CONTENTS

The bit no one reads. But if you are reading this, I wanted to extend my thanks to:

Emma (my poor wife), for putting up with all of this.

Michael (my father-in-law), for his encouragement and translation services.

Servanne (my French friend), for her help with translating old newspapers.

Phil (my cycling friend), for his domestique services and cheery encouragement.

George, Joe and Harry (my sons), for their help and support. And, obviously, my mum (a pretty decent author herself).

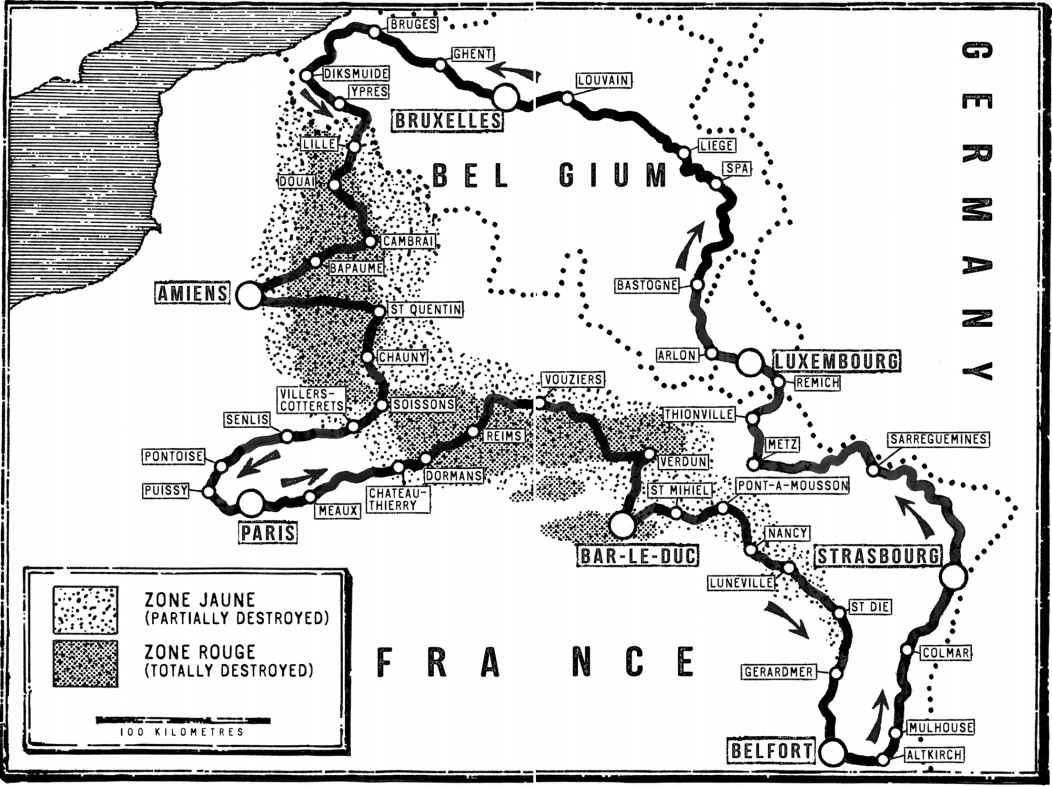

The Circuit des Champs de Bataille in 1919 was one of the most extraordinary bicycle races ever staged. In cataclysmic weather the riders raced across the battlefields of Belgium and northern France just a few months after the First World War had ended, enduring 300km-long stages, often on roads that no longer existed in the normal sense. It was such a tough race that it was never held again as a multi-stage event, and it all but disappeared from the records.

As a result, the primary source material is limited to brief reports in the organising newspaper, Le Petit Journal, reports in sports newspapers such as LAuto in France and Sportwereld in Belgium, and the briefest of mentions in a couple of cycling history books. The event was clearly so horrific for the organisers and most of the participants that they never mentioned it again.

With this in mind, I cannot know what the riders said, what they thought, or how they felt as they raced across the battlefields of Flanders and the Somme. So I have drawn on contemporary accounts of the battlefields in the immediate aftermath of the First World War in order to paint a picture of the conditions they endured. And I have drawn on accounts of bike racing immediately before and after the war to build up a picture of the men involved, the bikes they rode, and the tactics they used.

A full bibliography of sources can be found at the end of this book. The facts of the race are correct, but the dialogue and some scenes (in the lighter print) are the product of my imagination, based on what I know about those early racers. I hope you will forgive the small amount of literary licence employed to help bring these extraordinary men, and their astonishing achievements, to life.

