Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Published by Da Capo Press, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Da Capo Press name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Editorial production by Lori Hobkirk at the Book Factory Print book interior design by Cynthia Young at Sagecraft

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data has been applied for.

I ts a Saturday evening in summer 1982. I am seventeen years old, sitting in a porn cinema in Londons Soho. Im with five teenage friends, male and female, and were passing out cans of cheap lager from supermarket bags stashed between our feet.

The tiny theater smells of last weeks cigarettes, disinfectant, and bodies. We are not alone. In the shadows we can see a homeless man slumped across two seats, fast asleep and snoring. Behind us, someone is coughing loudly, as a cloud of dope smoke wafts down the aisle.

One weekend a month, this cinema abandons its timetable of adult movies to show Led Zeppelins The Song Remains the Same. The film isnt available on video yet, and very few people we know own a VCR anyway.

Listening to Led Zeppelin in 1982 is a peculiar, often isolating pastime. The band broke up two years earlier following the death of drummer John Bonham, and their lead singer, Robert Plant, has just released his first solo record.

The compact disc is about to arrive, and were in a brand new decade with brand new groups. Nobodys supposed to care about Led Zeppelin anymore. And yet here we are.

Weve already watched forty minutes of the movie. Rock and Roll, Celebration Day, and the rest have been delivered with fast-moving close-ups of Robert Plant and guitarist Jimmy Page, swaggering and peacocking across the stage of New Yorks Madison Square Garden. Then, suddenly, the film cuts to a dressing room somewhere in America.

It doesnt take long to notice this backstage anteroom, with its strip lights and drab paintwork, is about as glamorous as the dressing rooms in most British provincial civic halls. But all that matters is its backstage at a Led Zeppelin concert.

