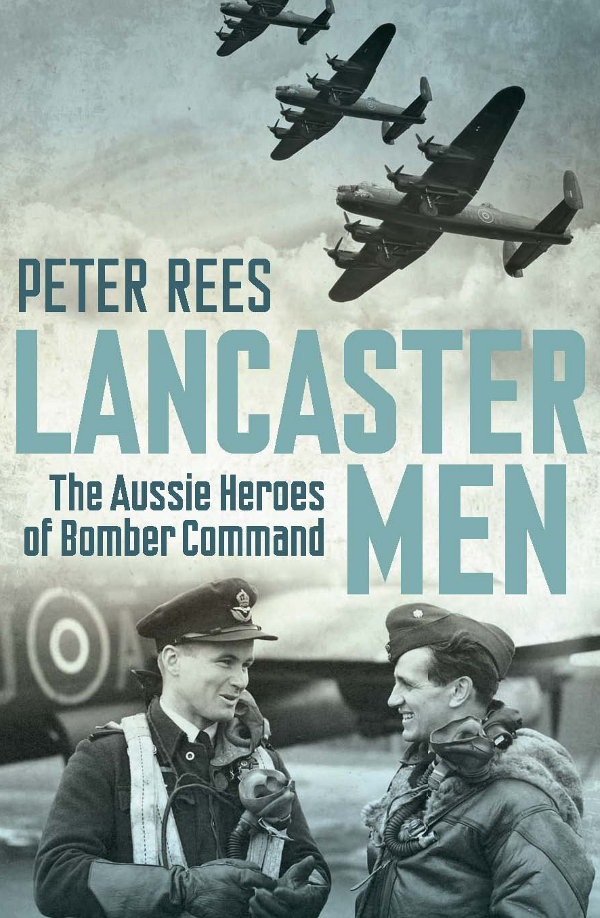

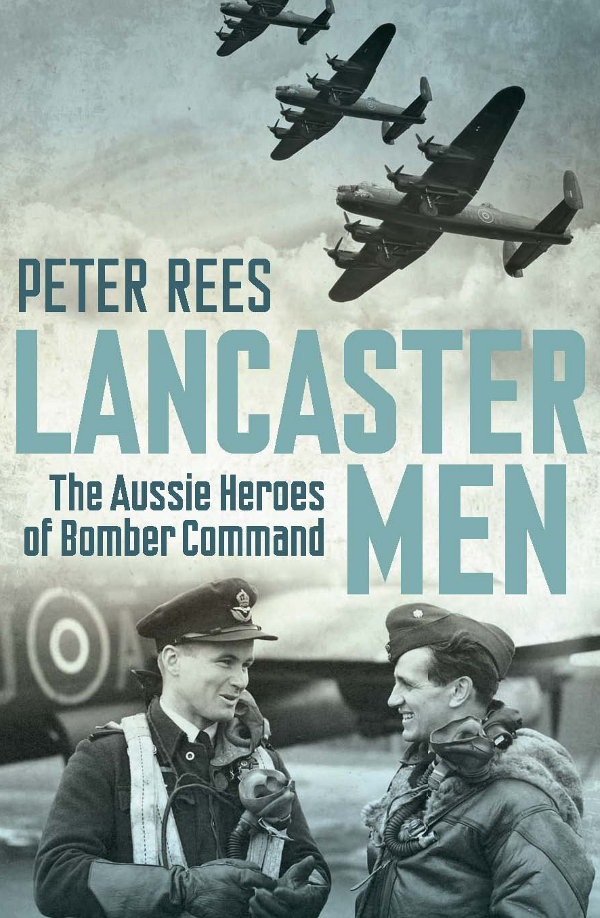

Peter Rees has been a journalist for more than forty years, working as federal political correspondent for the Melbourne Sun, the West Australian and the Sunday Telegraph. He is the author of The Boy from Boree Creek: The Tim Fischer Story (2001), Tim Fischers Outback Heroes (2002), Killing Juanita: A True Story of Murder and Corruption (2004), The Other Anzacs: The Extraordinary Story of our World War I Nurses (2008 and 2009) and Desert Boys: Australians at War from Beersheba to Tobruk and El Alamein (2011 and 2012).

First published in 2013

Copyright Peter Rees 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email: info@allenandunwin.com

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

Cataloguing-in-Publication details are available

from the National Library of Australia

www.trove.nla.gov.au

ISBN 978 1 74175 207 6

EISBN 978 1 74343 398 0

Internal design by Lisa White

Maps by Ian Faulkner

Set in 12/17 pt Minion by Midland Typesetters, Australia

Printed and bound in Australia by Griffin Press

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

In memory of my father, Ormonde,

who was a RAAF ground crew member in Australia.

And for Jack Wheildon, a Lancaster wireless operator/air gunner.

