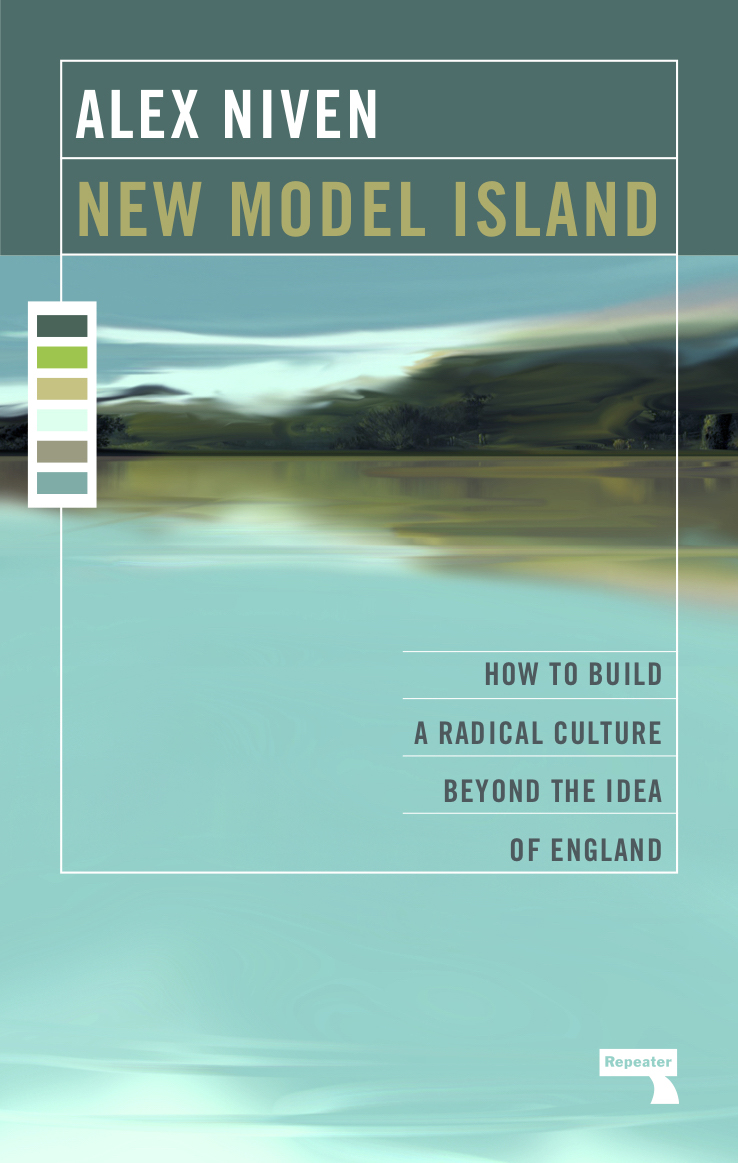

Published by Repeater Books

An imprint of Watkins Media Ltd

Unit 11 Shepperton House

89-93 Shepperton Road

London

N1 3DF

United Kingdom

www.repeaterbooks.com

A Repeater Books paperback original 2019

Distributed in the United States by Random House, Inc., New York.

Copyright Alex Niven 2019

Alex Niven asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

Cover design: Johnny Bull

Typography and typesetting: Frederik Jehle

ISBN: 9781912248254

Ebook ISBN: 9781912248636

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Printed and bound in the United Kingdom by TJ International Ltd

CONTENTS

It was time to start the world again.

My First Picture Bible

FOREWORD

This book is part cultural polemic, part memoir. At its centre is an argument against the narrow Englishness that has dominated twenty-first-century British culture up to this point, and a more hopeful glance forward to the expansive, renovated future that awaits us on the other side of nostalgia for a country that no longer exists. I begin by assuming that England is, at best, a vague anachronism, and at worst, the recent cultural daydream of a neoliberal order which really operates on the basis of finance capitalism, hierarchy, and the denial of more radical popular hopes and dreams.

