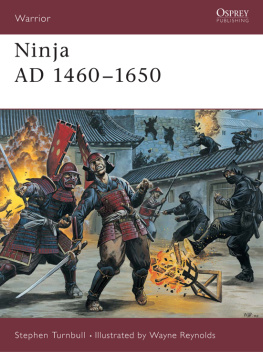

Warrior 64

Ninja

AD 14601650

Stephen Turnbull Illustrated by Wayne Reynolds

CONTENTS

NINJA AD 14601650

INTRODUCTION: THE ELUSIVE NINJA

F ew military organisations in world history are so familiar yet so misunderstood as Japans ninja, so to write a Warriors book on the topic provides a unique challenge. Ninja certainly existed, but so much myth and exaggeration has grown up around the undoubted historical core of the subject that writing a book such as this could be almost as daunting a prospect as producing a Warriors volume on the outlaws of Robin Hood. To resolve the matter I have decided to play it straight. Any references to ninja that could fly will be identified as the myths they are. Quotations from written accounts of ninja exploits will be confined to chronicles that are respected for their accuracy. Descriptions of items of ninja equipment will be confined to implements illustrated in old ninja manuals such as the 17th-century Bansen Shukai, or preserved in one of Japans several (and remarkably underplayed) ninja museums. The reader will therefore find collapsible ladders, secret explosives and hidden staircases, but will have to look elsewhere for human cannonballs and ninja submarines.

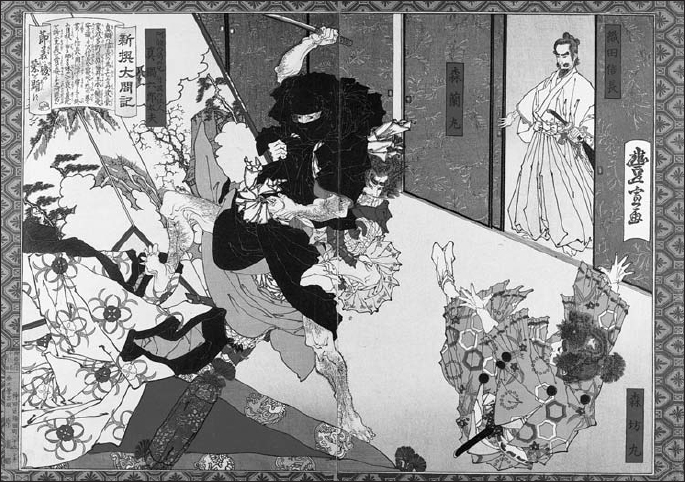

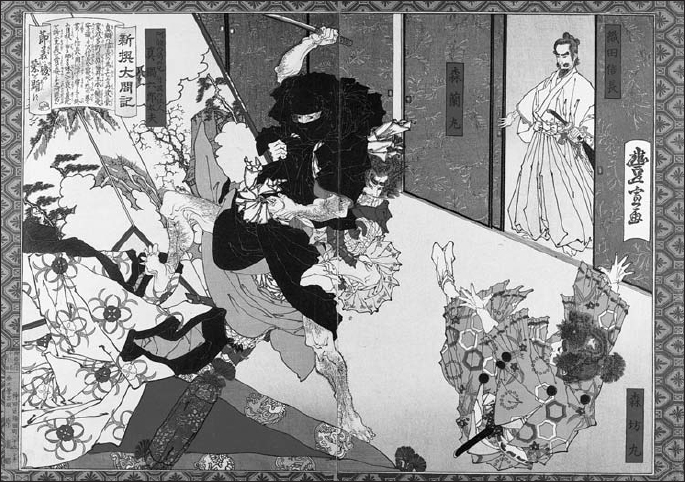

This woodblock print by Yoshitoshi is a fine print of a ninja assassination. The traditional details associated with ninja are perfectly depicted. The ninja is attempting to murder Oda Nobunaga in 1573. He tried to sneak into Nobunagas castle of Azuchi to stab Nobunaga while he was asleep in his bedroom, but was discovered and captured by two of the guards. He then committed suicide, and his body was displayed in the local market place to discourage any other would-be killers.

NINJA JAPANS SECRET WARRIORS

For any military historian the ninja remains one of the most fascinating mysteries of Japanese samurai warfare. The word ninja or its alternative reading shinobi crops up again and again in historical accounts in the context of secret intelligence gathering or assassinations carried out by martial-arts experts. Many opportune deaths may possibly be credited to ninja activities, but as they were so secret it is impossible to prove either way. The ways of the ninja were therefore an unavoidable part of samurai warfare, and no samurai could ignore the secret threat they posed, which could ruin all his carefully laid plans. As a result ninja were both used and feared, although they were almost invariably despised because of the contrast their ways presented to the samurai code of behaviour. This may be partly due to the fact that many ninja had their origins in the lower social classes, and that their secretive and underhand methods were the exact opposite of the ideals of the noble samurai facing squarely on to his enemy.

