Contents

Guide

HOW TO USE THIS EBOOK

Select one of the chapters from the and you will be taken straight to that chapter.

Look out for linked text (which is in blue) throughout the ebook that you can select to help you navigate between related sections.

You can double tap images and tables to increase their size. To return to the original view, just tap the cross in the top left-hand corner of the screen.

INTRODUCTION

n 1983 a researcher named David Wade Chambers developed the Draw-a-Scientist Test. It was a simple way to work out when children began developing an image of the typical scientist in their heads. Did they see them as bespectacled geniuses in lab coats? Wild-eyed sorcerers with frizzy hair and potions? Or shy bookworms with their nose buried in a pile of academic papers?

n 1983 a researcher named David Wade Chambers developed the Draw-a-Scientist Test. It was a simple way to work out when children began developing an image of the typical scientist in their heads. Did they see them as bespectacled geniuses in lab coats? Wild-eyed sorcerers with frizzy hair and potions? Or shy bookworms with their nose buried in a pile of academic papers?

Over the next 11 years, Chambers administered tests to more than 4,000 children between the ages of 5 and 11. The results were singularly depressing: of the thousands of drawings produced, only 28 featured female scientists. These were all drawn by girls, who made up 49 per cent of the study; there wasnt a single picture of a woman drawn by a boy. In other words, in the eyes of an average child, a scientist was far likelier to be a bearded figure shouting something like Eureka! and Ive got it! than a female.

This isnt a slight on the schoolchildren of Montreal, Quebec, where the majority of the studys subjects came from. But if children are supposed to be our future, then the future at least when it comes to science is looking very male indeed.

According to the Women in Science and Engineering (WISE) campaign, women currently occupy just 21.1 per cent of the total STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) jobs in the UK.

These elite schools and academies were and still are seen as the gatekeepers of scientific accomplishment: training ground, career-making research centre and intellectual hothouse all in one. And in the past they were about as open-minded as an 11-year-old Montreal schoolchild when it came to who could pass through their doors.

So does this mean that the history books are totally empty of women making earth-shattering discoveries, teasing out scientific truths or publishing bombshell revelations about the inner workings of the universe? Of course not.

Cant get into university? No problem. In the 18th century, French mathematician dressed up in male drag so that she could stroll into Caf Gradot to discuss equations.

If you look even further back, you can find women in antiquity and medieval times who were scientific trailblazers in their own right, and whose contributions to their field are still alive and well. (also known as Maria the Prophetess), was so highly regarded as a chemist and alchemist in the ancient world that she was rumoured to have discovered the Philosophers Stone itself, but the innovation for which she is best known is the bain-marie, or the double boiler, which is still used in kitchens today.

Even longer ago, was pioneering gynaecological and surgical techniques that any doctor will find familiar today, including a way to rotate a breech baby for birth.

But if you had asked me to draw a picture of a scientist as a child, I wouldnt have drawn any of these women. In all honesty, I would probably have drawn a picture of a man. You see, even though I had been taught by female science teachers and went to an all-girls elementary school, I had still absorbed and digested the stereotype of what a scientist should look like. By the age of 14, you were most likely to spot me in a chemistry or mathematics class, throwing my hands up in the air and saying, I just cant do it, and my teachers affirming, Well, that is the one thing you definitely got right.

Shamefully, I still carry the remnants of that attitude with me now. If I offer to split a bill at a restaurant, Im scared that even working it out on my phone, let alone in my head, would show me up as mathematically incapable. Yet every time Ive had to do it, Ive surprised myself with how capable I can be.

I suspect thats true for a lot of girls in science classes. Girls and boys are not born able to wield a Bunsen burner or a calculator with any more or less competence than the other, but adults tend to have lower expectations of the girls abilities. The girls then internalize these lessons over time, becoming a little less confident and a little less outspoken with every passing comment, until the words come tumbling out of their own mouths: Dont ask me! I cant do it!

