Contents

Guide

CARLOTA LUCUM

n the 19th century, Cuba was every bit the booming, prosperous Spanish colony. But its wealth had a dark side it flourished off the backs of thousands of slaves who worked on its plantations and in its sugar mills. By 1841, for the first time in Cubas history, a population census revealed that there were more slaves than white residents. Out of one million people, there were 436,000 slaves, 153,000 free people of colour and just 418,000 whites. The implications of the census were keenly felt among the Spanish authorities, who began to sense that the days of their grip on power demographically, at least were numbered.

n the 19th century, Cuba was every bit the booming, prosperous Spanish colony. But its wealth had a dark side it flourished off the backs of thousands of slaves who worked on its plantations and in its sugar mills. By 1841, for the first time in Cubas history, a population census revealed that there were more slaves than white residents. Out of one million people, there were 436,000 slaves, 153,000 free people of colour and just 418,000 whites. The implications of the census were keenly felt among the Spanish authorities, who began to sense that the days of their grip on power demographically, at least were numbered.

In 1843 this division was brought into stark relief. Black slaves, as well as free people of colour and even some white Cubans, began to sorely resent Spanish rule over the island which was especially galling when Cuba did not even have political representation in Madrid. In November, what became known as Cubas largest countryside uprising took place, thanks to an African slave called Carlota Lucum (unknown1844)

Not much is known about Carlota; as with many slaves, her true identity was stripped from her as she made the transatlantic crossing to the New World. But her last name may give some indication of her past: Lucum was the name given to Cuban slaves who spoke the Yoruba language of West Africa. Yoruba women, from what is now Nigeria, are known to have led troops into battle; some historians believe that Carlota may have been of noble birth and therefore familiar with matters of military planning. This helps explain her fearlessness and skill at moulding her ragtag group of rebel slaves into a fearsome army.

Rebellion had been brewing on the island since March that year. Near the port city of Crdenas, some 116km (72 miles) east of Havana, slaves at a sugar mill killed three workers and razed buildings to the ground. Travelling along the railway tracks to neighbouring plantations, they recruited other slaves and workers to their cause. In response, the Spanish government sent soldiers and bloodhounds after them. Many were shot or hanged but the sudden outburst of violence and the subsequent repression lit a fuse across the surrounding countryside of Matanzas province. That summer, the air was filled with the pounding sound of slaves playing the traditional talking drums, urging others to join them in revolt.

Carlota was one slave who answered the call. Fermina, an enslaved woman from the nearby Acana sugar estate, had been imprisoned two months earlier for plotting rebellion. Carlota joined a group of other slaves to free Fermina, and she led an uprising at both the Acana mill and another plantation, the Triunvirato sugar estate. The slaves killed their overseers, took their weapons and set buildings ablaze. Ruthless and vengeful, Carlota took no prisoners. Later, one of her targets the Triunvirato overseers daughter spoke of her terror during the attack, saying that Carlota wounded her with a pruning machete and only fell back when her male companions told her that her victim was probably already dead. In March 1944, at some point during the uprising, Carlota was struck down; her body was found the following morning.

The Spanish colonial authorities were vicious in their crackdown. In the wake of the uprising, thousands of black people around Matanzas slaves and free people of colour alike were taken into custody. Many were lashed and tortured to death without trial; one American visitor, Dr John Wurdemann, described slaughterhouses, in which a thousand lashes would be inflicted on a single victim to extort confessions.

But Carlota had the last laugh. Less than half a century later, slavery was finally abolished in Cuba, and she emerged as a Cuban symbol of freedom and resistance against colonial oppression. Today, in the grounds of the ruined Triunvirato mill, there stands a statue of Carlota, holding a machete in her hand.

