Table of Contents

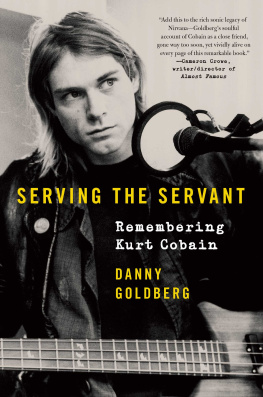

To Rosemary Carroll and our children, Katie Goldberg and Max Goldberg

And to two great friends who have encouraged me for many decades, Michael Des Barres and David Silver

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks to Rosemary for enduring my many mood swings and for her excellent advice. She prevented numerous errors but deserves none of the blame for those that remain.

Thanks to my agent, Steve Wasserman, who never wavered.

At Gotham, thanks to Bill Shinker for taking the plunge; to my editor, Lauren Marino, for her advocacy, guidance, and patience; Brianne Ramagosa; and to copy editor supreme, Craig Schneider.

My assistant, Laura Benanchietti, was indispensable in countless ways. My colleagues at Gold Village Entertainment, Jesse Bauer, Brady Brock, and Cyndi Villano, have also been great sources of support.

Steve Earles advice during the writing is yet another example of the fact that he manages my career at least as much as I manage his.

Eric Alterman, Sara Davidson, Leigh Haber, Robert Christgau, Michael Des Barres, and David Silver all gave valuable advice.

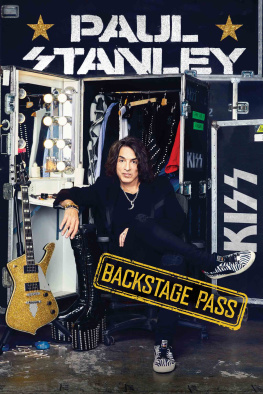

I am very grateful to Lee Abrams, Susan Blond, Howard Bloom, Michael Des Barres, B. P. Fallon, Steve Earle, Les Garland, Debbie Gold, Patrick Goldstein, Robert Hilburn, Kid Leo, Kenny Laguna, Mitchell Markus, Mario Medius, Krist Novoselic, Steve Paul, Jonny Podell, Steve Popovich, Bonnie Raitt, Vin Scelsa, Bonnie Simmons, Gene Simmons, Patti Smith, Robert Smith, Larry Solters, Mark Spector, Paul Stanley, Burt Stein, Norm Winer, Peter Wolf, and Jordan Zevon for providing me with their recollections and insights, and to Courtney Love for her friendship.

I was aided greatly by the reading of Carrie Borzillos Nirvana: A Day by Day Eyewitness Chronicle and Jim Ladds Radio Waves, and repeated viewing of Martin Scorseses film No Direction Home.

My rock and roll taste was formed at Fieldston High School by friends including Judy Barnett, Bob Bearnot, Mark Brownstone, June Christopher, David Comins, Karen Gilbert, Joel Goodman (BFF), Karen Hawes, Gil Scott Heron, Billy Horowitz, Joanne Kinoy, Judy Kinoy, Peter Kinoy, Dickie Kleinberg, John Krich, Alex Richman, Laura Rosenberg, Susan Solomon, Robin Scott, and John Scott, as well as two non-Fieldston friends, Val Sowall and Tom Lubart. My brother Peter Goldberg turned me on to both the Kinks and the Animals.

Artemis Records existed because Michael Chambers believed in it and in me. Also indispensable to Artemis were Patrick Panzarella, Ray Chambers, and Daniel Glass.

Eternal thanks to my guru and teacher Hilda Charlton and to my sister Rachel Goldberg for the example she sets in resolving conflicts.

And thanks to every artist I ever met, worked with, or was inspired by and to the formless mysterious force that created rock and roll.

