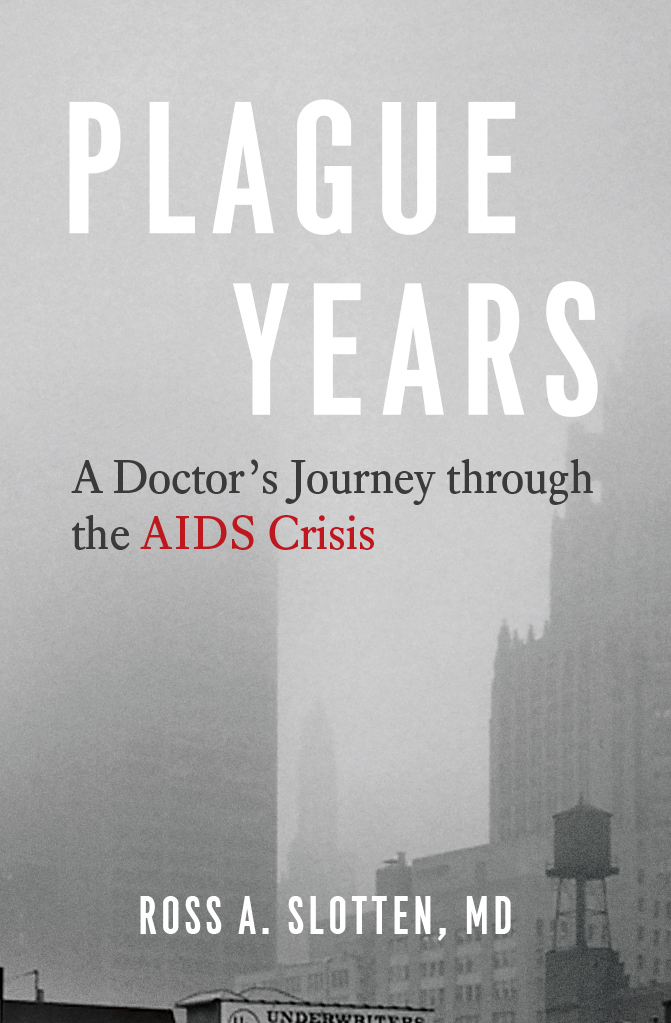

Plague Years

Plague Years

A Doctors Journey through the AIDS Crisis

Ross A. Slotten, MD

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2020 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2020

Printed in the United States of America

29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-71876-7 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-71893-4 (e-book)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226718934.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Slotten, Ross A., author.

Title: Plague years : a doctors journey through the AIDS crisis / Ross A. Slotten.

Description: Chicago : University of Chicago Press, 2020.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020004971 | ISBN 9780226718767 (cloth) | ISBN 9780226718934 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: AIDS (Disease)IllinoisChicago. | AIDS (Disease)

Classification: LCC RA643.84.I3 S568 2020 | DDC 362.19697/9200977311dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020004971

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

To those we lost to the AIDS crisis and to those who survived it

It is a wondrous tale that I have to tell: if I werent one of many people who saw it with their own eyes, I would scarcely have dared to believe it, let alone write it down, even if I had heard it from a completely trustworthy person...

Giovanni Boccaccio, The Decameron

Contents

I was there at the beginning of the AIDS epidemic, and Im still here. I came of age as a doctor and as a gay man during that monumental public health crisis, and thirty-five years later I continue to treat people with or at risk of HIV.

This book is a record of my journey. I kept journals and notes from the first, chronicling the stories of those who died and the few whove survived to the present. Those notes help remind me how and why AIDS ravaged a generation, its impact as catastrophic as that of war and genocide. They also chronicle my own story. My story isnt over yet, and neither is that of AIDS. If we think that it is, were practically inviting it to run rampant once more.

If my narrative ended in 1995, it would add little to the story of the AIDS epidemic. During the bleakest years, from 1981 until the late 1990s, AIDS sparked a creative outburst in the artistic community, whose members were disproportionately annihilated by the disease and were outraged at the indifference of politicians and policymakers. That output began on the margins but came to include influential mainstream plays, memoirs, films, art installations, two Broadway musicals, and even a symphony. A few straight doctors also reported on their experiences, most notably Abraham Verghese in his classic account My Own Country. Once effective treatments became available and the death toll plummeted, a sense of urgency among those afflicted and those who cared for them seemed to dissipate.

