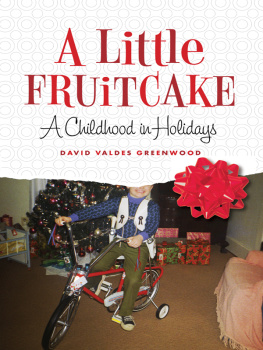

A Little Fruitcake

Copyright 2007 by David Valdes Greenwood

Definition on page ix 2006 by Houghton Mifflin Company.

Reproduced by permission from The American Heritage Dictionaryof the English Language, Fourth Edition.

Some of the elements of the chapter Ambrosia appeared in different form in the pages of the Boston Phoenix.

One name has been changed for the comfort of someone I love, at her suggestion.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Printed in the United States of America.

Designed by Timm Bryson

Set in 10.75 point New Baskerville by The Perseus Books Group

Cataloging-in-Publication data for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

First Da Capo Press edition 2007

ISBN-10: 0-7382-1122-2

ISBN-13: 978-0-7382-1122-0

Published by Da Capo Press

A Member of the Perseus Books Group

http://www.dacapopress.com

Da Capo Press books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the U.S. by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA, 19103, or call (800) 255-1514 or e-mail .

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

For my brother, Ignacio,who endured me

fruitcake (froot

kak) n. 1. A heavy, spiced cake containing nuts and candied or dried fruits. 2. Slang. A crazy or an eccentric person: a fruitcake underthe delusion that he was SaintNicholas. ( John Strahinich)

kak) n. 1. A heavy, spiced cake containing nuts and candied or dried fruits. 2. Slang. A crazy or an eccentric person: a fruitcake underthe delusion that he was SaintNicholas. ( John Strahinich)

from The American Heritage Dictionary,Fourth Edition

1

The Powder Keg Under the Tree

As I held the foil-wrapped shoebox in my hands, I could hardly breathe. I was five years old, possessed by a question of life-or-death importance: would my present cry or wouldnt it?

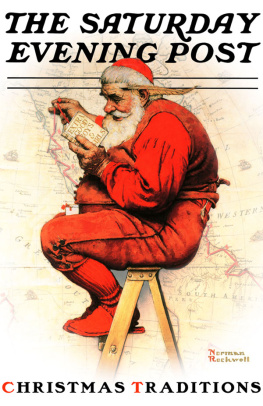

The package in my hands was the culmination of my lifes work, or so it seemed in 1972. I had put in my request in Novembernot of that year, mind you, but a month before the previous Christmas. The fact that my request had already gone unfulfilled for one holiday is telling. Even at five, I knew that if the box in my hands contained what I dreamed of, then I had accomplished a feat even grander than talking my grandmother into letting me stay up late to watch A Charlie Brown Christmas.

November 1971 marked the first holiday season since my mother had left my Cuban migr father in Miami and returned home to rural Maine, where shed been raised. After apartment life in Boston and then the Little Havana section of Miami, we found ourselves living in a real house like nothing my brother, Ignacio, and I had seen before.

Over two hundred years old, my grandparents house was constructed in New England farmhouse colonial style: a shed attached to a building that housed the porch and kitchen, which was then attached to a two-story structure housing the bedrooms, dining room, and living room. It looked like many of the houses in Norridgewock, Maine, which is to say, like a fat white caterpillar whose segments were punctuated with doors and windows. There was an earthen cellar below, where Grammy kept all her canning, and a newspaper-lined attic over the shed that we used as a garage. We had two deep wells for water and an enormous garden outlining the backyard in an L-shape. About the only thing reminiscent of Miami was the clothesline strung from the shed to an ancient maple, the shirts and sheets flapping in the wind just as they had on the lines in Little Havana.

When Mom moved back into her parents home with my older brother and me, she was forcibly returning Grammy and Grampyboth shoe shop workers on the brink of retirementto a life they were sure they had left behind: child raising. But they managed to adapt with equanimity, turning the spare room into a bedroom for two boys and setting an elderly swing set on the once-unspoiled front lawn.

One of my earliest memories at Grammys house is of that first Thanksgiving. All the grown-ups had gathered in the living room late in the afternoon, and Uncle Howard asked me what I wanted for Christmas. Uncle Howard was one of many not-really-related-to-us aunts and uncles in our lives. On Thanksgiving, with the few adult-sized chairs taken, he sat on an ottoman made by Sister Lee from church. This nifty footstool was really just three metal milk cans covered in colorful fabric and dressed up with pom-pom fringe, a very low post that put him much closer to my height than the other adults. I could look him in the eye as I answered eagerly: I wanted a baby doll.

