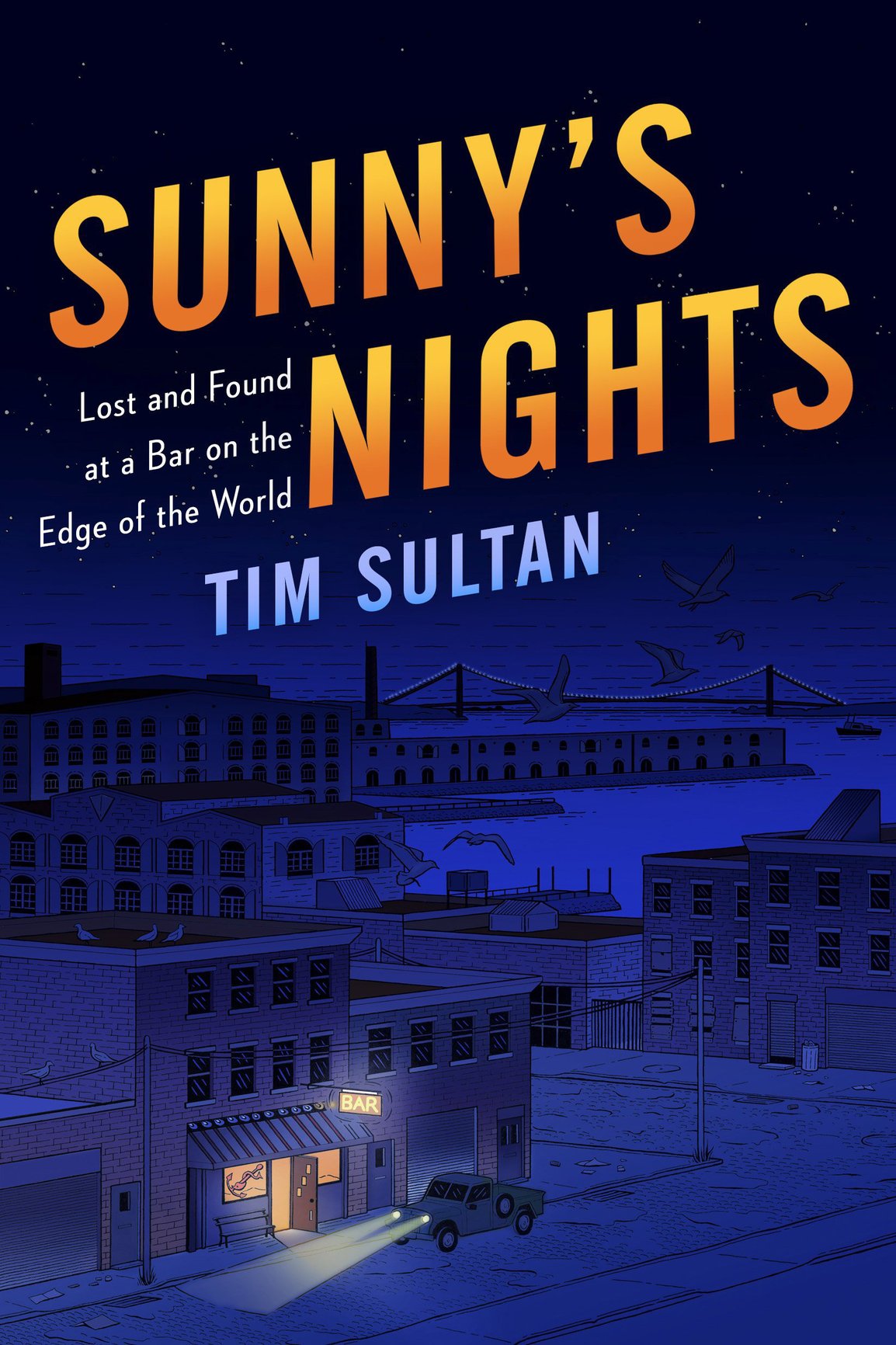

Copyright 2016 by Tim Sultan

Map copyright 2015 by David Lindroth, Inc.

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

R ANDOM H OUSE and the H OUSE colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to Hal Leonard Corporation for permission to reprint an excerpt from Rainy Night in Georgia, words and music by Tony Joe White, copyright 1969 (renewed 1997) by TEMI Combine Inc. All rights controlled by Combine Music Corp. and administered by EMI Blackwood Music Inc. Excerpt from Walk on the Wild Side, words and music by Lou Reed, copyright 1972 by Oakfield Avenue Music Ltd. All rights controlled and administered by EMI Music Publishing Ltd. All rights reserved. International Copyright Secured. Used by permission of Hal Leonard Corporation.

Photograph on courtesy of Jason Elias.

L IBRARY OF C ONGRESS C ATALOGING-IN- P UBLICATION D ATA

Sultan, Tim.

Sunnys nights : lost and found at a bar on the edge of the world / by Tim Sultan.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-4000-6727-5 ISBN 978-0-8129-8848-2 (ebook)

1. Sultan, Tim. 2. BartendersNew York (State)New YorkBiography. 3. BartendingNew York (State)New York. 4. Red Hook (N.Y.)Social life and customs. 5. Brooklyn (New York, N.Y.)Social life and customs. I. Title.

