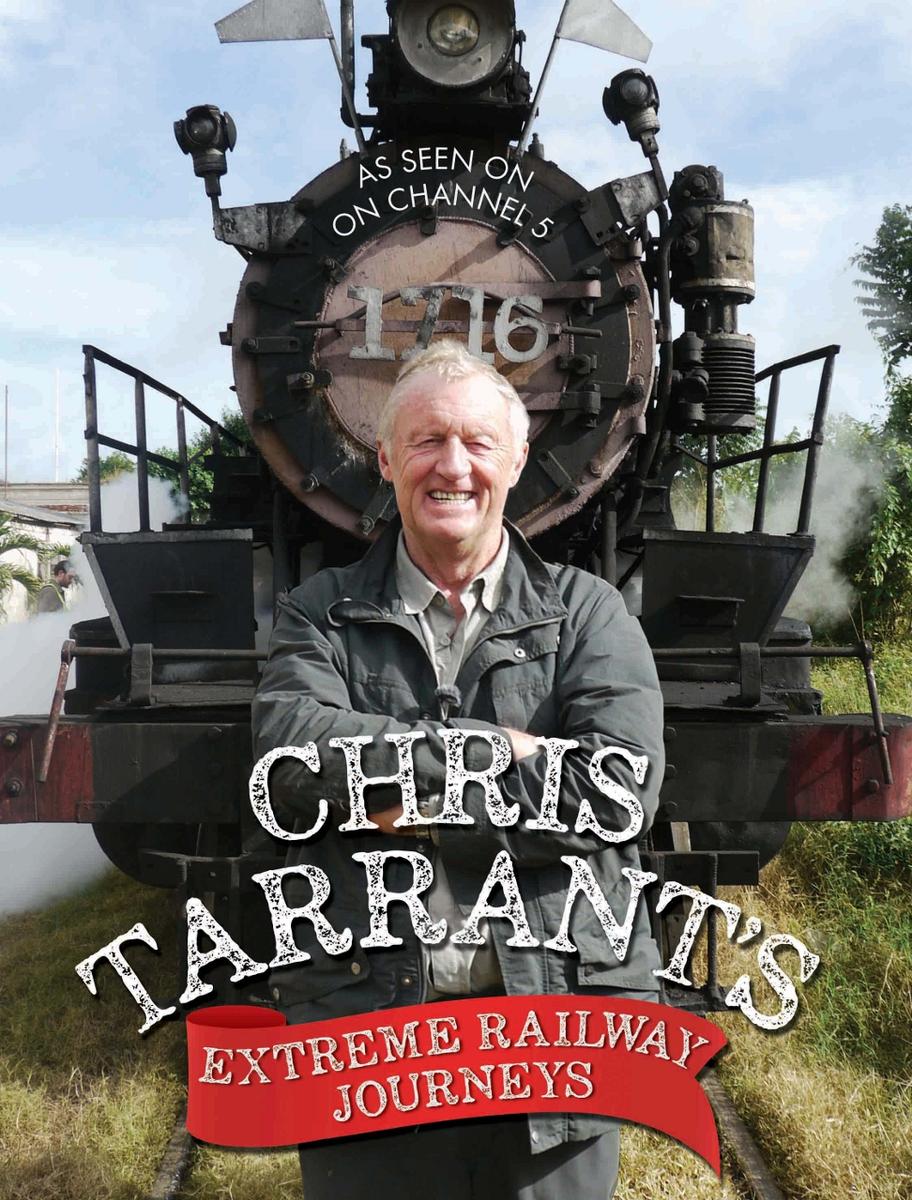

I was never a train spotter, even though we lived close to the old Great Western line in the heyday of steam. I used to see the real spotters, though, happily spotting away on the end of the platform at Reading Central, but they seemed to me to be rather a strange breed, wearing sandals and with their trouser-bottoms rolled up.

