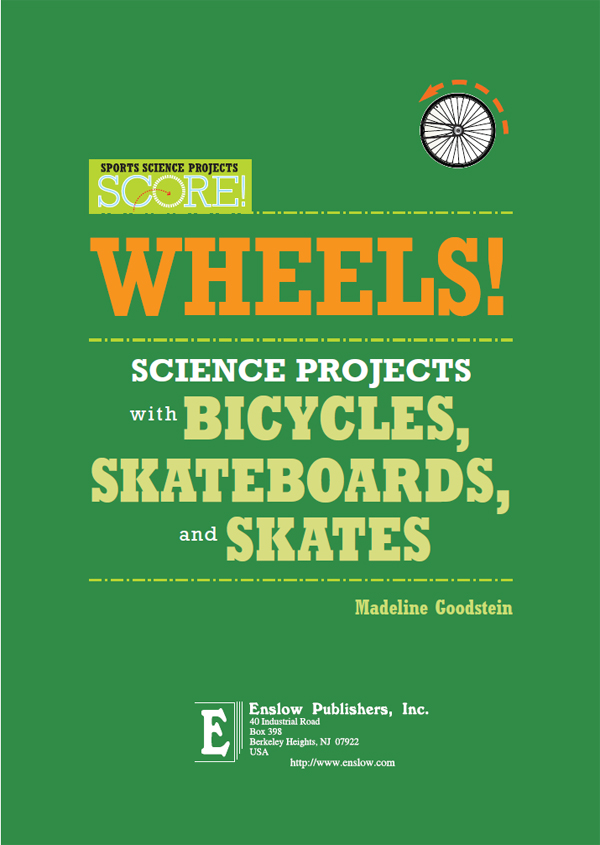

Science On Wheels

How do bicycle gears work? How do you do an ollie on a skateboard? What's the best way to get up after falling on your skates?

There is lots of physics involved in wheeled sports like bicycling, skateboarding, and roller skating. Have fun learning about gravity, friction, the laws of motion, and more while enjoying a favorite sport. Great ideas for science fair projects follow many experiments.

"Fun experimental methods, like riding bikes through puddles and turning on a skateboard, will engage all students who love wheeled sports."

Jim Valles, PhD, Series Science Consultant

Professor of Physics

Brown University, Providence, RI

About the Author

Madeline Goodstein, PhD, is a retired professor of chemistry from Central Connecticut State University. She is the author of numerous science project books, including Sports Science Projects: The Physics of Balls in Motion with Enslow Publishers, Inc.

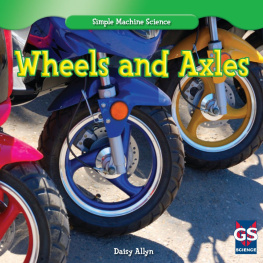

CAN YOU IMAGINE WHAT THE WORLD WOULD BE like today if wheels had never been invented? There would be no automobiles, no trains, no watches, no electric motors, no disk drives, no electric generators, no CDs or DVDs, no washing machines, no pulleys, no Ferris wheels, no wagons, and no motorcycles. There would be no roller or in-line skates, no skateboards, and no bicycles. And that is only a small part of the list. The wheel is probably the most important mechanical invention ever.

Why is the wheel so effective? How can its motion and that of objects on wheels be explained? The laws of physics can tell us. Physics is the science that deals with motion. This book will introduce you to those laws of physics that explain the motions of three very popular sports on wheels. The three are bicycling, skateboarding, and roller skating. These three sports are united because they all use wheels. They are also united by the fact that the wheels all depend on human muscle power. No motor turns the wheels and no animals carry or help push or pull the riders.

Thanks to the wheels, the riders in all three sports are able to travel long distances using their own muscle power. They can glide along silently while enjoying the views around them. Moreover, the riders can make breathtaking turns on skates, launch themselves from skateboards high into the air, and race up a mountainous road on a bicycle.

