Honours flowed for Waters after his death, ensuring a unique legacy, albeit belated. A commemorative stamp, an aerogram, parks and streets named after him, including at Inala, where he had lived for so many years. When the Leonard Victor Waters Memorial Park was officially opened at Boggabilla in October 1996, the mayor of Moree Plains Shire spoke of how Waters and his brother Jim were role models for all Australians. His hope was for reconciliation, and that we go into the new millennium as one community. A RAAF F-111C flypast broke the quiet as it ripped through the sky above before disappearing beyond the trees and across the Macintyre River to the east.

Among the mourners who had attended Waters funeral was Brett West, a Yamatji man and former jackeroo from Western Australia. At the time he was posted to 77 Squadron RAAF and was asked to represent the air force at the funeral. West did not know a great deal about Waters but the experience of attending the service and speaking to the Waters family affected him deeply. The penny droppedWaters story, he believed, could be the inspiration for Aboriginal kids to join the air force. I realised how much this bloke meant. From that moment I was determined to make the link for Indigenous kids, the link between them and the military. Its always pleased me that Indigenous kids are in awe of his story when I tell them about him.

In February 2009, a smoking ceremony and memorial service in honour of Waters was held at the Boggabilla memorial. Gladys spoke during the service of Waters love of flying, after which the family hymn Amazing Grace was sung. There was another nod to Waters: the president of the Moree RSL sub-branch delivered the Ode; perhaps this was atonement for what had befallen Waters at Moree during World War II. The service was a prelude to another later that day at Toomelah, where a memorial was unveiled not just to Waters but to all those local Indigenous men who fought for Australia, from the Boer war to the present.

*

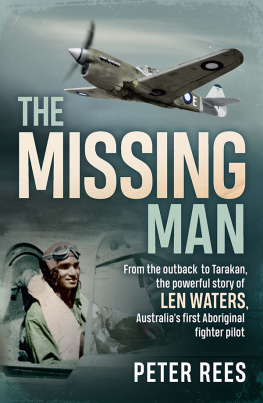

The RAAF dedicated an F/A-18A Hornet to Waters, painted in the colours of the Worimi people of the New South Wales central coast, the home of RAAF Base Williamtown. On the fighter were stencilled Waters name and the image of a wedge-tailed eagle, the bird of prey that had so fascinated him as it circled over the plains of his childhood country. A streak of dotted lines on the fuselage tracks the eagles flight with a sense of speed that mirrors the Hornet itself. The curved circles around the tail image and cockpit reflect a camping place, where clans people gather to rest, share stories and pass knowledge down from generation to generation. At the unveiling, the Chief of Air Force, Air Marshal Geoff Brown, AO, said Waters had been a pioneer and leader in every sense of the word. I hope that if he was here today, he would be honoured by the artwork that has been chosen.

Gladys presented the Australian War Memorial with Waters flying helmet, medals, escape map, pilots logbook, wings and earphones. In 2016 the AWM staged an exhibition, For Country for Nation, that recognised the contribution of Indigenous Australians to all wars in which the nation had been involved. Waters was an integral part of this exhibition.

It has been mooted that the new Sydney airport at Badgerys Creek be named in honour of Waters. Other names have been proffered but he has long been the sentimental favouriteIf only he had known.

In St George, a plaque on a sandstone plinth overlooking the Balonne River reaffirms Waters memory in a more down-to-earth way. It stands on a grassy bank alongside an identical memorial commemorating another RAAF hero from the St George district, Squadron Leader John Jackson, who was educated, ironically, at Brisbane Grammar Schoolthe same school that was so nearly Waters. Jackson ran the family grazing property at St George, bought his own aeroplane, and joined the RAAF Reserve before World War II saw him called up. He went on to fly in both the Middle East and the South West Pacific Area, where he led 75 Squadron RAAF. An ace, Jackson was credited with shooting down eight enemy aircraft in his Kittyhawk before he himself was shot down over Port Moresby on 28 April 1942.

Jackson and Waters came from vastly different backgrounds, one from wealth and the other from Aboriginal rural poverty, yet both were driven by the same desire to fly. Less than a metre apart, their monuments are angled towards each other as if in mutual respect. Gaining equality in life was Waters elusive dream; gaining that equality within the non-Indigenous community has been the same elusive goal of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders for two centuries.

In the words of Stan Grant, As a nation, we struggle to reconcile ourselves to our past and our place. Fundamental to the Australian story for the past century has been the Anzac legend, on which so much of the nations perception of itself has been built.

Whether subconscious or not, it became a story that excluded Indigenous Australiansso much so that former Queensland premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen could assert that Aboriginal people could not receive land rights, because they did not defend this country. This was uttered by a politician who neither flew a fighter plane nor served in World War II. Bjelke-Petersen struck no difficulty in obtaining his own civilian pilots licence.

With his front-line service in the RAAF, Waters challenges and loosens the white stranglehold on the Anzac legend. Although he was able to make a crack in this black ceiling, the same barrier became impenetrable once the war ended. Waters had glimpsed the future only to have it denied him. That was his tragedyand also Australias.

