First published in hardcover in the United States and the United Kingdom in 2016 by

Overlook Duckworth, Peter Mayer Publishers, Inc.

NEW YORK

141 Wooster Street

New York, NY 10012

www.overlookpress.com

For bulk and special sales please contact ,

or to write us at the above address.

LONDON

30 Calvin Street, London E1 6NW

T: 020 7490 7300

E:

www.ducknet.co.uk

For bulk and special sales please contact ,

or write to us at the above address.

2015 by John Spurling

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978-1-4683-1327-7

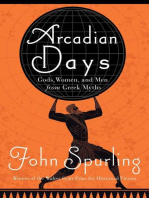

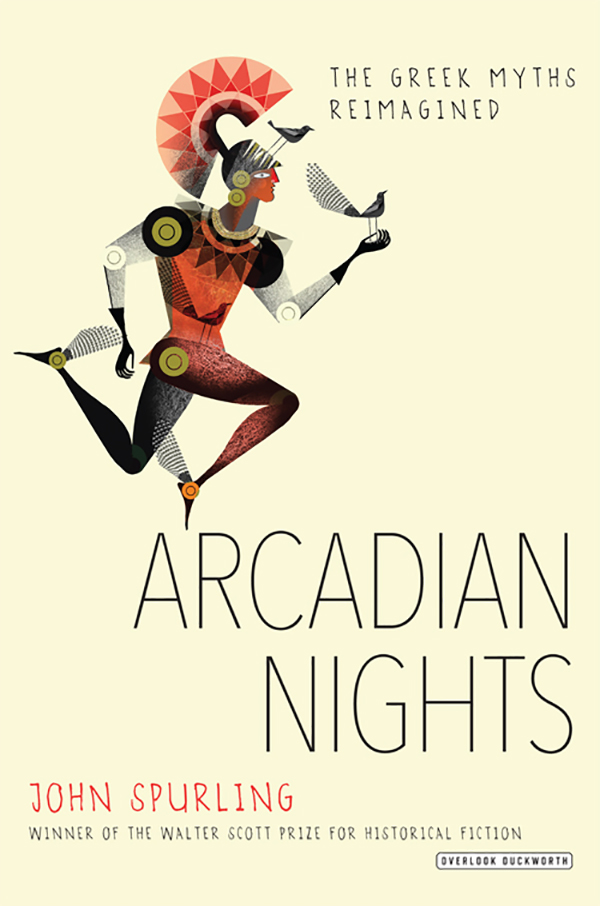

ARCADIAN NIGHTS

THE GREEK MYTHS REIMAGINED

JOHN SPURLING

T he classical Greek intellectual tradition pervades nearly every aspect of our modern Western civilization. Our logic and science, our philosophy, politics, literature, architecture, and art are all indebted to the ancient inhabitants of that small mountainous Mediterranean country. And the powerful myths of the Greeks, refined by Homer, Hesiod, Herodotus, and the great Greek dramatists, still resonate at the core of our culture.

Taking as his starting point many of the famous tourist sites in the Peloponnese, where the stories are set, John Spurling, winner of the 2015 Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction, freshly imagines key narratives from the Greek canon, including tales of the doomed house of Atreus (notably Agamemnon, leader of the Greeks at Troy, murdered by his wife in his palace bathroom); of the god Apollo; goddess Athene; Theseus, scourge of the Minotaur; the Twelve Labors of Heracles; and Perseus, rescuer of Andromeda.

In this vibrant, gripping and often grisly retelling of the Greek myths, stories of murder, power, revenge, love, and traumatic family relationships are made new again for our time with wit and relish by a gifted author. Spurling has added scene, dialogue, and context, while always staying true to the spirit of the original myth.

JOHN SPURLING is the author of the novels The Ten Thousand Things (winner of the 2015 Walter Scott prize for Historical Fiction), The Ragged End, After Zenda and A Book of Liszts. He is a prolific playwright, whose plays have been performed on television, radio and stage, including at the National Theatre. Spurling is also the author of two critical books on Graham Greenes novels and Samuel Becketts plays (with John Fletcher), has been a frequent reviewer for newspapers, magazines and BBC Radio, and was for twelve years the art critic of The New Statesman. He lives in London and Arcadia, Greece, and is married to the biographer Hilary Spurling.