TX950.5.S85S85 2016

641.87'409747dc23

2015019985

eBook ISBN9780812988482

randomhousebooks.com

Book design by Susan Turner, adapted for ebook

Cover design: Caroline Teagle

Cover illustration: Stuart Patience

v4.1

ep

Contents

1

Antonio

T here is a corner turned, a direction taken. There is a door opened in everyones history that they can identify as the moment life, for better or worse, took a different course. Eve bit an apple. Dante saw Beatrice. Jack met Neal. For me, that corner, that direction, that door appeared late in the winter of 1995. The place was Red Hook, Brooklyn, the hour late, the mood desolate. I had gone to the nights last showing of Woody Allens Bullets Over Broadway and while driving home from the theater, mulling over the movie, I had half-absentmindedly continued straight where I usually took a left, slipping beneath an overpass and entering a neighborhood I knew only by its forbidding reputation. There were no other cars and no people and long stretches of shadow between the streetlamps. I drove on. Deliberately getting lost had been a pastime of mine since early childhood. I was raised by parents who only asked that I be home before sundown. By adolescence, I had lost my bearings in Laotian rice paddies, German forests, and a West African city where the practice of naming streets had not yet been widely adopted. In college one autumn, I courted a woman by inventing a game in which one of us would close our eyes and pretend to be blind, while the other made believe they were mute, and the mute person would lead the blind one by the hand on late-evening ambles through professors backyards and frosty Ohio pastures. By winter, we could have written dissertations on the merits of disorientation but we merely fell in love instead.

That Friday night in Red Hook I was twenty-seven years old, and again I found myself taking left and right turns seemingly at random, unsure whether I was sightseeing or soul-searching. A succession of low-slung industrial warehouses and towering fuel tanks gave way to darkened fields and from them the silhouette of an enormous building rose up, as still and monstrous as a pyramid. Bare trees bordering the road were the only living beings in sight. More turns. The pavement soon gave way to cobblestones and I slowed the car to a walking pace. Another building, vaguely Georgian, came into view. Its doorways and arched windows were sealed with bricks giving it the look of an asylum or prison or school, irrevocably shuttered. I deciphered white letters near the top: Shipyards Corporation.

Other lone structures appeared and melted away in my headlamps. I continued straight until I could go straight no farther. I had come to another corner. Conover Street, read the sign. Ahead, behind a rusty gate, stretched a barren lot and beyond that the water of the harbor shimmered faintly. To my right stood several satellite dishes, so immense they seemed capable of beaming their messages not only to New Jersey but to new planets. To the left more signs appeared in the gloom, one profoundly weird (Animal Hair Manufacturing Company) and the other weirdly spare (Bar). I pulled over and turned off the engine. I looked up and down the cobblestone street. There was no movement, no sound. I was alone and the sense of solitude that descended on me was as absolute as that usually only found in dreams. I wavered but a few moments before getting out of my car. Where bars were concerned, my spirit of inquiry always seemed to prevail over a sense of caution. I paused at the first building. Animal Hair Manufacturing Company. What could it mean? I walked on toward the next sign. Bar. I knew of a bar called the No Name Bar but I had never seen a bar that literally had no name. I had come to a place, it seemed, where the world was returning to its most elemental properties.

I took a few more tentative steps until I stood beneath one of two faded brown awnings. In between was a simple wooden door containing three peephole windows ascending from left to right as though to accommodate lookouts of varying heights. Two more storefront windows on either side of the door emanated a faint light and in this glow I could see a wooden ship and a black-and-white photograph of a sailor from an earlier generation resting on a ledge inside. The picture might have been taken during the Second World War.

I considered the forlornness of the area and of the night. I had entered a lot of bars in my life and rarely with hesitation. An early bloomer of a sort, I had my first tavern beer at fourteen and I graduated high school with the inglorious honor of being voted by my classmates as the student most likely to be found not in a barthat distinction went to my best friendbut under a bar. While I had gotten dissipation out of my system by the time I was an adult, I still knew my way around bars in the way a person raised on a farm never forgets how to cross a livestock yard. I reached forward and pulled open the door and stepped inside. Every one of the two dozen faces in the room was turned toward me. Pale faces, male faces, their attention to my entrance so complete, I might as well have burst into act I, scene 2 at the Delacorte. It was too late to turn around and exit stage left without feeling the fool. And so, I let the door softly close behind me.

In the brief time it took for my eyes to adjust to the dim light, I realized that the collective gaze was directed not at me but a movie screen that hung to the left of the door. A projector hummed in the rear of the room, its beam cutting through the gloom like a locomotive headlight. On the screen, opening credits were just beginning to appear. Martha Graham. Aaron Copland. Isamu Noguchi. Soon dancers in pioneer dress were swirling in black and white. Tinny classical music played. To the right, stools lined the bar. I slid onto the third one in and swiveled toward the screen. Among the several scenarios Id considered moments before as I had paused on the stoop outsidemost involving a roomful of repeat offenders as glad to see me as their parole officersa collection of men quietly smoking and watching a classic of modern dance had not been one of them. Encouraged, I waved to a figure leaning back against a counter behind the bar and, in a low voice, asked for a beer.