Put simply, I think we need to abandon England and start looking for a replacement. As well as trying to show up the vanity of recent fulminations about Englishness, and their incompatibility with the twenty-first-century socialist cause, I also try to make a case in what follows for an alternative to the backward-looking, centralising, difference-denying and simply inaccurate clich that England is an island nation ( Martin Amis 2014). In the face of the idea and to a large extent the political reality that our archipelago is a rustic demesne full of quaint towns in the shadow of Fortress London, I suggest that an assertive revival of the late-twentieth-century push for regional devolution, which preceded the retreat into Englishness over the last two decades, must be at the forefront of our contemporary left revival.

Regionalism is a sleeping giant that is now, after a short pause, ready to wake again out of sheer, obvious righteousness. It seems pretty self-evident that a more equal society can only come about on these islands when power is distributed evenly throughout them, as the autocratic relation between London and other areas is levelled down to something approaching parity. For reasons that will become clear, socialist regionalism seems to me a much better and more comprehensive way of achieving this than a retreat into the dimly recalled nationalisms of the Middle Ages, and so this book is fundamentally structured around an argument that seeks to disprove nationalist and advocate regionalist ideals. More than this, it suggests that as the United Kingdom crumbles, we need to completely overhaul the map of the islands, partly in order to avoid the dire consequences of lapsing into hallucinated national Camelots.

To bring home these critical points, I also offer glimpses of related moments in my own narrative of the last few years. The 2010s were a strange, bewildering time a transitional lost decade during which much happened socially and politically, but very little seemed to come to fruition. Like many people, I spent the last ten years trying to work out where on earth the various convulsions, collapses and insurgencies causing alternate hope and despair would lead. Ive tried to give some sense of this turbulent backdrop to recent political thinking and writing in what follows. I wanted to make clear that my portrait of these islands and their culture was shaped not or not only by theoretical musing, but also by certain important encounters in recent years with the people, stories and incidents around me.

This, then, is a book based on lived experience of cultural upheaval. Though I draw loosely on academic texts and ideas throughout, I also try to keep returning to the personal contexts that have shaped my political worldview. This might call for some selective reading of the following text. Readers who want to filter out the personal material are of course free to do so, by focusing on the main essay chapters rather than the lyric digressions on poetry, music and autobiography (though they should be warned that even in the more critically focused sections, first-person narrative creeps in). Similarly, those enticed by the obligatory , to find more tangible political suggestions free from memoir and reflections on recent history.

In spite of the autobiographical element, I hope it is clear that everything here memoir as well as polemic is guided by a desire to affirm a we over an I. This book is an attempt to think through ways in which we can organise ourselves beyond outdated myths and constraining capitalist commonplaces. More deeply, as I hope is clear from the numerous references to my friends, it is written in the knowledge that socialist projects only ever succeed because of the strength, wisdom and solidarity of human collectives. With this in mind, I dedicate this book to my friend Tariq Goddard, and to the memory of my late colleague Mark Fisher.

Newcastle upon Tyne, 2019

PREMONITION

THE BREAKING OF THE SILVER DISH

At the end of the strange, fractious year that was 2016, my first child Oswald was born. Recovering from the experience more than two years later, I dont have very much that is wise or profound to say about it. As many people will know, the arrival of a new child is complicated and arduous enough without any additional pother about What It All Means. But despite the anxiety of the birth and the chaos of its social backdrop (austerity, Trump, political rupture, multiple very public deaths), when it came to deciding on a name, my partner and I felt sure we knew what we were doing. We named our son after the Northumbrian saint Oswald Iding, who in 633 AD returned from exile at the Scottish island monastery of Iona, to found a wide-ranging kingdom in what is now northern England and southern Scotland.

Like most tribal leaders of the time, this historical Oswald was renowned for his military prowess. In assuming the Northumbrian kingship, he defeated a large allied Welsh and Mercian force in the Battle of Heavenfield at a site near Hexham in the Tyne Valley. But Oswald is far better remembered as a spiritual hero. Perhaps his greatest achievement was the foundation of the island monastery of Lindisfarne the cradle of Christianity in the North with the help of an Irish monk, Aidan, who was summoned from Iona to establish a Northumbrian religious centre in the image of its mother institution.

Next page