But AIDS hasnt disappeared. There is no cure or effective vaccine, so theres no end in sight to one of the worst plagues of modern times. To date, more than seventy-five million people throughout the world have contracted the infection, and thirty-five million have died. Those numbers continue to rise, though no longer at a logarithmic rate. Everyone infected with HIV will carry that virus to their grave, even if what kills them is a heart attack, a stroke, or cancer. But if they stop their lifesaving regimens, known as HAARThighly active antiretroviral therapythen AIDS will kill them first. Imagine the psychological, physical, and financial burdens a twenty-one-year-old man infected with HIV must shoulder for the next sixty years if no cure is discovered! It takes tremendous discipline and willpower to adhere to a daily therapy you cannot miss. Even though we can now control HIV infection, no one wants it any more than they want to lose their limbs, eyesight, or hearing.

This story marks my progress as a doctor who first confronted a challenge for which nothing could have prepared me and who then unexpectedly became an expert. But more important, it marks stages in our understanding of HIV, beginning before anyone had described AIDS, for the conditions that abetted the spread of the disease were present in the decades before its onset. Epidemics happen for a reason. HIV couldnt have gained a foothold and swept across the world, sparing few places, without the ease of international travel; increased sexual promiscuity brought on by the sexual revolution of the 1960s and 1970s; the rapid spread of other sexually transmitted diseases like gonorrhea, chlamydia, syphilis, herpes, human papilloma virus. and hepatitis A, B, and to a lesser degree C; the failure of political leaders to authorize adequate funding to confront the epidemic in its earliest phases; and the disruption of traditional life in many societies by colonialism and civil wars.

The story I tell here is primarily a Chicago story, for New York, San Francisco, and Los Angeles werent the only cities whose gay communities were decimated by AIDS. We suffered too, even if the media overlooked us. Because Im a gay man who treats mainly gay patients, I dont address the epidemics victims who injected intravenous drugs or were infected through contaminated blood products, or women and children, because those stories are beyond my personal experiences. Those stories are eminently worthy of being told, but the ones Ive chosen to tell center on my gay friends and patients. Names and identifying facts have been changed in many instances to protect privacy and maintain confidentiality.

For those who lived through the worst period of the epidemic, this book could bring back memories of an era that we all hope will never be repeated. For those who didnt experience that terrible time, or whove forgotten how terrible it was, let my chapters serve as a warning to the complacent and the ignorant: untreated HIV is as ruthless as any terrorist and as destructive as a nuclear bomb. Humans have never conquered any sexually transmitted disease and are unlikely to do so unless they stop having sex. Perhaps HIV will someday become a historical footnote if the infection can be cured or a preventive vaccine is developed, but it wont vanish, just as other sexually transmitted diseases defy eradication despite the earnest efforts of public health officials and medical practitioners. HIV will remain a part of the human landscape for a long time to come.

Its been a privilege for me to travel on this journey with my patients, some of whom have managed to stick with me for more than three decades as the management of their health has evolved and improved dramatically. I hope our collective and separate journeys through a kind of holocaust are worth remembering on their own, and for the lessons they might yet teach.

No End in Sight (1992)

To the casual visitor, the west wing of the eleventh floor of St. Joseph Hospital didnt look like a vision of hell. The elevator opened into the solarium, a glass-encased semicircular space with a panoramic view of Lincoln Park and Lake Michigan. In the distance sailboats plied the waters beyond a steady stream of traffic on Lake Shore Drive; in the foreground there were joggers on tree-shaded paths. Northward, fashionable high-rises lined the park; to the south rose the iconic skyscrapers of downtown Chicago. What wasnt visible, to the west, was Boys Town, the citys gayest neighborhood, a jumble of bars, restaurants, sex shops, and inexpensive apartmentsthe epicenter of the AIDS epidemic in Chicago. It was September 1992, and the city brimmed with life, in stark contrast to 11 Westour AIDS unitwhere death reigned.

Next page