This paradox, that ninja were beneath contempt and yet indispensable, is a theme running through the whole history of ninja warfare. It is also fascinating to note that the popular extension of the image of the ninja to a superhuman that could fly and perform magic also has a surprisingly long history in Japan. Such stories were being told as early as the beginning of the 17th century, when many of the historical accounts became mixed up with other legends.

The roots of the ninja

Secret operations, from guerrilla warfare to the murder of prominent rivals, are topics that may be found throughout Japanese history, but it is only from about the mid-15th century onwards that we find references to such activities being carried out by specially trained individuals who belonged to organisations dedicated to this type of warfare. Much of the activity is focused around the Iga and Koga areas of central Japan, so this location and time period will provide the major setting for this book.

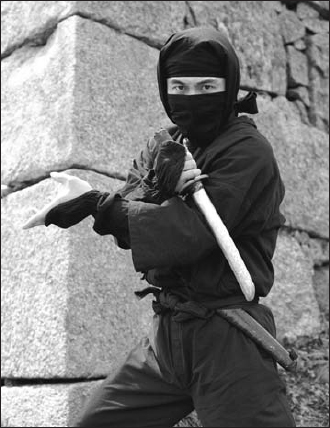

Ninja with sword. A member of the Iga-Ueno ninja re-enactment society poses for the camera during the 2002 Ninja Festival.

The traditional view of the ninja as a secret, superlative, black-coated spy and assassin derives from two different roots. The first is the area of undercover work, of espionage and intelligence gathering (and even assassination) that is indispensable to the waging of war. The second is the use of mercenaries, whereby the leaders of military operations pay outsiders to fight for them. In Japan these two elements came together to produce the ninja and, curiously enough, the ninja provide almost the only example of mercenaries being used in Japanese warfare. Part of the reason for this was that secret operations were the antithesis of the samurai ideal. A daimyo (warlord) would not wish to have his brave and noble samurais reputations soiled by carrying out such despicable acts. Instead he paid others to do them. It was an unusual but highly valued service, and the Japanese historian Watatani sums up the situation as follows:

So-called ninjutsu techniques, in short are the skills of shinobi-no-jutsu and shinobi-jutsu, which have the aims of ensuring that ones opponent does not know of ones existence, and for which there was special training. During the Sengoku Period such techniques were used on campaign, and included sekko (spy) and kancho (espionage) techniques and skills.

The term shinobi is merely the alternative reading of the character nin; hence shinobi no mono rather than ninja. But ninja trips more readily off a Western tongue, and has therefore become the popular term.

The ancestors of the ninja

As undercover operations are fundamental to the conduct of war in any culture, it is not surprising to read of such techniques being used throughout Japans own turbulent history, but the first written account confirms that even at that early stage such activities were somehow questionable, even when they produced results. In Shomonki, the gunkimono (war tale) that deals with the life of Taira Masakado and was probably completed shortly after his death in AD940, we read:

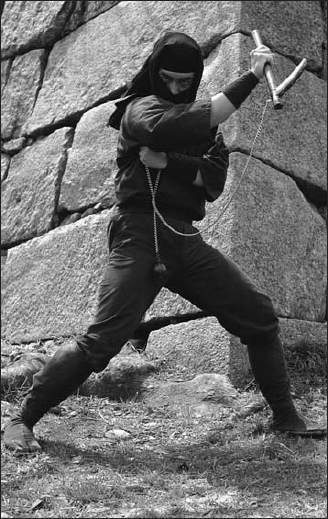

Ninja with a shinobi-gama (kusari-gama). Combination weapons involving sickles were a popular choice for ninja.

Over forty of the enemy were killed on that day, and only a handful managed to escape with their lives. Those who were able to survive the fighting fled in all directions, blessed by Heavens good fortune. As for Yoshikanes spy Koharumaru, Heaven soon visited its punishment upon him; his misdeeds were found out, and he was captured and killed.

Spying was the classic ninja role, so we may note here the first written confirmation that such activities were perceived as contrary to samurai behaviour. Like Shomonki, the two greatest gunkimono, Hogen Monogatari and Heike Monogatari, were written for an aristocratic audience who wished to hear of the glorious deeds of their ancestors. The activities of the common foot soldiers, who outnumbered the mounted samurai by 20 to one in the armies of the time, are almost totally ignored, so it is not surprising that stories of ignoble undercover acts are conspicuous by their absence. The one exception is the story that begins