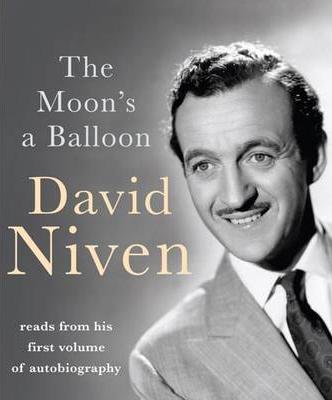

David Niven

The Moons a Balloon

An autobiography

1971, EN

Reminiscences by David Niven.

Takes readers back to David Niven's childhood days, his humiliating expulsion from school and to his army years and wartime service. After the war, he returned to America and there came his Hollywood success in films such as "Wuthering Heights" and "Around the World in 80 Days".

About the Author

David Niven was born in London in 1910 and died in 1983. He was seen as the quintessential English gent.

Table of contents

INTRODUCTION

Who knows if the moons a balloon, coming out of a keen city in the sky-filled with pretty people? And if you and I should get into it, if they should take me and take you into their balloon, why then wed go up higher with all the pretty people than houses and steeples and clouds: go sailing away and away sailing into a keen city which nobodys ever visited, where its always Spring and everyones in love and flowers pick themselves.

E.E. Cummings

Evelyn Waugh penned these words: Only when one has lost all curiosity about the future has one reached the age to write an autobiography.

It is daunting to consider the sudden wave of disillusionment that must have swept over such a brilliant man and caused him to write such balls. Nearer the mark, it seems to me, is Professor John Kenneth Galbraith of Harvard University who wrote: Books can be broken broadly into two classes: those written to please the reader and those written for the greater pleasure of the writer. Subject to numerous and distinguished exceptions, the second class is rightly suspect and especially if the writer himself appears in the story. Doubtless, it is best to have ones vanity served by others; but when all else fails, it is something men do for themselves. Political memoirs, biographiesof great business tycoons and the annals of aging actors sufficiently illustrate the point. The italics are mine.

I apologise for the ensuing name dropping. It was hard to avoid it. People in my profession, who, like myself, have the good fortune to parlay a minimal talent into a long career, find all sorts of doors opened that would otherwise have remained closed. Once behind those doors it snakes little sense to write about the butler if Chairman Mao is sitting down to dinner.

David Niven

Cap Ferrat A.M.

ONE

N essie, when I first saw her, was seventeen years old, honey-blonde, pretty rather than beautiful, the owner of a voluptuous but somehow innocent body and a pair of legs that went on for ever. She was a Piccadilly whore. I was a fourteen-year-old heterosexual schoolboy and I met her thanks to my stepfather. (If you would like to skip on and meet Nessie more fully, she reappears on page 41.)

I had a stepfather because my father, along with 90 per cent of his comrades in the Berkshire Yeomanry, had landed with immense panache at Suvla Bay. Unfortunately, the Turks were given ample time to prepare to receive them. For days, sweltering in their troopships, the Berkshire Yeomanry had ridden at anchor off shore while the High Command in London argued as to the best way to get them on the beach. Finally, they arrived at their brilliant decision and the troops dutifully embarked in the ships whalers. On arrival they held their rifles above their heads, cheered, and gallantly leaped into the dark waist-high water. A combination of barbed wire beneath the surface and machine guns to cover the barbed wire, provided a devastating welcome.

Woodpigeons were calling on a warm summer evening and my sister, Grizel, and I were swapping cigarette cards on an old tree trunk in the paddock when a red-eyed maid came and told us our mother wanted to see us and that we were not to stay too long.

After a rather incoherent interview with our mother, who was French, and had trouble explaining what missing meant, we returned to the swapping of cigarette cards and resumed our perusal of endless trains lumbering along a distant embankment loaded with guns and waving young men1915. I am afraid my fathers death meant little or nothing to me at the time; later it meant a great deal. I was just five years old and had not seen him much except when I was brought down to be shown off before arriving dinner guests or departing fox-hunting companions. I could always tell which were which because the former smelled of soap and perfume and the latter of sweat and spirits.

I lived with Grizel in a nursery presided over by a warm enveloping creature, Whitty.

Rainy days were spent being taught Highland reels by a wounded piper of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, and listening to a gramophone equipped with an immense horn. Our favourite record had The Ride of the Valkyrie on one side and, on the other, a jolly little number for those days, called The Wreck of the Troopship. We were specially fascinated by the whinnying of the horses as the sharks moved in (the troops were on the way to the South African War).

Occasionally, I was taken to the hospital in Cirencester to do my bit. This entailed trying not to fidget or jump while VADs practised bandaging any part of me they fancied.

The war days sped by and the house in Gloucestershire was sold. So, too, was one we had in Argyllshire. Everyone, my mother included, was under the misapprehension that my father was very rich. He had cheerfully gone off to war like a knight of old, taking with him as troopers his valet, his under-gardener and two grooms. He also took his hunters, but these were exchanged for rifles in Egypt en route and my father, his valet and one groom were duly slaughtered.

It transpired that he was hugely in debt at the time.

We soon moved to London to a large, damp house in Cadogan Place. Straw had been laid in the street when we arrived to make things quieter for someone dying next door. The sweaty, hearty, red-faced, country squires were replaced by pale, gay, young men who recited poetry and sang to my mother. She was very beautiful, very musical, very sad and lived on cloud nine. A character called Uncle Tommy soon made his appearance and became a permanent member of her entourage. Gradually the pale, gay young men gave way to pale, sad, older men.

Uncle Tommy was a second line politician who did not fight in the war. A tall, ramrod straight creature with Sir Thomas Comyn-Platt. Liked to be known as the mystery man of the Conservative Party. Contested Portsmouth Central in the Election of 1926.

Immensely high, white collars, a bluish nose and a very noisy cuff-link combination which he rattled at me when I made an eating error at mealtime. I dont believe he was very healthy really. Anyway he got knighted for something to do with the Conservative Party and the Nineteen Hundred Club, and Cadogan Place became a rendezvous for people like Lord Willoughby de Broke, Sir Edward Carson, K.C., and Sir Edward Marshall Hall, K.C. I suppose it bubbled with the sort of brilliant conversation into which children these days would be encouraged to join, but, as soon as it started, Grizel and I were sent up to a nursery which had a linoleum floor and a string bag full of apples hanging outside the window during the winter. Grizel, who was two years older than me, became very interested during this period in the shape and form of my private parts; but when after a particularly painful inspection, I claimed my right to see hers too, she covered up sharply and dodged the issue by saying, Well, its a sort of flat arrangement.

The Germans raided London. High in the night sky, I saw a Zeppelin in flames.

One day my mother took me to buy a pair of warm gloves. Some Fokkers came over and everyone rushed into the street to point them out to each other. Then as the possibility of what might be about to drop out of the Fokkers dawned on them they rushed back indoors again.