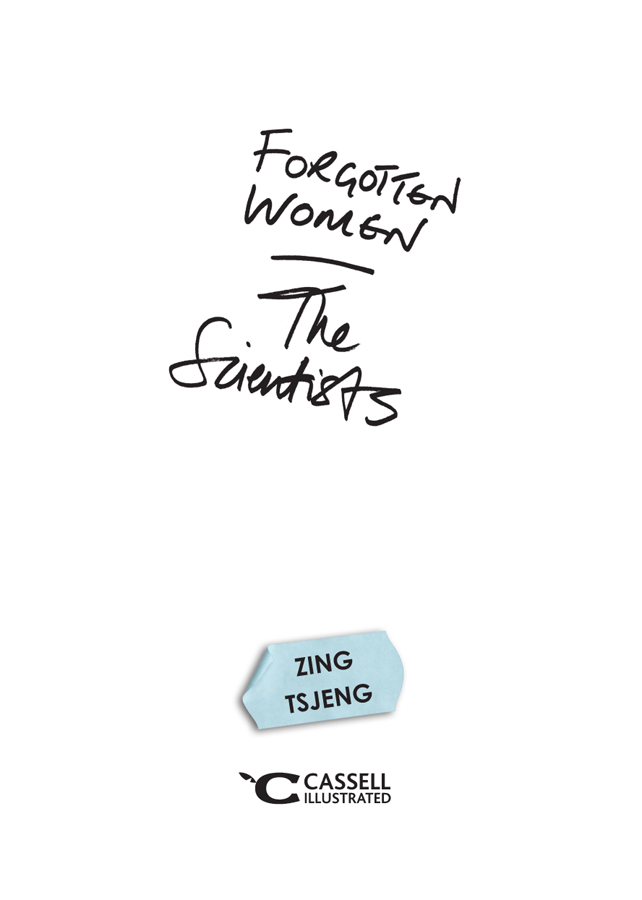

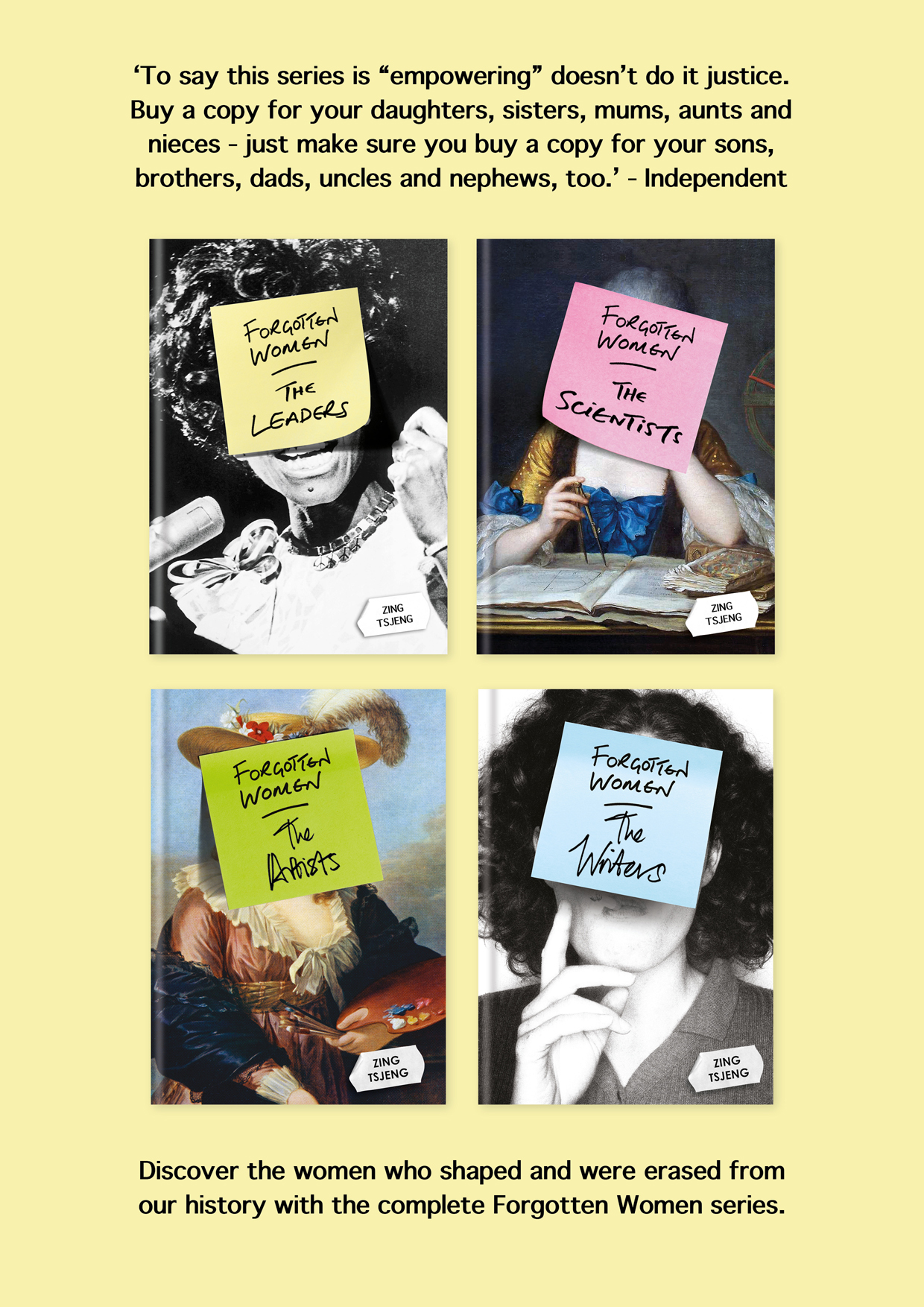

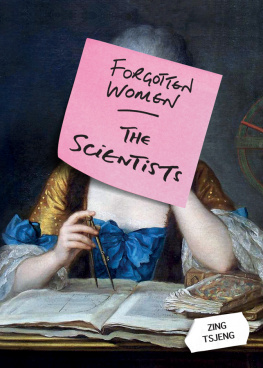

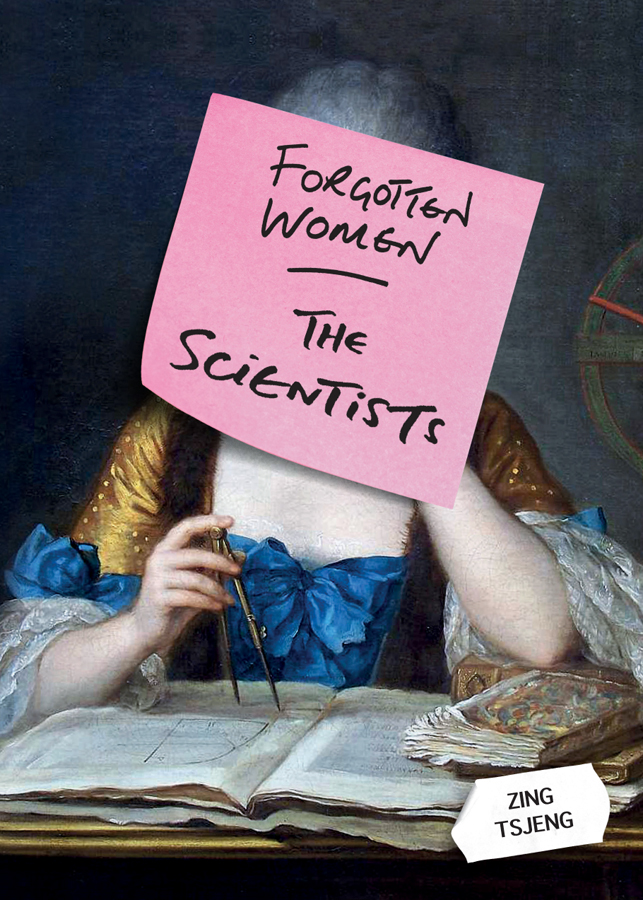

Forgotten Women: The Scientists has been a way of re-educating myself and to show that there were plenty of women who couldnt just do it: they did it exceedingly well, and better than anybody else, often while confronting incredible levels of sexism and at exceedingly high personal cost.

History is full of brilliant women who were forced to accept unpaid jobs as volunteers or assistants just to get their foot in the lab door. Or who were made to resign or step down from their positions after getting married (the logic presumably being that they were better suited to wearing aprons than they were lab coats and goggles).

And when these women made an incredible discovery of their own the kind that cracks open the field of nuclear fission, for instance they were often conned out of their rightful acknowledgment. The praise was redirected to male collaborators, research partners and in more than one case husbands.

Its little wonder that when British astronomer Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin looked back on her decades-long career in science, she didnt mince her words: A woman knows the frustration of belonging to a minority group. We may not actually be a minority, but we are certainly disadvantaged.

Working with The New Historia at the New School, Parsons, we picked 48 women to profile for each book in the Forgotten Women series: 48, because thats the total number of women who have won the Nobel Prize between its inception in 1901 and 2017, when