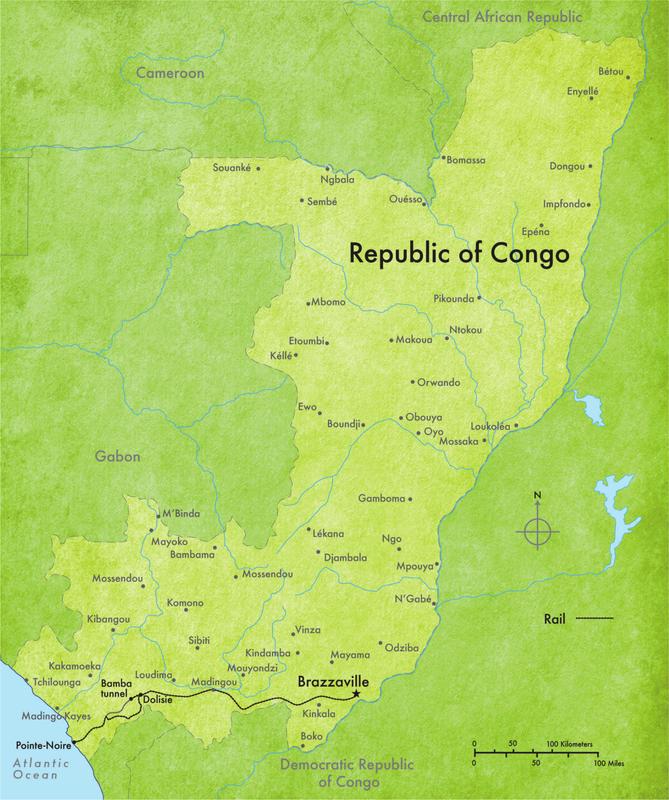

It was not the trains but the actual railways that fascinated me, particularly in remote countries with exotic-sounding names like Russia, Alaska, India and Japan. I knew that often, in wild areas of the planet where there were simply no roads, the railways were the only real link for whole populations. I just loved all the stories of the men who had the vision to build the first railways where no one thought it possible, to follow their own often ridiculed engineering plan and see it through, although often, tragically, with a large loss of life.

I was really looking forward to getting started on my first programme of what was a brand-new series. I have to admit that my enthusiasm was dampened when I was told that the first place we were going to visit with our film crew was the Congo.

Isnt it one of the most dangerous places in the world? I had the temerity to ask in our first production meeting.

Were going to the Republic of the Congo, I was told, not the Democratic Republic of Congo; DCR is the really bad one.

Oh, right I said, not reassured at all by this explanation of degrees of badness and really, really badness. I thought to myself, Why couldnt we go somewhere not bad at all, somewhere nice and safe? But, then again, I supposed the series was entitled Extreme Railways rather than Nice and Safe Railways.

Actually, I was kidnapped there last time, added Sam, our mad, Irish cameraman, by a load of big, scary, teenage kids with Kalashnikovs It was really frightening actually; just me and my producer whos a bit of a wimp. They bundled us into their car. Luckily, we got stopped at a police checkpoint so we made a run for it. He grinned manically and continued. We were both expecting a bullet in the back all the time, but they were just too busy shouting at each other. Lucky. eh?

Yes I said, really lucky, thinking, What the hell have I talked myself into?

Roz, our director, said she was due to fly out the next day on a reccy. I said, OK, clever clogs, if you get back in one piece well go and film it. If you dont, well go somewhere else maybe Monaco or Rome. Or even Swindon.

I assumed Id never ever see her again, so when she had the audacity to reappear beaming happily, still in one piece, about ten days later, I thought, Oh, sod it. OK, I said, Congo here I come

After a really scary Air France flight through central Africa (will somebody please tell me what the hell clear air turbulence is? Whatever it is God, it freaks me out!), we landed bouncily but happy to be on the ground at Pointe-Noire, one of the biggest ports in West Africa, where our first extreme journey was to begin.

Passing through Passport Control to enter the country of Congo was predictably chaotic but this was to be the pattern for the next few weeks. Lots and lots of incomprehensible bureaucracy and lots of men in big hats and uniforms who did a lot of shouting, but didnt actually seem to have any idea of what was supposed to be going on.

Standing in a queue of shouting people waving passports and being sent repeatedly to the back was daunting enough, especially with a film crew and mountains of very expensive camera gear, but the queue for yellow fever documentation was even longer and much more heavily policed. Luckily, I had all my jabs and certificates up to date, but there was certainly no messing with the Congolese authorities. If you hadnt got proof of current yellow fever inoculations you would be either pointed very roughly towards the queue for the next flight out or much much more frighteningly you would be taken by one of three men in white coats holding up syringes into a little tent and given your yellow fever vaccination jab on the spot. Thank God they accepted my paperwork, as absolutely nothing would have induced me to risk one of their horribly blunt-looking needles.

