saddle home of his camel. His sister, Nura, was cramped into another bag hanging from the other side of their fathers camel. Bitter that his youth prevented him from fighting to save his home, the angry young man peered from the bag as he swayed with the gait of the camel. It was a turning point in his young life, he would later recal , as he, humiliated by his familys defeat, watched the haunting beauty of his homeland disappear from view. After two years of nomadic desert travel, the family of Al Sauds found refuge in the country of Kuwait.

The life of a refugee was so distasteful to Abdul Aziz that he vowed from an early age to recapture the desert sands he had once cal ed home. So it was that in September I90I, twenty-five-year old Abdul Aziz returned to our land. On January I6, I902, after months of hardship, he and his men soundly defeated his enemies, the Rasheeds. In the years to fol ow, to ensure the loyalty of the desert tribes, Abdul Aziz married more than three hundred women, who in time produced more than fifty sons and eighty daughters.

The sons of his favorite wives held the honor of favored status; these sons, now grown, are at the very center of power in our land. No wife of Abdul Aziz was more loved than Hassa Sudairi. The sons of Hassa now head the combined forces of Al Sauds to rule the kingdom forged by their father.

Fahd, one of these sons, is now our king. Many sons and daughters married cousins of the prominent sections of our family such as the Al Turkis, Jiluwis, and Al Kabirs. The present-day princes from these unions are among influential Al Sauds.

Today, in I99I, our extended family consists of nearly twenty-one thousand members. Of this number, approximately one thousand are princes or princesses who are direct descendants of the great leader, King Abdul Aziz. I, Sultana, am one of these direct descendants.

|P a g e

PRINCESS: A TRUE STORY OF LIFE BEHIND A VEIL IN SAUDI ARABIA My first vivid memory is one of violence. When I was four years old, I was slapped across the face by my usual y gentle mother. Why? I had imitated my father in his prayers. Instead of praying to Makkah, I prayed to my six-year-old brother, Ali. I thought he was a god. How was I to know he was not? Thirty-two years later, I remember the sting of that slap and the beginning of questions in my mind: If my brother was not a god, why was he treated like one? In a family of ten daughters and one son, fear ruled our home: fear that cruel death would claim the one living male child; fear that no other sons would fol ow; fear that God had cursed our home with daughters. My mother feared each pregnancy, praying for a son, dreading a daughter. She bore one daughter after another until there were ten in al . My mothers worst fear came true when my father took another, younger wife for the purpose of giving him more precious sons. The new wife of promise presented him with three sons, al stil born, before he divorced her. Final y, though, with the fourth wife, my father became wealthy with sons. But my elder brother would always be the firstborn, and, as such, he ruled supreme. Like my sisters, I pretended to revere my brother, but I hated him as only the oppressed can hate. When my mother was twelve years old, she was married to my father. He was twenty. It was I946, the year after the great world war that interrupted oil production had ended.

Oil, the vital force of Saudi Arabia today, had not yet brought great wealth to my fathers family, the Al Sauds, but its impact on the family was felt in small ways.

The leaders of great nations had begun to pay homage to our king. The British Prime Minister, Winston Churchil , had presented King Abdul Aziz with a luxurious Rol s-Royce. Bright green, with a throne like back seat, the automobile sparkled like a jewel in the sun. Something about the automobile, as grand as it was, obviously disappointed the king, for upon inspection, he gave it to one of his favorite brothers, Abdul ah. Abdul ah, who was my fathers uncle and close friend, offered him this automobile for his honeymoon trip to Jeddah. He accepted, much to the delight of my mother, who had never ridden in an automobile. In I946-and dating back untold centuries-the camel was the usual mode of transportation in the Middle East. Three decades would pass before the average Saudi rode with comfort in an automobile, rather than astride a camel. Now, on their honeymoon, for seven days and nights, my parents happily crossed the desert trail to Jeddah.

Unfortunately, in my fathers haste to depart Riyadh, he had forgotten his tent; because of this oversight and the presence of several slaves, their marriage remained unconsummated until they arrived in Jeddah.

That dusty, exhausting trip was one of my mothers happiest memories. Forever after, she divided her life into "the time before the trip" and "the time after the trip." Once she told me that the trip had been the end of her youth, for she was too young to understand what lay ahead of her at the end of the long journey. Her parents had died in a fever epidemic, leaving her orphaned at the age of eight. She had been married at the age of twelve to an intense man fil ed with dark cruelties. She was ill-equipped to do little more in life than his bidding. After a brief stay in Jeddah, my parents returned to Riyadh, for it was there that the patriarchal family of the Al Sauds continued their dynasty. My father was a merciless man; as a predictable result, my mother was a melancholy woman. Their tragic union eventual y produced sixteen children, of whom eleven survived perilous childhood. Today, their ten female offspring live their lives control ed by the men to whom they are married. Their only surviving son, a prominent Saudi prince and businessman with four wives and numerous mistresses, leads a life of great promise and pleasure. From my reading, I know that most civilized successors of early cultures smile at the primitive ignorance of their ancestors. As civilization advances, the fear of freedom for the individual is overcome through enlightenment. Human society eagerly rushes to embrace knowledge and change.

Next page

![Sasson Jean - Jean P Sasson: [Princess 02]](/uploads/posts/book/233851/thumbs/sasson-jean-jean-p-sasson-princess-02.jpg)