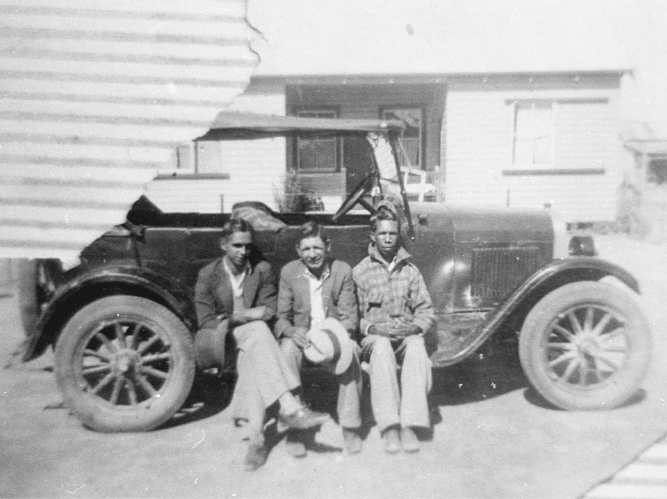

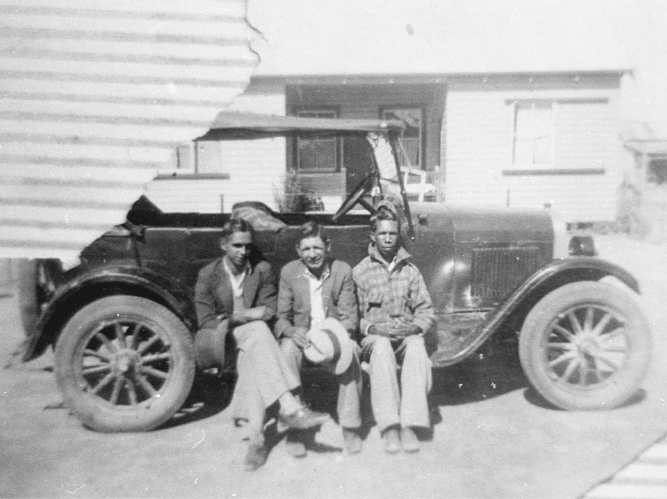

Don Waters put together a ring-barking team to work on farms after he moved to Nindigully. Taken at Box Flat, the photo shows Don, standing on the left. Son George is seated on the left, and son Jim is seated on the right of the group of three. (AIATSIS)

Grace Waters and son Barney Waters, then thirteen, at Nindigully. (AIATSIS)

Grace and Don Waters. (Kevin Waters)

Len Waters brother, Jim, on the right, with Nugget Wightman and Cecil Wightman, at Nindigully in the 1930s. (AIATSIS)

Nindigully school in the 1920s, shortly before Len Waters attended. (State Library of Queensland)

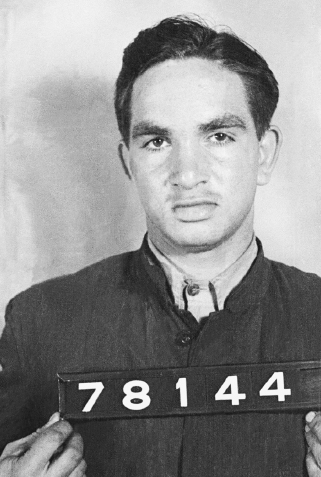

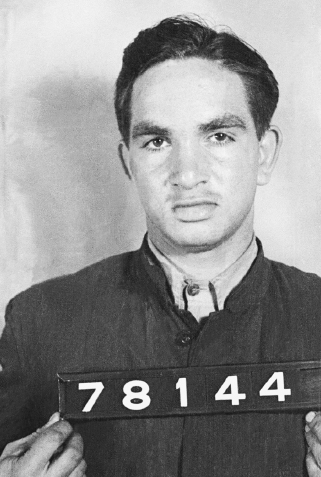

Len Waters on his enlistment in the RAAF in August 1942, aged eighteen. (NAA: A9301, 78144)

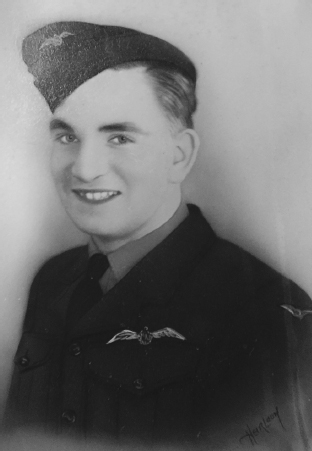

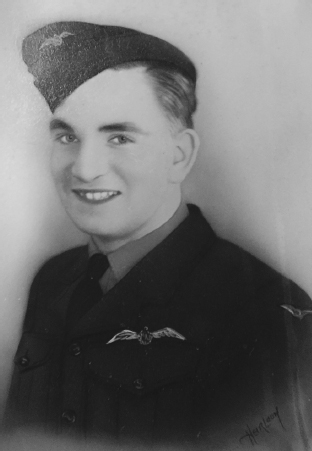

Len Waters being presented with his coveted wings on graduation day. (Gladys Waters)

Len Waters (second from left, rear) and fellow 2 OTU graduates. (Gladys Waters)

Next page