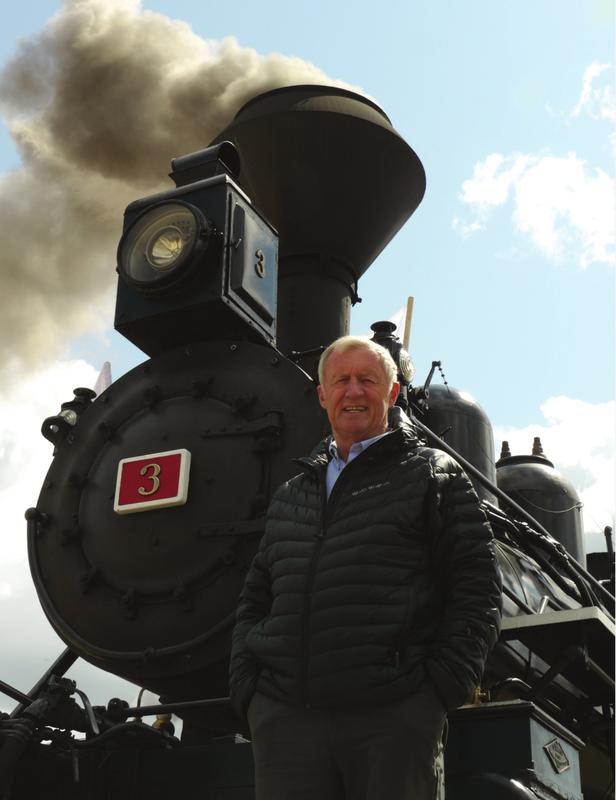

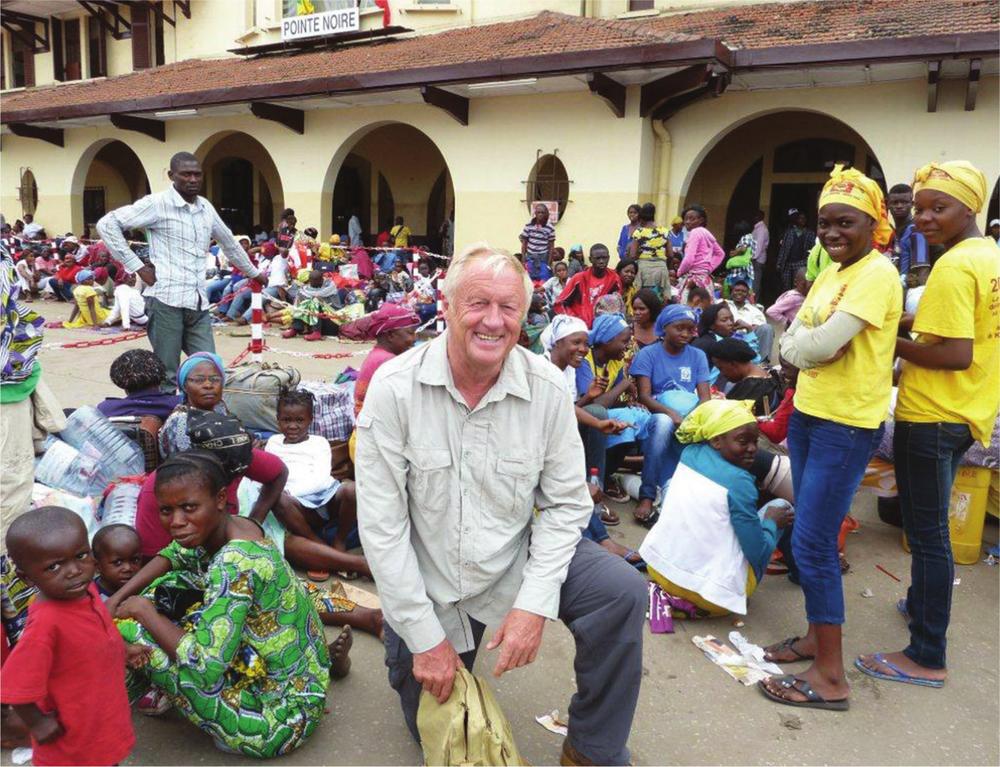

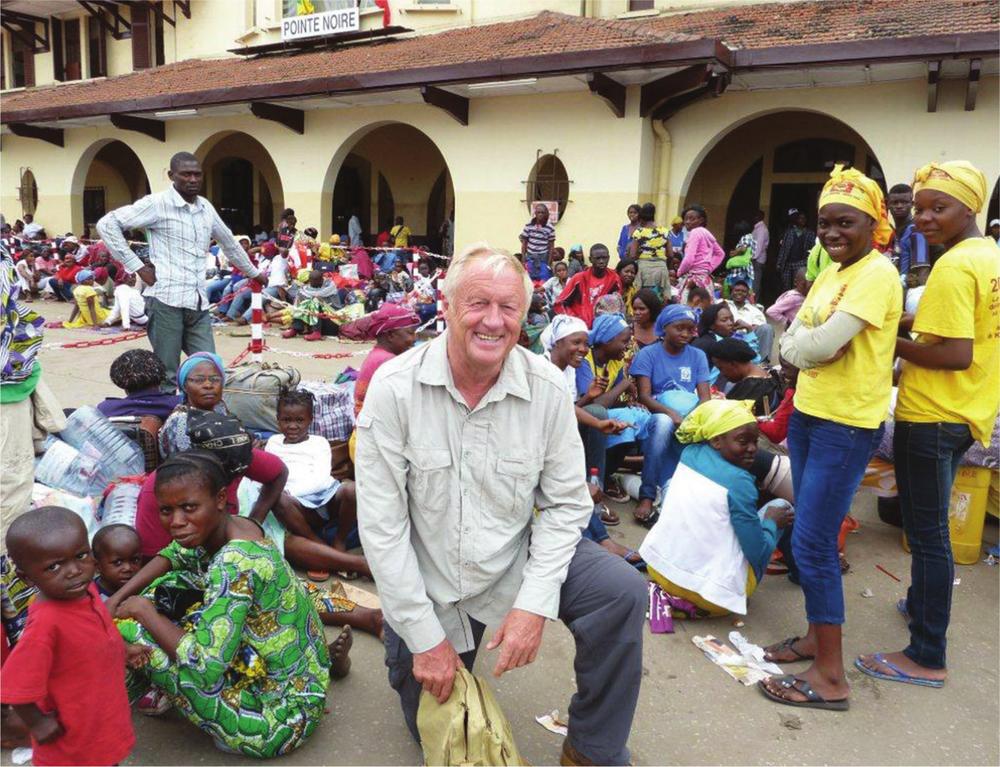

We spent the night in a hotel, supposedly one of Pointe-Noires finest but not so much five-star as AA-one-spanner. We found our way to the big main station actually the only station in town, to board the 11 am Congo Ocean Railway train to Brazzaville, the countrys capital. The station was unlike anywhere I had ever seen on earth, there was no departure board, nor any visible information of any sort, and seemingly nobody to ask. But there were