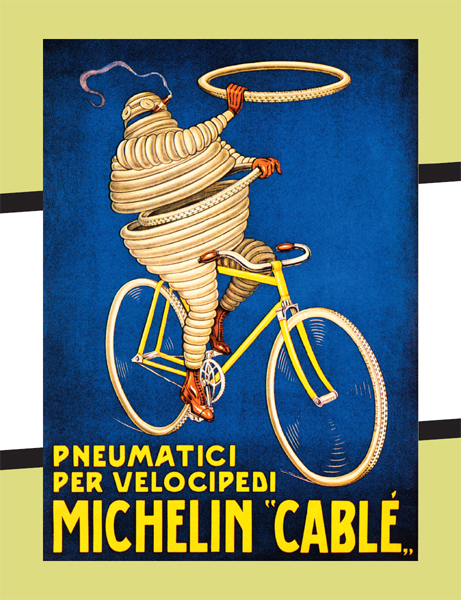

A 1920 poster of the Michelin Man, who is actually called Bibendum.

THE JOY OF CYCLING

There are a number of moments that serve as waypoints in everyones life. Your first childhood memory, your first day at school, a kiss, a wedding, the birth of a child. But among these memories one remains indelible the day you first learned to ride a bike.

It is a wonderful moment when balance materialises, fear disappears and you are transported, almost magically, through space and time. It is a moment of growing up when you put away your childish stabilisers. But it is also the moment when a second childhood begins. Everyone feels younger, happier and freer on a bicycle. Compared to the drudgery of walking, or the complications of a car, bikes offer a form of simple everyday enchantment. Who would think that some metal, some rubber and a chain could offer such a wonderful return on an investment, where pedalling is not a chore but a joy.

And whereas some inventions have fallen by the wayside the steam train, perhaps soon the internal combustion engine the bicycle keeps going strong. And stronger. Whereas car and bicycle production were neck and neck until about 1965, with 20 million of each being produced each year, since then bikes have broken from the pack. Since 2003 more than 100 million bikes are produced each year, more than twice the amount of cars. Moreover, bicycles never die. Whereas cars soon become obsolete, and crushed to make way for newer models, bikes are daily being restored by enthusiasts. Their punctures are fixed, their chains lubricated, their handlebars shone: reborn and returned to their former glory, and capable of keeping up with the best of them.

Despite their simplicity, the world of bikes is as wonderful and wide-ranging as life itself. So welcome to The Splendid Book of the Bicycle. Here you will learn not only about bikes, but their history, their achievements and what they might one day become. You will explore bicycles in wartime, bicycle aerodynamics, bikes in the movies and the greatest bicycle adventurers of all time. The Splendid Book of the Bicycle is a companion to mankinds greatest companion (apart from his dog) his bike.

A classic: the folding BSA paratrooper bike from the Second World War.

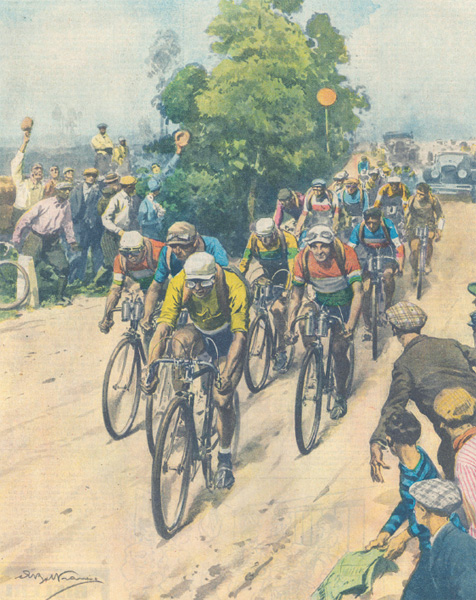

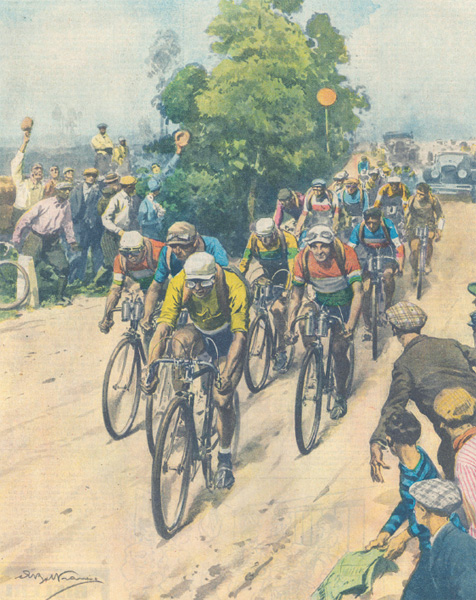

An illustration from the Italian Newspaper La Domenica del Corriere from 1930: a group of Italian riders from that years Tour de France.