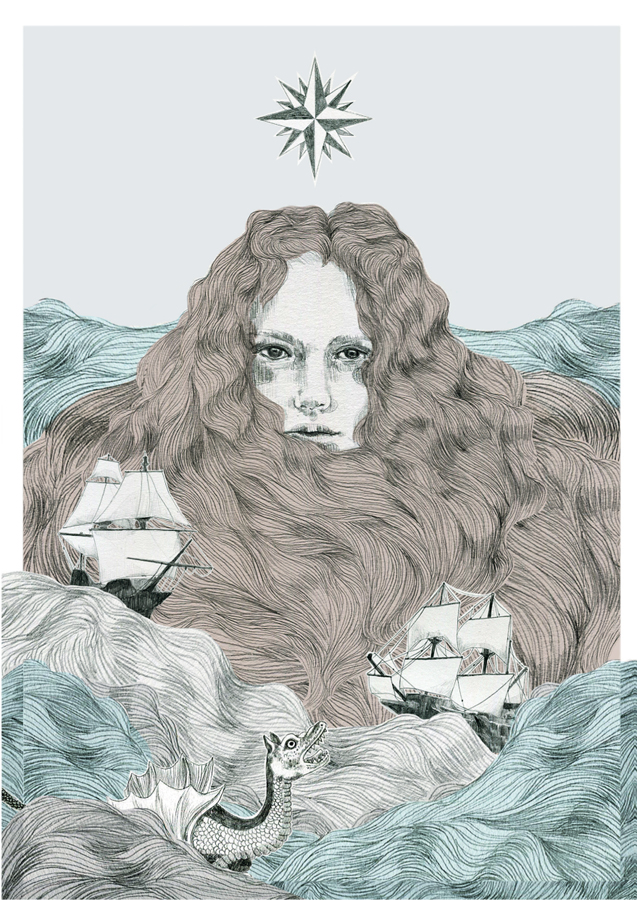

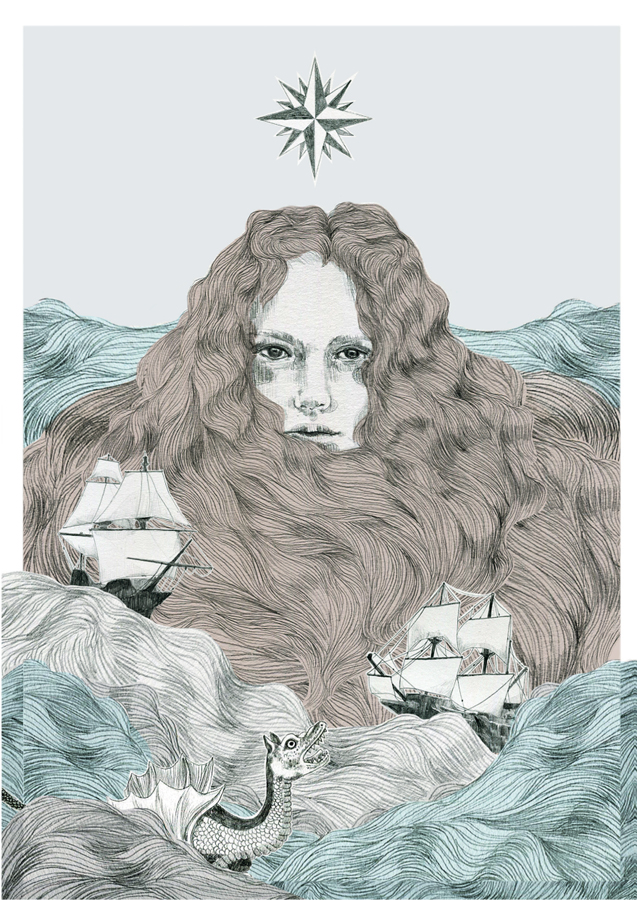

GRACE OMALLEY

race OMalley (15301603) called it maintenance by land and sea, but others disagreed with this 16th-century Irishwomans euphemistic framing of her profession. After all, piracy and fearsome, bloodthirsty piracy at that was piracy.

race OMalley (15301603) called it maintenance by land and sea, but others disagreed with this 16th-century Irishwomans euphemistic framing of her profession. After all, piracy and fearsome, bloodthirsty piracy at that was piracy.