its latest batch of winners was announced at the time of writing. Thats 48 out of 911 Nobel Laureates in total, going back all the way to the beginning of the 20th century. Some of those womens stories are detailed here. Others, like DNA crystallographer , were arguably cheated out of their Nobel.

Trawling through the length and breadth of scientific history to choose the women in The Scientists was a daunting and humbling task. I have attempted to include a truly diverse and representative mix of scientists from all over the world. However, theres no getting away from the fact that science is just as bad on ethnic diversity as it is on gender equality. Privileged women in the West were often the first to benefit from new scientific opportunities: you just need to look at to see an example of where black women were employed at the US space agency only after their white counterparts were admitted.

n 1983 a researcher named David Wade Chambers developed the Draw-a-Scientist Test. It was a simple way to work out when children began developing an image of the typical scientist in their heads. Did they see them as bespectacled geniuses in lab coats? Wild-eyed sorcerers with frizzy hair and potions? Or shy bookworms with their nose buried in a pile of academic papers?

n 1983 a researcher named David Wade Chambers developed the Draw-a-Scientist Test. It was a simple way to work out when children began developing an image of the typical scientist in their heads. Did they see them as bespectacled geniuses in lab coats? Wild-eyed sorcerers with frizzy hair and potions? Or shy bookworms with their nose buried in a pile of academic papers?