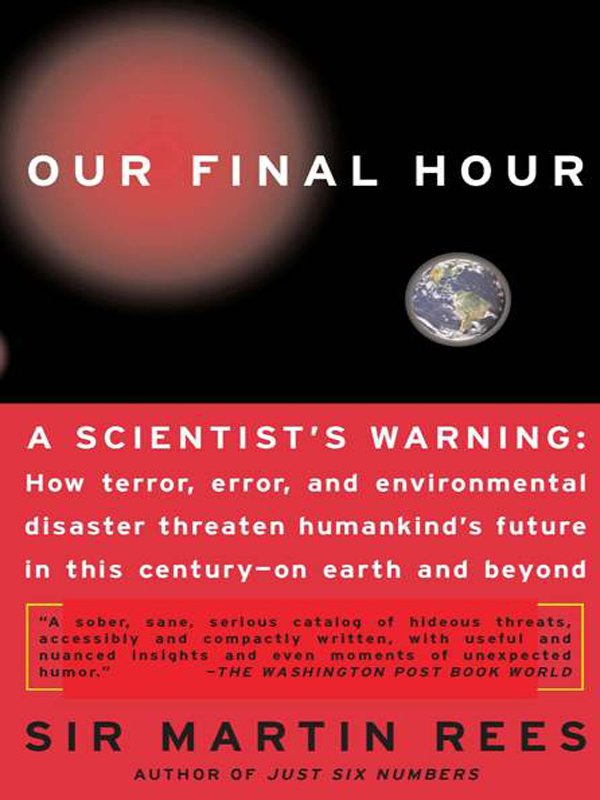

All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address Basic Books, 387 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016

PREFACE

SCIENCE IS ADVANCING FASTER THAN EVER, and on a broader front: bio-, cyber- and nanotechnology all offer exhilarating prospects; so does the exploration of space. But there is a dark side: new science can have unintended consequences; it empowers individuals to perpetrate acts of megaterror; even innocent errors could be catastrophic. The downside from twenty-first century technology could be graver and more intractable than the threat of nuclear devastation that we have faced for decades. And human-induced pressures on the global environment may engender higher risks than the age-old hazards of earthquakes, eruptions, and asteroid impacts.

This book, though short, ranges widely. Separate chapters can be read almost independently: they deal with the arms race, novel technologies, environmental crises, the scope and limits of scientific invention, and prospects for life beyond the Earth. Ive benefited from discussions with many specialists; some of them will, however, find my cursory presentation differently slanted from their personal assessment. But these are controversial themes, as indeed are all scenarios for the long-term future.

If nothing else, I hope to stimulate discussion on how to guard (as far as is feasible) against the worst risks, while deploying new knowledge optimally for human benefit. Scientists and technologists have special obligations. But this perspective should strengthen everyones concern, in our interlinked world, to focus public policies on communities who feel aggrieved or are most vulnerable.

I thank John Brockman for encouraging me to write the book. Im grateful to him and to Elizabeth Maguire for being so patient, and to Christine Marra and her colleagues for their efficient and expeditious efforts to get it into print.

OUR FINAL HOUR

1

PROLOGUE

THE TWENTIETH CENTURY BROUGHT US THE BOMB, and the nuclear threat will never leave us; the short-term threat from terrorism is high on the public and political agenda; inequalities in wealth and welfare get ever wider. My primary aim is not to add to the burgeoning literature on these challenging themes, but to focus on twenty-first century hazards, currently less familiar, that could threaten humanity and the global environment still more.

Some of these new threats are already upon us; others are still conjectural. Populations could be wiped out by lethal engineered airborne viruses; human character may be changed by new techniques far more targeted and effective than the nostrums and drugs familiar today; we may even one day be threatened by rogue nanomachines that replicate catastrophically, or by superintelligent computers.

Other novel risks cannot be completely excluded. Experiments that crash atoms together with immense force could start a chain reaction that erodes everything on Earth; the experiments could even tear the fabric of space itself, an ultimate Doomsday catastrophe whose fallout spreads at the speed of light to engulf the entire universe. These latter scenarios may be exceedingly unlikely, but they raise in extreme form the issue of who should decide, and how, whether to proceed with experiments that have a genuine scientific purpose (and could conceivably offer practical benefits), but that pose a very tiny risk of an utterly calamitous outcome.

We still live, as all our ancestors have done, under the threat of disasters that could cause worldwide devastation: volcanic supereruptions and major asteroid impacts, for instance. Natural catastrophes on this global scale are fortunately so infrequent, and therefore so unlikely to occur within our lifetime, that they do not preoccupy our thoughts, nor give most of us sleepless nights. But such catastrophes are now augmented by other environmental risks that we are bringing upon ourselves, risks that cannot be dismissed as so improbable.

During the Cold War years, the main threat looming over us was an all-out thermonuclear exchange, triggered by an escalating superpower confrontation. That threat was apparently averted. But many expertsindeed, some who themselves controlled policy during those yearsbelieved that we were lucky; some thought that the cumulative risk of Armageddon over that period was as much as fifty percent. The immediate danger of all-out nuclear war has receded. But there is a growing threat of nuclear weapons being used sooner or later somewhere in the world.

Nuclear weapons can be dismantled, but they cannot be uninvented. The threat is ineradicable, and could be resurgent in the twenty-first century: we cannot rule out a realignment that would lead to standoffs as dangerous as the Cold War rivalry, deploying even bigger arsenals. And even a threat that seems, year by year, a modest one mounts up if it persists for decades. But the nuclear threat will be overshadowed by others that could be as destructive, and far less controllable. These may come not primarily from national governments, not even from rogue states, but from individuals or small groups with access to ever more advanced technology. There are alarmingly many ways in which individuals will be able to trigger catastrophe.

The strategists of the nuclear age formulated a doctrine of deterrence by mutually assured destruction (with the singularly appropriate acronym MAD). To clarify this concept, real-life Dr. Strangeloves envisaged a hypothetical Doomsday machine, an ultimate deterrent too terrible to be unleashed by any political leader who was one hundred percent rational. Later in this century, scientists might be able to create a real nonnuclear Doomsday machine. Conceivably, ordinary citizens could command the destructive capacity that in the twentieth century was the frightening prerogative of the handful of individuals who held the reins of power in states with nuclear weapons. If there were millions of independent fingers on the button of a Doomsday machine, then one persons act of irrationality, or even one persons error, could do us all in.