In memory of my grandfather, J.C. Stobart,

who died before I was born,

and my grandmother, Molly Stobart,

who taught me to admire him and share his love of Greece.

I believe that our art and literature has by this time absorbed and assimilated what Greece had to teach, and that our roots are so entwined with the soil of Greek culture that we can never lose the taste of it as long as books are read and pictures painted.

from the introduction to J.C. Stobarts

The Glory That Was Greece (1911)

1. The Greek language has no letter c or diphthong ae, which come from Latin. Greek uses k and ai. For familiar names, such as Arcadia, Clytemnestra, Mycenae, I have used the Latin spelling, but for less familiar ones, the Greek. Herakles is the main exception, since the Roman Hercules is a composite figure, partly derived from the Greek hero, partly based on an old Italian deity.

The word Greek itself is, of course, a Latin usage, probably derived from the tribe of the Graeci who inhabited the north-western coast of Greece and were the first Greeks encountered by the Romans. The ancient Greeks called themselves Hellenes and their country Hellas, while modern Greeks, dropping the aspirate, call themselves llenes (three syllables with the accent on the first and a long e in the second) and their country Ellda.

The long e at the end of Greek names such as Athene, Antiope, Hippolyte, should always be sounded.

2. Human kind, said T.S. Eliot, cannot bear very much reality, and their myths cannot bear very much real time. For example: Pelops and his bride Hippodameia seem to be contemporary with Perseus, the great-grandfather of Herakles; Herakles is contemporary with Theseus; Theseus marries the daughter of King Minos; yet Pelops son Atreus, who should be at least two generations senior to Theseus, marries Minos granddaughter.

Ti na knoume; pause for no answer Den peirzei. (What are we to do? It doesnt matter.) Our neighbour in Arcadia rounds off her conversations over the fence with these useful phrases. They might come straight out of a Greek tragedy by Aeschylus or Sophocles, the hand-wringing words of a Chorus of old men or women contemplating the catastrophic downfall of Agamemnon or Oedipus, and they apply equally well to the long, rocky history of Greece. From ancient times it has been a story of foreign invasions, wars between city-states, venal demagoguery playing on popular gullibility, military dictatorships, civil war. Romans, Slavs, Venetians, Franks, Byzantines, Turks, Germans and Italians have come and gone. Just over a century ago my grandfather, J.C. Stobart, published his history of Greek culture, The Glory That Was Greece, and remarked in his introduction:

The traveller is struck with the small scale of Greek geography. From your hotel window in Athens you can see hill-tops in the heart of the Peloponnese. In that radiant sea-air the Greeks of old learnt to see things clearly. They could live, as Greeks still live, a simple, temperate life the modern Greek still reminds us of his predecessors as we know them in ancient literature. He is still restless, talkative, subtle and inquisitive, eager for liberty without the sense of discipline which liberty requires, contemptuous of strangers and jealous of his neighbour.

Now, as I write, the cosy embrace of the European common currency has turned into a strangling squeeze of impossible debt, austerity and looming economic collapse unless the Greeks can meet the terms and make the sacrifices demanded by the Eurocrats and in particular the Germans (the Greeks most recent invaders).

But whatever the hardships in the cities, where a large proportion of the population works for the government, the village people here in the Peloponnese go on much as they have for millennia. Their life was always hard and still is based on their olive trees, a few goats, a donkey, chickens, and home-grown fruit and vegetables. True, they now have electricity, to which the government adds tax probably the only way it can be easily collected from people who view the state chiefly as a source of unwelcome interference with their family-centred life and piped water, though some, including our neighbour, have gone back recently to using the well behind our house. They still bake their bread in outside bread-ovens, wash their clothes and cook their meals over open fires in the courtyards and warm themselves in winter at the fireplaces built into the back of the houses, their fuel being the branches they prune from their olive trees after gathering the olives in January. But these days, of course, since most of the villagers are old their children having migrated in better times to easier lives in the cities they have pensions, so long as the government can contrive to pay them.