Each of the chapters in this book contain experiments for you to do. The experiments are easy to carry out, use materials readily available, and help to clarify the laws of physics. Most experiments also include ideas for projects that you might do for a science fair.

Although wheels have been part of European and Asian civilizations for many centuries, the sports of roller skating, skateboarding, and bicycling appeared much more recently. Perhaps the earliest was the skeeter, which appeared in Holland in the early 1700s. Ice skating in Holland was used to travel the numerous frozen waterways but was limited to the icy season. Some clever person invented dry-land skating for the summer by using wooden spools. He nailed the spools to strips of wood and attached them to his shoes. However, skeeters never got much use because of the muddy grounds and rough road surfaces in the summers.

Roller skating appeared next, followed by bicycling, as will be discussed later. The skateboard is the youngest of the three, having been around for a mere one hundred years.

Any use of wheels for sports can injure the rider if proper safety precautions are not taken. When engaged in experiments using a wheeled device, always wear the protective helmets developed for each. Also wear wrist protectors and knee and elbow pads for skateboards and skating. When carrying out experiments where you ride on wheels, make sure a skilled adult is always present. Obtain the approval of a responsible adult before carrying out any of the science project ideas. When you need to carry out an experiment on a sidewalk, avoid busy streets. For any experiment on a road, pick one where there is very little or no traffic and have someone present to warn you if a car is coming. Never do any of the wheeled sports when feeling tired, faint, or even slightly dizzy.

In carrying out the many experiments that are in this book, you will usually have an idea of what you expect to happen. That expectation, based upon your previous experience, is called a hypothesis. After you have completed the experiment, you will be able to conclude whether or not the hypothesis was supported by the evidence that you gathered. That is the nature of scienceto develop hypotheses and to gather evidence showing whether or not a hypothesis is true. If, eventually, there is considerable evidence in favor of the hypothesis and none that contradicts it, the hypothesis is elevated to the level of a theory. The theory will probably suggest more hypotheses, which will require more experiments and so on and on, producing more and more scientific knowledge.

Scientists are always careful to keep dated records of their experiments. The records include information on what they did, the observations made, and the conclusion reached. As you carry out the experiments in this book, be sure to do the same.

With the help of this book, you can investigate what laws of nature make the use of a wheel so advantageous, why the use of wheels makes moving along much easier than just walking, how you can balance so as not to fall off the wheeled device, and many other aspects of the sports. Each of the three self-propelled wheeled sports will be examined in a separate chapter. The three sports are popular because they are such fun. Although each sport is very different from the others, they are united by the laws of physics and by the wheels on which they move. A chapter on wheels starts the book.

WHAT IS A WHEEL? A WHEEL IS A CIRCULAR device capable of rotating on a real axis. And what is an axis? An axis is a straight line, real or imaginary, passing through a body that rotates around the line. We all know that the earth rotates around a line through its center. That line is imaginary, not real. A wheel, however, always rotates around a real axis, such as a round rod that passes through its middle from one side to the other.

The date of the appearance of the first operating wheel is shrouded in the mystery of the early times of human existence. The oldest single wheel found so far is a potters wheel discovered in the region between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers (now Iraq). It dates back to about 3300 b.c. Wheeled vehicles may have quickly followed the discovery of the wheel. A wheel with spokes was first used for chariots in Egypt in about 2000 b.c.

There has never been a visible wheel in the biological structure of a plant or animal on this planet. Although bacterial flagella, dung beetles, and tumbleweeds all use rotation for moving along, none has a real axis of rotation.

The Romans produced a remarkable variety of wheeled vehicles. They built light, speedy chariots drawn by horses that were used for hunting animals, for sport, and for warfare. They also made farm carts with two wheels, four-wheeled wagons for heavy freight, and coaches for transportation of people. They built a network of roads for foot and wheeled travel that helped to unite the empire. Some of these roads are still used today.