literally thousands of men, women, children, tiny babies, dogs and a good number of bewildered looking goats, all seemingly waiting for the 11 am train. I had to produce my passport yet again to buy my ticket, but that seemed to guarantee that I would be on the COR express to go racing across the Congo to the capital.

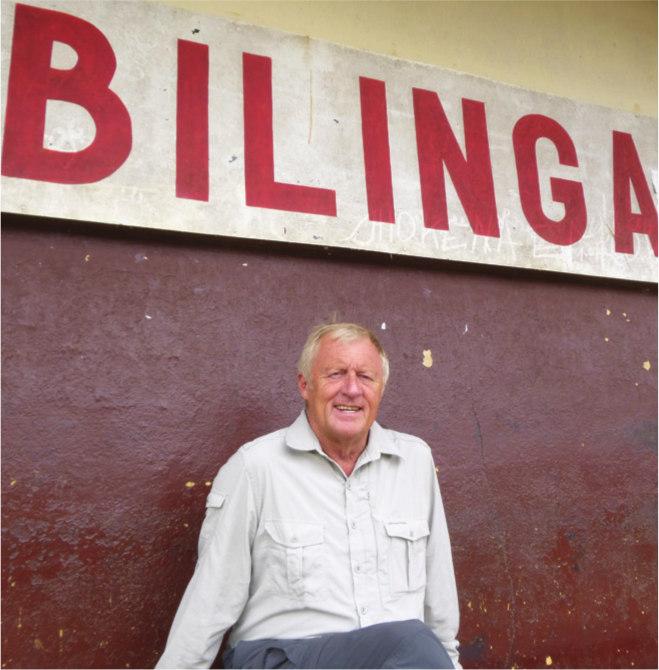

At the station at the start of the big wait for the only train out of town.

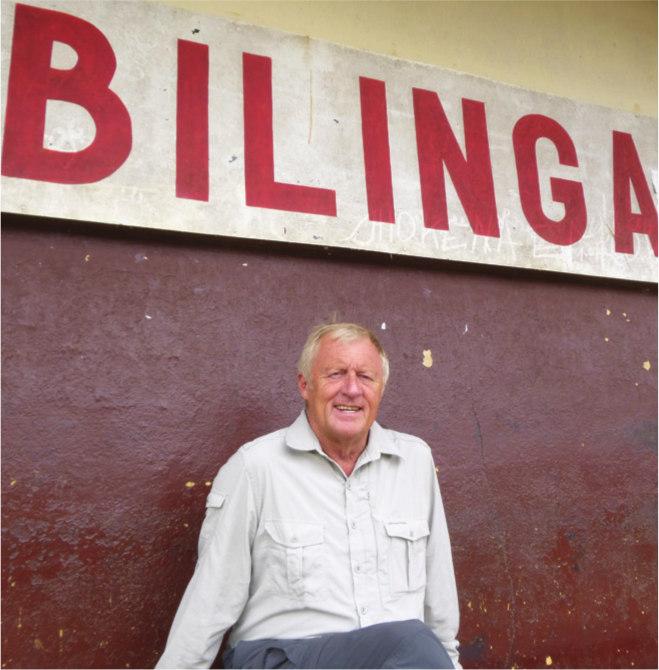

Before I learned that it was near Bilinga station that a crash claimed the lives of many passengers.