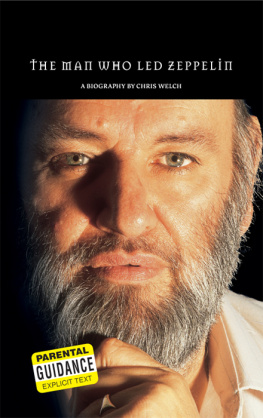

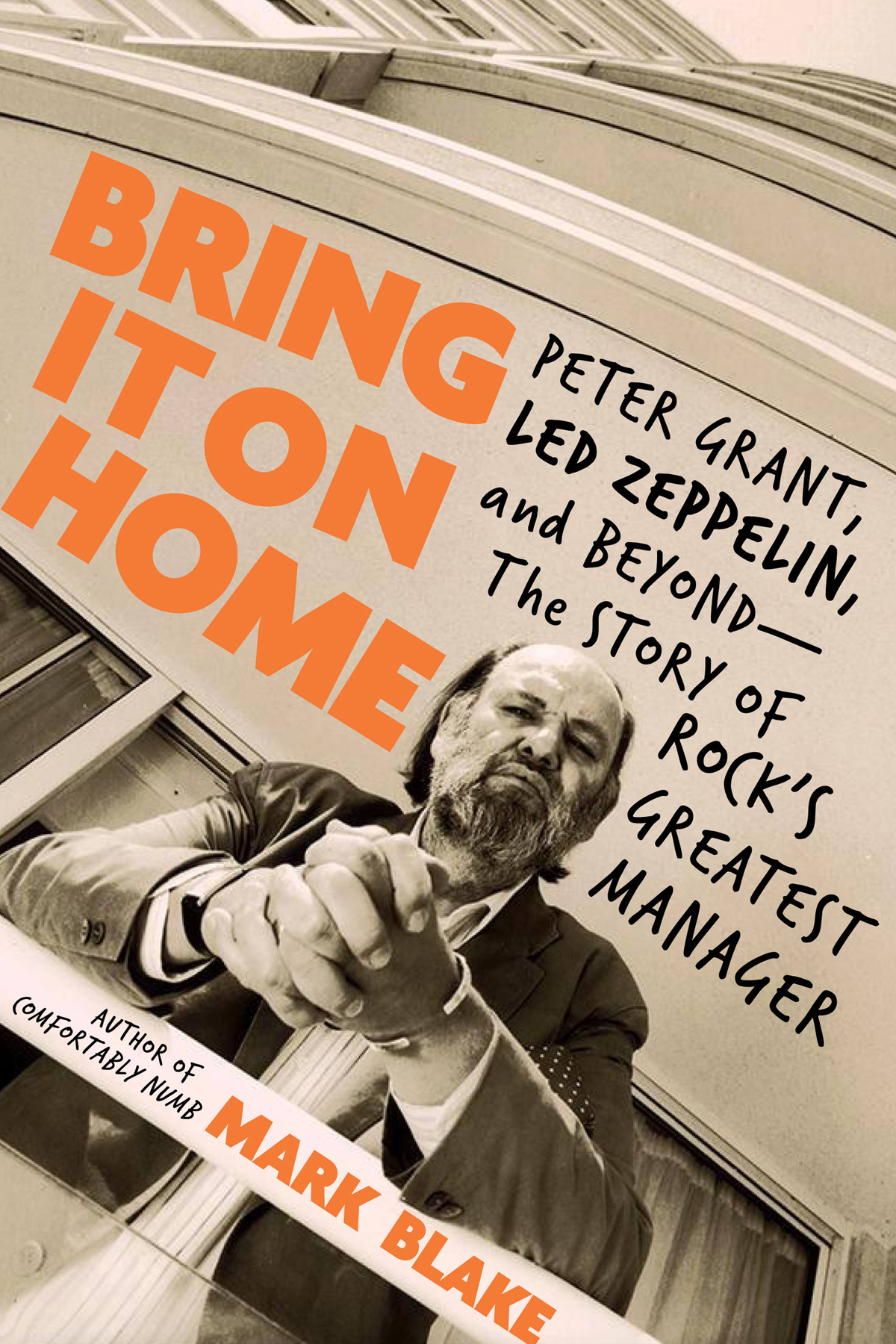

On screen, theres an argument taking place between an American, whose clothes and haircut suggest hes some kind of authority figure, and an enormous, bearded Englishman, whom we recognize as Zeppelins manager Peter Grant. He looks like a gypsy pirate and sounds like he should be throwing drunks out of pubs in Soho. Which isnt far off what he once did for a living.

Weve already seen Grant briefly at the beginning of the film: playing a Mafia-style capo in one of the movies awkward fictional sequences, but that was a silent role.

In the backstage scene, the rolling cadence of Grants South London accent and his scattergun profanities (Dont fucking talk to him! Its my bloody act!) stay with us long after the film has ended. Led Zeppelin is the star of The Song Remains the Same. Their manager is its unsung hero.

Peter Grant always looked like hed wandered in off the set of a movie and chosen to remain in character. Unbeknown to us then, hed been an actor in a past life. The wild hair and beard, the antique rings, and the silk scarves were part of his costume.

Grant came from the preSecond World War era, a world of variety theater and gramophone records, long before television and rock n roll. He was a generation older than Led Zeppelin.

Londons West End had been Peter Grants domain in the late fifties and early sixties. It hadnt changed much by 1982. Twenty-first-century Soho, with its al fresco dining and cosmopolitan bar culture, wasnt even a developers dream then.

After the film, we left the cinema and headed for the nearest pub. Turn down any Soho alley in the early eighties and you entered a rabbits warren of peepshows, clip joints, and what tabloid newspapers called dirty book shops. It wasnt so different in Grants day.

Less than five minutes walk from the cinema is Old Compton Street. Here, the twenty-one-year-old Peter Grant took the tickets at the 2is coffee bar, while British rock n roll wannabes played on a stage made from milk crates in the cellar. Nearer still, on Wardour Street, had been the Flamingothe all-night jazz and blues club where Grant policed the door in the era of Georgie Fame and the Blue Flames.

From the Flamingo, you could be at what was once Murrays Cabaret Club on Beak Street in less than ten minutes. In the late fifties, members of the royal family and East End gangsters sipped champagne side by side at Murrays, while Grant stood in the doorway in his concierges cap and uniform, ordering cabs for crooks and their showgirl mistresses.

In the early sixties, when hed worked for Sharon Osbournes fatherthe promoter Don ArdenGrant had been a familiar presence in the music publishers offices on nearby Denmark Street and at venues such as the original Marquee and the 100 Club.

When the original American rock n rollers Gene Vincent and Chuck Berry first came to Britain, Grant was there, driving them between gigs and collecting their fee. Later, after homegrown pop acts such as the Animals and the Yardbirds came of age, Grant was there again, shaking down rogue club owners who tried to cheat them out of their money.

Like a giant, moustachioed Zelig, Peter Grant was always somewhere in the picture as this ramshackle, fly-by-night operation evolved into the modern-day music business.

Ten years after first seeing The Song Remains the Same in a West End porn cinema, I was at the Marquee when word spread that Led Zeppelins fabled ex-manager was in the building. All heads turned away from the stage toward the tall, bearded gentleman standing near the bar. Grants costume had changed: the scarves and rings replaced by a somber business suit, and there was much less of him than there had been in the movie.

By now, Id convinced a couple of bottom-rung-of-the-ladder music magazines to let me write for them. They were generous with concert tickets and free records, less so with paychecks. But after the show I was allowed entry to the Marquees green room, where I was introduced to Grant. Out of nowhere, he asked my opinion of the group wed just seen.

Was there a right answer, I wondered? I told him I wasnt sure. He told me he wasnt either, but that the guitarist was good. I wondered what it must be like trying to judge any new guitarist when the yardstick was Jimmy Page. He sounded just like he did in