Known variously as Granuaile, Grinne N Mhille or Grinne Mhaol, the pirate queen was labelled by her English adversaries a director of thieves and murderers at sea. As Tudor England attempted to conquer and control Ireland, and native clans feuded among themselves, Graces ultimate triumph was to rise above internecine conflict and secure the survival of herself and her family.

Born to a seafaring chieftain who ruled what is now part of County Mayo in the Irish province of Connaught, Grace was married off at 16 but was never going to be satisfied with domesticity and tending to her chieftain husbands home. Once married, she began her first foray into piracy on the Irish Sea, convincing some of her husbands men to join her in attacking merchant ships headed for nearby Galway. But when her husband died in battle, she returned to her fathers land to launch her career as a pirate in earnest. The legend of the Pirate Queen of Ireland was born.

Sifting myth from folklore, tradition and historical fact is not easy. Though not so well known outside her native land, Grace is lionized as an icon of Irish womanhood and commemorated on the sides of Irish ships, in folk songs and in James Joyces Finnegans Wake. Even today, Howth Castle in County Dublin lays an extra place at dinner for an unexpected visitor thanks to Grace.

After finding the family had locked its gates against her, she abducted their young heir as revenge, only returning him after she had extracted an eternal promise of hospitality.

For decades, her galleys would terrify traders and frustrate competing Irish clans as well as the English authorities. If any ship dared to reject her levies for safe passage in Clew Bay, where Graces crew sailed from her well-established strongholds, they would be ruthlessly plundered.

Grace led by example. Oral tradition holds that she gave birth on one of her ships. In Catholic custom, women had to be blessed after childbirth before they were allowed to re-enter church; Grace, far from land, was a long way from the nearest priest. But when her ship came under attack by Algerian pirates, neither religious faith nor post-childbirth fatigue could stop her from joining in. Leaving her newborn son below deck, she rallied her troops, firing a musket at her enemy with the declaration, Take this from unconsecrated hands!

But even as Grace terrorized the seas, Englands grip on Ireland was tightening. The disparate and disunited Irish clans would never effectively band together to fight off their English conquerors. When Sir Richard Bingham was appointed by the crown as the new governor of Connaught, he launched a campaign of aggression against Grace and every other chieftain in the land, declaring, The Irish were never tamed with words but with swords. By the time Grace hit her sixties, the Dorset-born military man had subdued and decimated the Irish clans; seized her ships, cattle and horses, and had her eldest son murdered. With Binghams warships docked in her beloved Clew Bay, she was effectively landlocked.

n the 19th century, Cuba was every bit the booming, prosperous Spanish colony. But its wealth had a dark side it flourished off the backs of thousands of slaves who worked on its plantations and in its sugar mills. By 1841, for the first time in Cubas history, a population census revealed that there were more slaves than white residents. Out of one million people, there were 436,000 slaves, 153,000 free people of colour and just 418,000 whites. The implications of the census were keenly felt among the Spanish authorities, who began to sense that the days of their grip on power demographically, at least were numbered.

n the 19th century, Cuba was every bit the booming, prosperous Spanish colony. But its wealth had a dark side it flourished off the backs of thousands of slaves who worked on its plantations and in its sugar mills. By 1841, for the first time in Cubas history, a population census revealed that there were more slaves than white residents. Out of one million people, there were 436,000 slaves, 153,000 free people of colour and just 418,000 whites. The implications of the census were keenly felt among the Spanish authorities, who began to sense that the days of their grip on power demographically, at least were numbered.

race OMalley (15301603) called it maintenance by land and sea, but others disagreed with this 16th-century Irishwomans euphemistic framing of her profession. After all, piracy and fearsome, bloodthirsty piracy at that was piracy.

race OMalley (15301603) called it maintenance by land and sea, but others disagreed with this 16th-century Irishwomans euphemistic framing of her profession. After all, piracy and fearsome, bloodthirsty piracy at that was piracy.