The many sponsors and helpers who made Everest 1988 possible are acknowledged in Appendix I, but I would like here to thank all the people who gave so much invaluable help in the preparation of this book:

Lord Hunt for giving me the chance to go to Everest and writing a foreword to the book. Ed, Paul, Robert, Joe, Mimi, Pasang, Kasang and all the members of the expedition support team, for being such good companions and making this book possible.

Robert Anderson, Wendy Davis, Rosie Grieves-Cook, Elisabeth Hawley, Charles Houston, Annabel Huxley, Peter Lloyd, Vivienne Schuster, Ann Venables, Cangy Venables, and Isobel Walder for all their encouragement and valuable criticism of the manuscript.

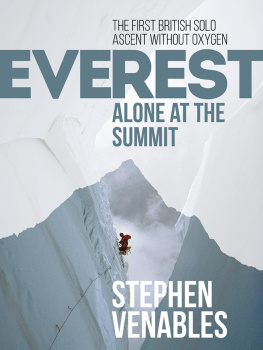

Margaret Body, my editor, for giving me so much encouragement, keeping me to deadlines and adding the finishing touches with her customary skill. Alec Spark for drawing the maps and diagrams; Lawrence Back and Trevor Spooner for designing the book; Sylvia Mitchell for black and white prints. Joseph Blackburn and Ed Webster for allowing me to use some of their superb expedition photographs. Mike Jones for the black and white photograph on the dust jacket, and Sam Farr for a promotional photograph. All photography in the book is courtesy of Eastman Kodak and Duggal Color Projects. All uncredited photographs were taken by the author.

BY LORD HUNT OF LLANFAIR WATERDINE

On an evening in October 1987, I received a telephone call from New York. A persuasive feminine voice informed me that an expedition was being organised in the United States to celebrate the thirty-fifth anniversary of the first ascent of Everest: Everest 88. Ed Hillary and Tenzing Norgays sons, Peter and Norbu, had agreed to join the party; the caller, Wendy Davis, invited me, on behalf of the organisers, to accept the title of Honorary Expedition Leader.

I confess to having felt chuffed by this accolade. The title was new in my experience. For all its symbolic, and possible public relations connotation, it sounded less senile than that of Patron, to which I was all too well accustomed. Anyway, it would have been churlish to refuse. But our expedition in 1953 had been organised in Britain; its members were mainly British mountaineers. I felt that at least one of these latter-day challengers of Everest should be a true Briton, and I said as much to the disembodied voice at the end of the transatlantic line.

A week or two later I met Robert Anderson, the Expedition Leader, during his stop-over in London on his way between his work in New Zealand and his home in the States. I suggested that he should invite a leading British climber to join his party so as to give substance to the notional connection between the expeditions of 1953 and 1988. I suggested the name of Stephen Venables and Robert agreed to write to him. Little did I realise what would ensue from that part of our conversation.

Robert also told me something of his plan to force a new route up the Kangshung Face of the mountain, further to the left of the bold line which had marked the first ascent of that face, achieved four years earlier by another American expedition. He showed me a very indifferent photograph, adding a throw-away comment: I think we can use this buttress, which will take us directly to the South Col. As his strictly honorary associate I expressed admiration, but suppressed my astonishment. For an old-stager like myself, it was indeed difficult to credit the audacity of such a hypothetical venture, which purported to follow a line to all intents and purposes as yet unseen, with a team of no more than four or five companions, and without oxygen.

My mind flew back to 25 May 1953, when I had looked down the Kangshung Face during a stroll, at 26,000 feet, across the South Col. Charles Evans, Tom Bourdillon and I were on our way up the mountain, which at that time had never been climbed. As I peered down the steep snow slopes plunging towards the brink of a tremendous precipice, until my eyes came to rest on the Kangshung Glacier 7,000 feet below me, I remember very clearly saying to myself: This will never be climbed. Such were the perceptions of what was impossible to mountaineers of my generation at that time; beyond which, even in our dreams, we did not dare to venture.

The ascent of Everest is nowadays a commonplace event. But Everest 88 is a story which will be told with a sense of wonder for years to come. It is remarkable for the skill required to scale the rampart of rock and ice which defends access to those long steep slopes leading upwards to the South Col, down which my eyes had travelled all those years ago. It is a story of courage and commitment by four climbers, with no reserves to call on in case of accident or illness, who, without resort to oxygen, overcame the combined problems of vertical rock and ice, handicapped by the effects of high altitude.

Even among such exceptional men, the performance of Stephen Venables was outstanding. From the South Col to the summit and, until he rejoined his companions after surviving a night out at over 27,000 feet on the South-East Ridge, he was on his own; his stamina and his will power somehow kept him going, despite his state of exhaustion after the long days of strain which the climbers had already endured in reaching the Col. I know of no finer example in mountaineering, of mind triumphing over matter.

But for me, the most gripping part of the story lies in the escape from the mountain. Extraordinary tales abound of human survival against the odds set by nature or circumstance; this ranks with the most remarkable among the ordeals from which men or women have returned alive. With some personal experiences of difficult retreats from high mountains, I can appreciate the anxiety, the tension, the exhaustion and near despair which those men experienced, as they fought their way down the Kangshung Face, severely frostbitten, dehydrated and without food, their tents and sleeping bags abandoned, losing trace of their fixed ropes, losing touch with one another. Climbers are proverbially prone to understatement, but Stephen Venables has done his readers a good service by writing himself into this story; by laying bare his feelings as he made his desperate way up and down Everest.