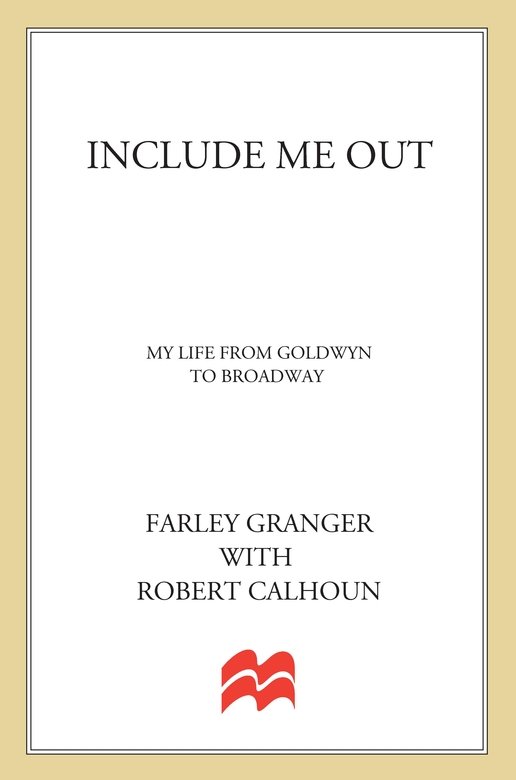

To Lawrence Malkin, whose generosity of spirit, intelligence, good humor, and willingness to share his expertise as a professional writer made this collaboration possible.

Acknowledgments

To Diane Reverand, our editor, who missed nothing: our excess of, or lack of, information, opinion, style, continuity, and taste.

To Philip Spitzer, our agent, who patiently resumed his efforts on our behalf after a twelve-year hiatus and found, with his usual dispatch, the right people. To Jay Julien, our lawyer/manager, who has been our rock and the repository of our trust for thirty years.

To Frederick Kaufman, whose personal and professional opinion has been cheerfully given, eagerly sought, and happily received.

To Shirley Kaplan, who has never wavered in her enthusiastic support for this project.

To Linda and Patrick Pleven, who assisted on every how-to problem, willingly, cheerfully, and lovingly, every time we called upon them.

To Neila Smith Kennedy, who has been there with and for us from day one, twelve years ago.

To Eddie Muller and the San Francisco Film Noir Festival.

To Regina Scarpa, our associate editor, whose unflappable good humor and good sense saved many fraught moments from descending into disaster.

Special Thanks

To Samuel Goldwyn, Jr.

To Jane Klane and the Museum of Television and Radio; to the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts and its staff at Lincoln Center; and to the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

I never thought that one of Goldwyns most famous malapropisms would apply to me so accurately that I would one day quote it as the title for my memoir.

Im sure he was smart enough to realize that celebrity and talent are not necessarily one and the same. I dont know if he was sensitive enough to realize I was smart enough to have figured this out from the beginning. I wanted to develop my talent. I had no interest in becoming a household name or in playing by the rules of the game to become a movie star. When I bought out my contract, Goldwyn thought I was escalating my rebellion to a crazy level for some ulterior motive. I was following my heart and doing what I had to do.

It worked. To this day I cannot forget the thrill of getting my first laugh onstage, the joy of dancing and singing Shall We Dance? onstage with Barbara Cook, the sense of accomplishment when the curtain came down on the plays with the National Repertory Theatre. I loved the excitement of creating a character in a new play with the playwrights collaboration, and I will never forget the pride and happiness I felt for receiving an award for doing something I enjoyed so much.

I owe Sam Goldwyn for creating the circumstances that forced me to include myself out. Thanks, Mr. G.

I t was 1943. America was at war. I was a healthy seventeen-year-old high school student, halfway through my senior year. My future was clear: I would graduate and when I turned eighteen in July, I would join whatever branch of the armed forces most of my buddies were choosing. Thats exactly what happened, with one exception: I became a movie star first.