CONTENTS

For thousands of young Australian men, the outbreak of World War II in September 1939 meant a chance to fly. For many, it was the opportunity to fulfil a dream; for others, the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) was the least worst of the services they could join. This was a time when most Australians also felt loyalty to Britain.

The war meant that the United Kingdom was suddenly faced with a need for 50,000 aircrew a year; it could supply less than half this number itself. The solution Britain put to Australia, New Zealand and Canada was to jointly establish a pool of trained aircrew who could serve with the Royal Air Force (RAF) and other Commonwealth air forces. In December 1939 the four nations officially launched the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, known in Australia as the Empire Air Training Scheme (EATS).

Crucial to the scheme was recognition of the need to maintain a national identity for RAAF personnel sent to serve overseas. On 15 November 1939, Minister Robert Menzies had told the House of Representatives that the government would do its best to preserve the Australian character and identity of any air force that went abroad. It wanted the airmen to remain RAAF members, wear RAAF uniforms or a distinguishing badge, and be grouped into squadrons that would bear the name Australia. As far as possible, Australians would be led by Australians.

Article XV of the agreement allowed for some of these provisions, but RAF commanders were anxious to have all aircrews under their aegis. With Britain under growing pressure, there was little time for hashing out the finer points of the scheme. Australian trainees were needed urgently, and the first crews arrived in the UK in December 1940. The final text of the agreement between Britain and Australia called for eighteen RAAF squadrons to be formed within the next eighteen months. Their members would wear Australian uniforms, a senior RAAF officer would have access to the higher echelons of the RAF, RAAF personnel would be placed in RAF records and postings sections, and the two governments would continue to consult on major questions affecting the employment of RAAF personnel and squadrons overseas.

Even before the outbreak of war, about twenty per cent of Royal Air Force pilots came from the dominions and colonies. Since 1926, Australia had sent around ten trained pilots a year to serve with the RAF on short service commissions. Under the scheme approved they were supposed to join the RAAF Reserve on return to Australia, but most joined the RAF on permanent transfer. Other Australian nationals joined the RAF directly. In September 1939, about 450 Australians were serving with the RAF, mostly as pilots.

After EATS began in 1940, Australian recruits went through training programs that varied from thirty-six weeks for wireless operators/air gunners to fifty weeks for pilots. Waiting lists were long. By May 1942, just over 9500 aircrew were under instruction. At the time, the average cost of producing a trainee in Australia was 2200$144,000 in todays money. About 10,000 Australians did part of their training in Canada on the way to England. All costs connected with the training of aircrew, whether locally or in Canada, were met by Australia. More than 38,000 Australian aircrew participated in EATS.

After the United States joined the war in early 1942, RAF Bomber Command (including Australian, Canadian, New Zealand and South African squadrons) was supported in England by VIII Bomber Command of the US Army Air Force (USAAF), later redesignated the Eighth Air Force. The RAFs bomber workhorses at the start of the war included the Fairey Battle, Bristol Blenheim, Armstrong Whitworth Whitley and Handley Page Hampden/Hereford. They had been designed as tactical-support medium bombers, and they had neither the range nor the ordnance capacity for more than a limited strategic offensive. The Vickers Wellington, although limited by its two-engine configuration, was the only effective long-range bomber in the RAF inventory at the start of the war.

This changed with the advent of the British four-engined heavy bombers, the Short Stirling, Handley Page Halifax, Avro Manchester and the redoubtable Avro Lancaster. By late 1944, RAF Bomber Command alone could mount a raid by up to 1200 four-engined aircraft. It was composed of Nos. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 (Canadian) and 8 (Pathfinder Force) Group, each commanded by an air vice-marshal. Each group had its own headquarters planning staff and reported to Bomber Command Headquarters at High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire, run by Sir Arthur Harris, who in 1943 was made Air Chief Marshal.

Until June 1941, only one Australian Article XV squadron (as the EATS air units were known) had operated with Bomber Command455 Squadron, flying outdated Hampdens as part of 5 Group. The ground crew were mainly Australian, although there were many RAF supervisors and special tradesmen not sent from Australia. Operations continued until April 1942, when the squadron was transferred to Coastal Command.

In January 1942, 460 Squadron RAAF joined No. 1 Group, flying Vickers Wellingtons and later Avro Lancasters until the end of the war. The RAAFs 462 Squadron initially operated in the Middle East and did not join Bomber Commands No. 4 Group until August 1944, flying Halifax bombers. This squadron transferred to 100 Group RAFBomber Supportin December 1944 and operated there until the end of the war. In September 1942, 464 Squadron RAAF joined 2 Group, flying Ventura light bombers, and transferred with the rest of 2 Group to RAF Second Tactical Air Force in August 1943 in preparation for the invasion of Europe the following year.

Next page