INTRODUCTION

SECRETS OF THE ROCK AND ROLL BUSINESS

There arent any secrets, Atlantic Records president Jerry Wexler growled at me, as if I were the stupidest person he had ever met. I was nineteen and it was the winter of 1969, more than thirty-five years before Wexler would be immortalized by Richard Schiffs portrayal of him in the movie Ray. I was writing a column for the weekly trade magazine Record World when Wexler had asked one of his executives, Danny Fields, to gather a group of young journalists who wrote about rock and roll. The real Wexler was far more imposing than the cinematic version. He was broad-shouldered, with a salt-and-pepper beard and sunken eyes that gave him the look of an Old Testament prophet. He had a thick Bronx accent, an intimidating intellect, and the ultimate rock and roll and R&B pedigrees.

Some months earlier, at the storied Greenwich Village nightclub the Village Gate, I had seen a talented R&B singer named Judy Clay dedicate her hit, Storybook Children, to Wexler, who stood up and waved with an understated noblesse oblige.

I had no idea what a record company president did, but I was stunned that such a soulful singer would publicly acknowledge a mere businessman. I soon discovered that Wexler had also worked with Otis Redding, Aretha Franklin, and Sam and Dave, and had been the person at Atlantic who actually signed Led Zeppelin.

My awe at Wexlers rsum was reinforced by seeing his house in Great Neck, Long Island, which had an entire room filled with gold records and a living room with original Lgers. Amid thick marijuana smoke, Wexler played records on his state-of-the-art stereo, alternating an acetate of a forthcoming Delaney and Bonnie album with the Beatles Abbey Road. It was a relief to know that even an insider like Wexler was a Beatles fan. Those guys sure know what theyre doing, he sighed, listening to the end of Carry That Weight. During a moment between songs, in a lame attempt to enter the conversation, I asked Wexler if he was going to an upcoming conference on the music business. I never go to those things, he snarled. The premise is that you can go there and learn secrets. First of all, there arent any secrets. He paused dramatically and then, with a wolfish grin, concluded, And second of all, if there were any secrets, we wouldnt tell them.

Over the next several decades I would come to understand what he meant. Although I never came close to equaling Wexlers historical contribution to the music business, I was lucky enough to find myself in many situations that would make rock history. I had a press pass to the Woodstock Festival. I worked for Led Zeppelin from 1973 to 1976, first as their publicist and later as vice president of their record company. I managed Nirvana when Nevermind came out and Bonnie Raitt when she won four Grammys. I did PR for Kiss and Electric Light Orchestra. I worked closely with Bruce Springsteen on the No Nukes movie. At the peak of Fleetwood Macs popularity I helped launch Stevie Nickss solo career. And twenty-four years after meeting Wexler I was given his old job as president of Atlantic Records. What few secrets there were could not be of any help to anyone else. But there were stories.

I cant be objective about the music business. I know it hurt a lot of people; artists were often lied to, royalties werent always paid, bad people sometimes got promoted while good ones were fired. Drugs, misogyny, and death stalked rock and roll. A lot of shlock was produced. A lot of pretense masked shallow, materialistic quests for fame and money. Its not like I dont know these things and its not that I mind writing about them. Its just that the part of the music business I know best, the rock and roll business, also produced and popularized a lot of music that I love. And it gave me and a lot of my friends a place in the world.

One nonsecret of the rock business is the intertwined nature of art and money. No one became a rock star by accident or against their will. Bob Dylans memoir, Chronicles, begins not with a reference to Woody Guthrie or Allen Ginsberg, but with a meeting Dylan had as a young man with music publisher Lou Levy. Levy showed him the studio on the west side of Manhattan where Bill Haley and His Comets had recorded Rock Around the Clock, which is widely considered the song that made rock and roll music a part of mainstream American culture.

Dylan did inject a folk music aesthetic into the commercial rock culture that existed. Steve Earle, who grew up in Texas in the 1960s, saw folk music as the vehicle that brought art into rock and roll. The great beatnik poet Allen Ginsberg saw Dylans song A Hard Rains A-Gonna Fall as the passing of the torch of Bohemian illumination and self-empowerment. The ideals and aesthetics that informed folk music of the early and mid-1960s would continue to be present in varying degrees in the minds of many successful rock artists for decades to come.