As a clerk in the unemployment office in North Hollywood, my dad was used to seeing actors when they came in every week to collect their checks. There was the occasional grand one like Adolphe Menjou, who arrived in a chauffeured limousine each week to pick up his check, but most of them were just ordinary out-of-work actors waiting for their next paying job to come along. Dad became friendly with an actor who was far from ordinary. It was Harry Langdon, who had been one of the Big Four, Hollywoods most beloved stars during the silent film era, along with Harold Lloyd, Buster Keaton, and Charlie Chaplin. Chaplin was the only one of the four who survived the transition to talkies. The others had fallen on differing degrees of hard times. Keaton and Lloyd eventually survived more successfully than Mr. Langdon. My dad had great admiration for his new friend, and eventually felt free enough with him to ask his advice about my dream of becoming an actor.

After mulling it over for several weeks, Langdon told Dad about a small showcase theater on Highland Avenue in Hollywood that was run by Mary Stewart, a little-known actress with a lot of money and some talent. There was no permanent company, no set schedule. Each production that Miss Stewart managed to put on consisted of a pickup group of actors, most of them amateurs who would work for nothing in order to get the experience, and the credit, not to mention an opportunity to live the dream of being discovered.

She was currently seeing young actors for The Wookie, an English play about Londoners during the blitz in World War II. At dinner that evening, my dad told us about it, and my mom agreed to take time off from her job at the five-and-ten-cent store to drive me to the theater the next day to find out how to go about trying out for a part.

The next afternoon, Mom got off early and picked me up at school, and offwe went. The theater was a nondescript auditorium with folding chairs, much like many of todays Off-Broadway theaters. Lucky for me, they were having an open audition, one to which amateurs, actors who were not yet members of Actors Equity, were welcomed. The stage manager gave me some pages from different scenes and told me to go study them and come back in an hour. I returned to read for Miss Stewart and the director using a Cockney accent, which had to be awful, because it was something Id just made up after reading the scenes. I had no frame of reference for the accent other than the few English movies Id seen. There was a long silence after I finished, and then what sounded like a whispered argument between Miss Stewart and the director. After what seemed like an eternity, Miss Stewart came to the edge of the stage to congratulate me on getting the part. Even though in my navet I had felt since childhood that it was my destiny to be an actor one day, I was in a state of shock when it happened.

At our first read-through of The Wookie, I met the rest of the cast, including Percival Vivian, our English director, who was also playing the leading man. We all, with the exception of Miss Stewart and Mr. Vivian, had to double and triple parts. Three of the actors were old-timers who had been extras in the movies for years and regulars in Mary Stewarts productions. There was a young boy who was a brand-new member of Actors Equity. The last two members of the company, a pretty young redhead named Connie Cornwall and I, had never set foot on a real stage before.

Miss Stewart was grand, but she could not have been nicer to everyone. Percy, the director, often seemed as if he had it in for me. I had no idea why. Since he said he had been in London during the blitz, I hung on his every word as if they were graven in stone.

After three weeks of rehearsing scenes, it was time to add the costumes, lighting, and sound effects. Technical rehearsals were very exciting, with the sounds of bombs going off and sirens and shouting all over the place. I had to run on and off, change coats, and return to the stage as someone else. It was exhilarating. After the final tech rehearsal, Percy called me over and said, Good show, young man. Be at the dress rehearsal tomorrow a wee bit early, would you? Before I could reply, he turned and walked off. I was so pleased by his compliment that I didnt ask why. I couldnt wait to comply.

At the call for the dress rehearsal, I was in my costume, waiting outside his dressing room, when he arrived. He said he wanted to show me how to make up. I was very excited to get this chance to learn something professional. He did a full character makeup with heavy lines for age and big dark circles under my eyes. I thought I looked just terrific. He had turned me into a character man! My favorite actors were always people like Frank Morgan and Bert Lahr in The Wizard of Oz, never the young leading men. After thanking him profusely, I ranback to my dressing room so that everyone could admire the new me. No one even looked up.