CONTENTS

Wipeout! During a 100 km race at New York in 1923, a nasty pile-up occurs on the first bend.

HOBBY HORSE TO BONESHAKER

When and where the bicycle was first dreamt of is shrouded in the mists of time. The wheel was invented in antiquity, and before that the roller a smoothed tree trunk had transported stones to the pyramids and Stonehenge. Carriage and cart technology had improved over the centuries, to the extent that by the mid-1700s passengers enjoyed large, spoked carriage wheels, with steel axle inserts and flat steel tyres. But the drive for improvement that characterised the late eighteenth-century Enlightenment would not stop there. There was an innate faith in the power of reason, and the power of a mechanical world-view. Surely mankind could do better than simply to continue his age-old reliance on the horse?

And it was this belief in the power of human invention that led the German Karl Drais to invent, in 1817, the Laufmaschine (running machine). Drais was a German aristocrat with radical sympathies, who was to go on to support the Revolution of 1848. He was also a prolific inventor, inventing a typewriter, a music recording machine and a meat grinder. But it is his pioneering Hobby Horse that has become his most lasting legacy.

Draiss innovation was to relinquish the obsession with two- or three-wheeled machines that were driven by hand-cranks, all of which were underpowered and difficult to steer. Drais realised that a two-wheeled machine could be balanced by small modifications in steering, and steered using greater deviations. In effect Drais provided a form of heightened walking, or running, with the strong muscles of the legs providing power, but the wheels providing a boost to forward motion. As with all great inventions it was simple, but powerful as can be seen in the way the design lives on in modern balance bikes designed for toddlers.

And as with all great inventions it was soon imitated. The following year Denis Johnson of London had copied but improved on Draiss original, adding footrests and smoother lines. And soon in both France and England, Draiss invention had become all the rage among young fashionable aristocrats, becoming known as the Draisienne or velocipede (fast feet) in France, and the Hobby Horse or Dandy Horse (because unlike a real horse it did not require constant maintenance) in England. Cartoons soon ridiculed this new aristocratic fad. One cartoon entitled Anti Dandy Infantry triumphant or the Velocipede Cavalry Unhobbeyd, showed a blacksmith, fearful for his job, smashing up one of the offending vehicles, and a vet, fearful for his employment too, administering a large lethal syringe to the crashed rider. In the background a dog chases another hobby-horser into the distance. Despite its unpopularity among members of the non-riding public, the bicycle (of sorts) had arrived.

The Boneshaker, the next stage in the bicycles evolution, was a natural progression from the Hobby Horse. In fact, the story goes that in 1861 the Parisian blacksmith Pierre Micheaux was repairing a Hobby Horse in his workshop when he decided to fit pedals and cranks to the front wheel. (Other accounts stress the role of Pierre Lallement, a baby carriage manufacturer from Nancy, who filed a patent for a similar design in 1866.)

Micheauxs design came to be called a boneshaker because unlike the Hobby Horse, all the riders weight was placed on the saddle, rather than also being conveyed to the ground via the legs. It was in some ways unstable as the power applied to the pedal had a tendency to twist the front wheel to one side. The ride was a rough one, with wooden wheels and iron tyres rattling along the cobbled streets of nineteenth-century France. But there were some concessions to comfort via a sprung seat, lubricated brass bearings and safety, in the form of a rudimentary brake: a wooden pad pressed against the rear wheel. A print from 1869 shows a Boneshaker outpacing a horse, with the caption: We can beat the swiftest steed, With our new velocipede.

Micheauxs Bicycle Company was formed in 1868, producing bicycles at the rate of five a day, and the design soon caught on. Other manufacturers carried out their own innovations. The Scotsman Thomas McCall powered the rear wheels by a system of cranks linked to the pedals, trying to obviate the need for the Boneshaker rider to sit almost astride the front wheel. Other manufacturers introduced metal rather than wooden spokes, and shod their bikes with solid rubber wheels. By 1869, Boneshakers were being produced in their thousands. The bicycle proper had been born, converting the up-and-down motion of walking into the cyclical motion of the wheel.

Next page