Tom Isitt

London, 2017

2 May 1919

Lecomte took a lantern from a hook by the door, and stepped outside. Pulling his hat down against the flurries of sleet and rain borne on a biting wind, he peered into the night. Nothing. No sign. Where the hell were they? They should have been here hours ago. He lifted the lantern, as if hoping its modest glow would summon the riders from the gloom. Still nothing.

Out on the road, Charles Deruyter battled on. He was cold. Frozen to the core by the relentless wind and rain. And utterly exhausted. He had been riding since before dawn, and still had 70km to go. He hadnt seen any other riders for hours, and only one of the commissaires cars. All he had witnessed was the destruction and chaos of the battlefields. And, through the gathering darkness, hastily dug graves amongst the shell-holes and the wire. It was hard to pick a good line through the ruts and mud when you were shaking uncontrollably from the cold. The sleet whipped around him as he slipped and skidded on the treacherous muddy surface. Deruyters lonely suffering stretched to the endless bleak horizon; he wondered if feeling would ever return to his fingers and toes.

Returning to the light and warmth of the Caf de LEst in the centre of Amiens, Lecomte stamped his feet and shrugged off his thick overcoat. Il pleut encore, he muttered to his fellow Race Commissaires, gathered around a table near the fire. Degrain checked his pocketwatch and wondered, not for the first time, whether this race across the battlefields of the First World War, only a few months after the armistice, really was such a good idea.

A few miles behind Deruyter, Paul Duboc was locked in his own world of suffering. De-mobbed from the army only a few weeks earlier, the 35-year-old was a veteran of five Tours de France, and Deruyters senior by six years. Those five Tours meant he was no stranger to long, arduous race stages, but this was different. This was infinitely worse. He was chilled to the bone, and completely exhausted. Darkness was falling, and with no lights on his bike and no moonlight, Duboc would soon be riding blind, squinting through the rain and sleet to make out the road ahead. It was barely a road at all more an endless succession of smashed cobbles, potholes and shell craters, bridged with slippery wooden planks or partially filled in with whatever had come to hand.

Duboc cursed as his front wheel slid sideways and dumped him, for the umpteenth time, into the cold wet mud. Better that, he thought to himself, than to end up in one of the ditches either side. Since Cambrai he had become aware that the roadside ditches were filled with the most appalling detritus burned-out vehicles, rusting barbed wire, clothing, broken weapons, the bones of long-dead mules and horses. And all around were stacked piles of unexploded munitions, gathered up by the labour battalions clearing the battlefields. A dank, rotting smell of death and mud and rust oozed from the brutalised, lifeless earth.

While Deruyter and Duboc were struggling across the Somme, Van Lerberghe and Anseeuw, an hour behind, had sensibly teamed up and were negotiating their way through the ruins of Cambrai, now a sprawling pile of scorched masonry, charred wood and weeds. Van Lerberghe had ridden the ParisRoubaix race, subsequently nicknamed The Hell of the North, two weeks earlier so he had some inkling of what to expect. For the young Anseeuw, the utter desolation he saw here, and in the parts of Belgium they had already traversed, was profoundly shocking.

My God, muttered Anseeuw, look at this place! The Germans had set the town on fire when they pulled out six months earlier, leaving huge swathes of burned and collapsed houses. Here and there small shacks had been erected amongst the ruins by returning refugees, the only signs of life in this once-vibrant town.

The bastards didnt spare the matches, did they? answered Van Lerberghe as they slowed to negotiate another large, badly filled shell crater in the road. Up ahead, an elderly couple, dressed in shabby clothes and wearing rough wooden clogs, were pushing an old pram piled high with salvaged wood through the rain. Every few metres the uneven road surface would cause an avalanche of timber to cascade around their feet and they would stop and gather up their cargo. They paused in their Sisyphean labours to watch as Van Lerberghe and Anseeuw rode by.

Skirting the rusting remains of a tank on the outskirts of town, and a particularly pungent crater filled with God-knows-what, Van Lerberghe and Anseeuw exchanged weary glances and rode on, hoping to make it to Amiens at some point that night. But the weather was so bad, and the road so difficult, that it wasnt until after 1 a.m. that they made it to the finish of Stage 3, nearly 21 hours after they had set off from Brussels. The remaining riders still out on the road abandoned their attempts to get to the finish that evening, and spent the night shivering with cold in various trenches, dug-outs and pill-boxes on the Somme and Cambrai battlefields. For riders such as Maurice Brocco, de-mobbed from the army only a month before the race, this wasnt the first night he had spent trying to sleep in a cold, damp dug-out on a battlefield.