Who knows where that came from? My playmates were all other boys. I cant picture taking anyone elses baby doll for a spin only to decide I needed one of my own. Maybe I saw a newborn baby somewhere, and thought, Surely there must be a plastic version out there for little boys like me.

Its a better bet that I saw a doll while watching television. Despite being devoutly religious, our family nonetheless watched a lot of television. The afternoons were a smorgasbord of what Grammy called my stories. It is odd that soaps were so beloved by a woman who objected to her grandsons seeing Batman reruns (too violent) and, a few years later, WonderWoman (outfits too skimpy). Day in and day out, once Grammy finished her chores, she and Mom took up their stations in the living room, juggling Days of OurLives, All My Children, One Life to Live, Edge of Night,Search for Tomorrow, and General Hospital, a feat that required missing half an hour of one soap to catch the last half-hour of another. Perhaps sandwiched between the antics of evil Phoebe Cane or nice Nurse Jesse, I saw an ad for a baby doll.

All I know is that my desire was clear and my answer so primed that it burst out without hesitation, silencing a roomful of grown-ups who had been enjoying the tryptophan stupor of their Thanksgiving feast. Did they laugh? Did they ask me if they had heard correctly? I remember a hiccup of silence and a vague awareness of some disapprovalnot surprising since every person in that room went to our church. We were fundamentalists who (despite our obsession with television) eschewed a host of sinful activities from drinking to dancing to playing cards. The tenets of our faith most certainly did not include encouraging boys to play with dolls, but if anyone said so that afternoon, I dont recall it. My clearest impression is of having made my request.

As far as I knew, it was a done deal. I didnt doubt for a second that I would get a doll that Christmas because, from the moment my brother and I had come home to Maine from Miami, relatives and friends had fawned over us as if we had just splashed down safely after a mission to the moon. In my innocence, I believed that only a matter of weeks stood between me and the baby doll of my dreams.

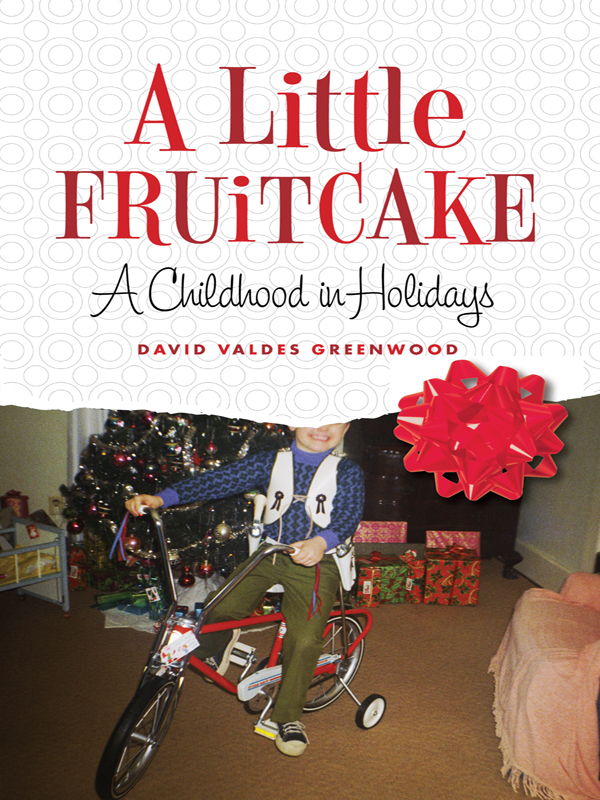

I was mistaken in this regard. My brother and I each got the exact same five gifts: a blow-up octopus, the powdery smell of which still lingers in my memory; a metal train; a plastic snowmobile; a helicopter; and a mechanical dog that barked. In a photo of that Christmas, Ignacio and I sit on my bed, side by side, with our matching bowl cuts and new toys gathered around us. There is no doll.

kak) n. 1. A heavy, spiced cake containing nuts and candied or dried fruits. 2. Slang. A crazy or an eccentric person: a fruitcake underthe delusion that he was SaintNicholas. ( John Strahinich)

kak) n. 1. A heavy, spiced cake containing nuts and candied or dried fruits. 2. Slang. A crazy or an eccentric person: a fruitcake underthe delusion that he was SaintNicholas. ( John Strahinich)